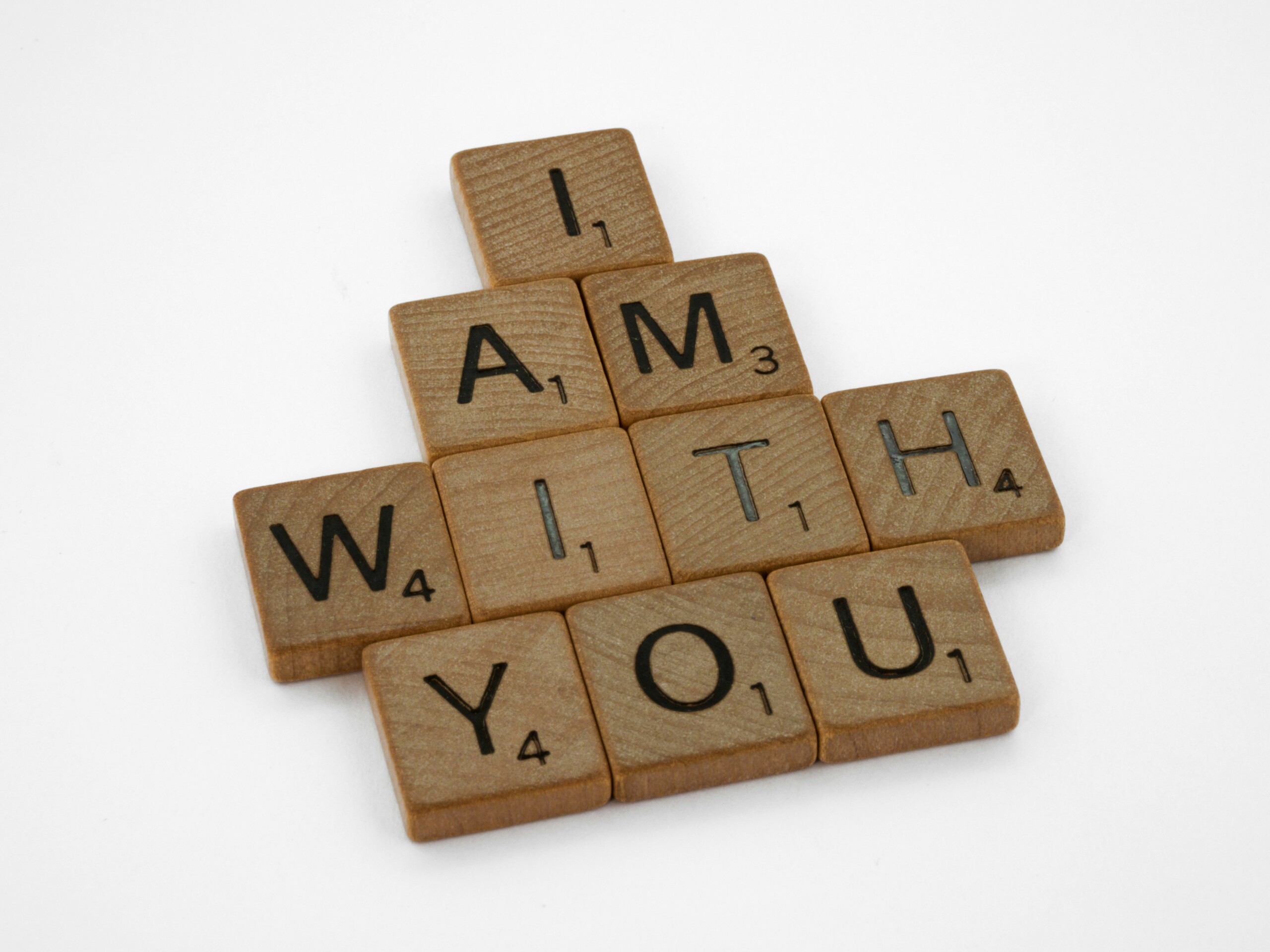

During my sabbatical in the winter quarter of 2025, I had the opportunity to begin a Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) program through the Spiritual Care Department at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington. In our first week of orientation, our CPE supervisor offered a definition of spiritual care that has stayed with me more than any other: with-ing. It is the sacred practice of being fully present with the people right in front of us.

As I began to understand what it means to serve as a chaplain in a Level 1 trauma center, I asked one of the Harborview chaplains on staff what kept him coming back. Without hesitation, he said, “It keeps me soft, grounded, and tender.” Over time, I’ve come to see how this place has done the same for me— inviting me also to become softer, grounded, and tender.

What’s become clear is the deep connection between the work of chaplaincy at Harborview and the work we do as professors in the classroom. In this challenging time for higher education marked by much uncertainty, many of us have been called to reimagine and recommit to our own version of “with-ing”—with our students, with one another, and with ourselves.

I see many parallels between chaplaincy and teaching, as both are grounded in presence, empathy, and relationship-building. Presence is the connective tissue serving as one of the most powerful forms of care across all vocations. As I’ve stepped into the chaplain’s role, I’ve been grateful for the opportunity to deepen practices of active listening, bearing witness, staying grounded in the here and now, and holding others with respect and compassion.

Kerry Egan, in her book On Living, writes that chaplaincy is less about storytelling and more about “story-holding”—and I couldn’t agree more. “We listen to the stories that people believe have shaped their lives. We listen to the stories people choose to tell, and the meaning they make of those stories.”1 In this last year working at the hospital, I’ve had the privilege of holding countless sacred stories of love and loss and of suffering and resilience.

Teaching as Story-Holding

The classroom, too, is a space filled with stories. Our work as educators is to build rapport for our students to feel seen and heard and to create environments where students can connect with one another and the material—and feel safe enough to share their stories. When we foster trust and openness, we give students the space to explore their identities, confront challenges, and give voice to their lived experiences. In doing so, we not only support their personal growth but also deepen their capacity to learn.

J.S. Park, a hospital chaplain and writer, describes chaplaincy as the role of a “grief catcher.”2 In recent visits in the hospital, I have understood the sacredness of this role as patients and families have shared raw, unfiltered emotions: the father wondering if he failed his son, the woman grieving the dog who maimed her, the woman questioning her own belovedness. There is something deeply human about simply bearing witness to someone’s pain and letting them know they are not alone.

Teaching, too, is a form of catching—catching questions, frustration, fear, grief, and even transformation. These are the moments we rarely plan for in our syllabi, but they are often the most meaningful. Whether a student navigating a family crisis asks for grace or one is struggling with confidence in finding their voice, we as teachers have the opportunity to respond—not always with answers or quick fixes, but with presence, attention, and care. We hold space for them to connect the dots and to make meaning. We offer ourselves.

Witnessing Sacred Transformation

In both chaplaincy and teaching, witnessing transformation in others is a sacred privilege. We accompany people as they confront painful truths, wrestle with questions of identity and meaning, and begin to reframe their stories. It’s powerful to be able to be a part of someone’s journey and to bear witness when the ground is shifting under their feet through seasons of suffering and awakening.

And in both the hospital and the classroom, even in the hardest circumstances, moments of joy can break through. These glimmers play a vital role in the work of healing, wellness, and justice—both individually and collectively. In Unearthing Joy, a follow-up to her groundbreaking book Cultivating Genius, Dr. Gholdy Muhammad introduces joy as the fifth core pursuit in her instructional model. She argues that teaching grounded in cultural and historical realities must cultivate joy, identity, intellect, skills, and criticality. Her vision resonates not just in education but also in spiritual care. Both chaplains and educators are called to create joyful, inclusive spaces that affirm identity, promote critical thinking, and honor self-expression.

Learning to Talk Less and Listen More

In teaching, “wait time” is often a secret weapon for deepening critical thinking and metacognition. We learn to pause intentionally after asking a question, knowing that even a few seconds of silence can dramatically improve the quality of students’ responses. This is easier said than done because silence can be uncomfortable, yet research shows that these pauses create space for students to make their own connections rather than relying on us to rescue them with quick answers that can short-circuit their thinking.

In much the same way, “wait time” can be an important part of the healing process in a hospital room. Rather than jumping in with platitudes, we learn to sit with patients in their disappointment, fear, and loneliness. By saying less, we create room for them to find meaning in their own story. Listening with love, humility, curiosity, and hope can be a profound form of care.

Holy Mutuality

Holding both roles as chaplain and professor has reminded me of a core theological truth: we belong to one another. We are bound in a holy ecosystem of interdependence. There is a beautiful mutuality in this work—whether we are standing at the bedside or standing in front of the classroom. When we hold the stories of others with tenderness and reverence, we too can be changed.

God’s desire for us is holistic flourishing, and through roles like chaplaincy and teaching, we get to participate in the redemptive work of healing. In both spaces, we enter into others’ brokenness not as fixers, but as faithful companions. As Tish Harrison Warren writes in Liturgy of the Ordinary, “Our task is not to somehow inject God into our work but to join God in the work He is already doing in and through our vocational lives.”3 Whether in a hospital room or a classroom, we are invited to join God in the holy work of presence, listening, and transformation.

We have the privilege of sacred encounters every day. We are called to the art of “with-ing” in our work with all kinds of people we encounter through our days, and to respond with a spirit that is soft, grounded, and tender. And truly, that is what the world needs more of right now.

“Our task is not to somehow inject God into our work but to join God in the work He is already doing in and through our vocational lives.” Thank you for this reminder.

Emily, such a great reminder–and sorely needed in a society pressured to operate at warp speed day and night. Thank you for this. *I am a former school principal, and sadly, one of my teachers told me one time way back when that she knew she had about 10 seconds of my attention, and then she could see my mind moving on to the next task…

Thank you for this profound post and its reminders of profoundly simple truths not only for teaching but for “with-ing,” which can be the same thing as being a disciple and being a friend. I think this is my favorite Christian Scholars post ever, and the most immediately applicable to every aspect of my life.

Thank you so much for this generous and thoughtful response. If the piece invites us into deeper presence with God and with one another, then I’m thankful it’s doing the work I hoped it might. I’m honored that you found it so immediately applicable, and I really appreciate you taking the time to say so.