This new year, I would like to begin the Christ-Animated Learning Blog by presenting a four-part series about some advanced skills necessary for Christ-animating learning. Today, I begin by discussing one advanced skill that I think should be a major component of advanced forms of Christ-Animated learning, yet I rarely see it. For example, in the six years of editing this blog, I can only recall a dozen or so posts on this topic. I am talking about the Christian analysis of academic theories.

Every major academic discipline is shaped by and primarily composed of theories. In fact, the Oxford English Dictionary defines theory as “The conceptual basis of a subject or area of study. Contrasted with practice.” The conceptual basis is a set of “abstract knowledge or principles.” More specifically, academic theory is usually “an explanation of a phenomenon arrived at through examination and contemplation of the relevant facts; a statement of one or more laws or principles which are generally held as describing an essential property of something.” Think of critical theory or symbolic interaction theory.

Now, theories can function in three ways. At one level, they can simply attempt to be descriptive. They tell us how the world works (e.g., quantum theory).

Second, they can be used as predictive tools. Academics tend to love this one. After all, if we have predictive power about how the world works, we can try new things knowing that a particular result will be achieved. We can send a person to the moon or Mars. We can also make moral claims about how the world does and should work. Furthermore, we can avoid mistakes. If certain economic theories have greater predictive power than those of Karl Marx, we can predict what economic policies may succeed or fail. These predictive theories, when proven accurate and replicable, give us the power to claim that we are promoting the appropriate policy or approach to human flourishing or problem-solving (although they always need empirical testing). They can guide our actions and professional practice.

Finally, there are normative theories (e.g., feminist theories). These theories do not simply explain the world as it is, but propose particular normative goals and ways of achieving them. Christian theory, which originates from Christian theology, should function at all three levels. It should also be used to analyze other theories.

Analyzing Theory Christianly

One of the advanced skills every Christian academic should learn concerning Christ-animated learning is how to evaluate theories within their discipline Christianly. Now, this skill cannot be developed simply by taking Bible verses and citing them without thinking theologically. Citing Bible verses is what the Pharisees were good at doing.

Mark 10:2-8 provides a good example of the clash between those focusing just on a particular verse from scripture versus what Christ teaches us to do—to think theologically about various dimensions of life.

Some Pharisees came and tested him by asking, “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife?” “What did Moses command you?” he replied. They said, “Moses permitted a man to write a certificate of divorce and send her away.” “It was because your hearts were hard that Moses wrote you this law,” Jesus replied. “But at the beginning of creation God ‘made them male and female.’ ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.’ So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.”

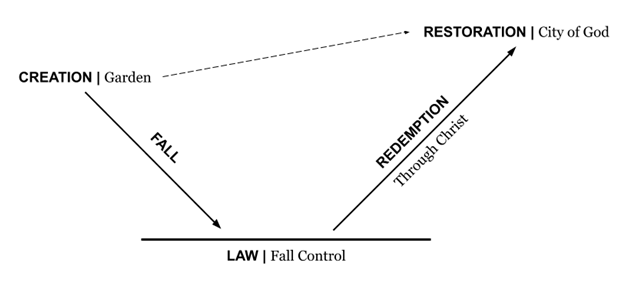

Here we see Christ demonstrating how to think about reality both theologically and teleologically. First, Christ noted that the question concerned Fall control, but it failed to look at the original ideal for marriage that God set forth in creation. If we are going to think about an area of life, we should focus on God’s highest ideals for it, whether revealed through creation or redemption, and not Fall control.

Second, Christ was quite clear that both the law and marriage needed to be analyzed teleologically—taking into account God’s purpose for both. For example, he pointed out what I also teach students about student conduct codes—laws or rules are not our highest moral ideals. They exist due to sin and are meant to restrain sin (i.e., fall control).

Second, Christ was quite clear that both the law and marriage needed to be analyzed teleologically—taking into account God’s purpose for both. For example, he pointed out what I also teach students about student conduct codes—laws or rules are not our highest moral ideals. They exist due to sin and are meant to restrain sin (i.e., fall control).

If Christian scholars are to analyze any dimension of reality or help others do so, they must place that dimension and the associated theories for understanding it within the various dimensions of God’s story and take God’s purposes into account. Here are four questions, and some associated sub-questions, I usually use when evaluating an academic theory.

1. What about this theory reflects God’s purposes established in creation?

a) How does it conceptualize human persons and the purpose of humanity? How is that consistent or inconsistent with a Christian view?

b) Does it accurately describe the God-ordained or revealed purpose of a particular social institution (e.g., marriage, education, law, etc)?

c) What creation-based end or ends does it seek to accomplish?

2. What is fallen or reductionistic about this theory?

3. How can one draw upon Christ and what the New Testament teaches us to redeem the theory (i.e., reverse its fallenness), if it can or should be redeemed?

4. How might this theory need to change in light of the Kingdom of God?

All of these questions are important. For example, I can recall a nephew of mine being frustrated with how critical theory was presented in his class at a Christian university because the presentation only emphasized how critical theory can advance justice without considering these other questions (e.g., how might critical theory be fallen?). I told him that he was right to be frustrated because he was not receiving a full Christian education regarding the theory. He was also not being taught Christian critical thinking—which actually is best described as creative, critical, and redemptive thinking and not simply critical thinking (which tends to focus on what is fallen about a reality, group, identity, theory, institution, etc.).

An Example from My Academic Field: Moral Development

As with any area of Christ-animated learning, we need to look at specific examples to see how this approach can be utilized. The first step is always to represent the theory accurately and not provide students with a simplistic caricature of it. Thus, it is usually helpful to ask students to read the original source of the theory instead of a second-hand textbook author’s description of the theory. In my moral development class, for example, I make sure students read Lawrence Kohlberg’s original presentation of his theory of moral development.1

So, what does Kohlberg’s theory of moral development help us understand about God’s good creation? Well, God designed us to go through developmental stages not only when it comes to general growth but also in how we reason about moral issues. Thus, when I asked my kindergarten-aged son a few decades ago how his day was, and he replied, “Great, I did not get a color change” [the stop-light disciplinary method used by the teacher], I was not surprised. From my knowledge of Kohlberg, I knew my son was reasoning at moral stage one, “the punishment and obedience orientation.” Interestingly, I recently had dinner with Kohlberg’s son, and he mentioned that he thought it problematic that his father skipped this stage with him.

What might be fallen or reductive about Kohlberg’s theory? Here, I have lots of things to say in class, but in this essay, I will only focus on a couple of critiques. First, we find that Kohlberg takes a reductive approach to the human person (as do many academic theories). He largely conceives of the human person as a rational actor. As Christians, we should be concerned with moral reasoning but also with moral affections and actions. That’s why one of the best definitions of character education is teaching students to know the good, love the good, and do the good. Kohlberg’s theory largely focuses on knowing and reasoning about the good.

Second, we find that Kohlberg takes a reductive approach to the moral life. As I recently discussed in a journal article and a recent book, much of the moral life does not involve figuring out how to resolve a conflict between two moral principles. Instead, it involves overcoming moral challenges on our way to being excellent as a human being and excellent within various sub-identities (e.g., an excellent neighbor, friend, spouse, parent, citizen, professional, etc.). We overcome moral challenges differently from how we resolve moral dilemmas. That process requires the development of virtues and practices and not simply advanced forms of moral reasoning.

How can Kohlberg’s theory be redeemed, if it should be? Here, I introduce students to Christian ways of thinking in a more complex manner, exploring moral development and moral dilemmas. One of the points I highlight is how Kohlberg’s theory is primarily intended to address what it means to be a good citizen. That’s why it ends with a universal principle of orientation toward justice (the major virtue guiding political communities).

The problem is that for Christians, our primary community of focus is the Kingdom of God. Thus, we are to be oriented toward God and the primary virtues by which we and our Christian communities are analyzed, such as faithfulness (see, for example, how God judges the churches in Revelation 2-3), love (Mt. 25:32-46), etc. Thus, we will approach the virtues we use to evaluate ourselves and a moral community differently.

For instance, one of the questions I often ask my student affairs students is whether Baylor should permit having a Muslim Student Group on campus. Of course, Kohlberg’s theory would lead one to show justice to different religious groups—what one would expect at a public university. At a Christian university, however, we prioritize faithfulness toward the triune God (a virtue not mentioned by Kohlberg). Now, faithfulness does not mean exclusion. Christians seek to welcome the stranger. But this hospitality is guided by our meta-moral principle of love for God and our meta virtues such as faithfulness (for more see here, here, here, and here).

Similar to this evaluation, I would like to see more Christian scholars demonstrate how they evaluate dominant theories in their discipline Christianly (and perhaps submit some blog examples of this type of evaluation). It is certainly an advanced skill every Christian professor should teach students.

Spot on! Shared Family Theory at graduate level for the last 50 years. Wish I had your article over all that time.

Thank you, Perry, well said! I quote Sherlock Holmes to my students: “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

Humans are compulsive theory makers. As Christians, the “testing of all things” is built into our theology as vassal rulers of what God has entrusted to us, even and especially in our intellectual domain.

A relevant challenge indeed. *And, how are professors, pastors, and small group leaders persuading others with an array of faith theories without examining their own understanding of their faith and its history as thoroughly as they should? We’ve seen this dilemma split entire denominations, so it is reasonable to suggest it is an issue.