The survivors of the first atomic bomb used in war, which was dropped in Hiroshima, have been telling their survival stories for many decades. Many of them have found that telling their experiences is empowering, as it gives them a purpose to live and allows them to share their knowledge worldwide with people of all generations. However, as they age, many survivors are increasingly concerned that there will be no one to tell future generations about their experiences. Akiyo M. Cantrell proposes that Christians ought to respond to their concerns positively by learning the survivors’ stories, from the survivors’ perspectives, and telling the stories to others, while keeping the survivors in their prayers. Ms. Cantrell is a lecturer at University of California, Santa Barbara.

Introduction

“I’m from Hiroshima.” When people hear my answer to their question, “Where in Japan are you from?” they sometimes respond to my answer with “Wow,” “Oh,” or even “I’m sorry” which many other places in Japan would not probably elicit. These responses, along with the expressions on their faces, suggest to me that they acknowledge the place as more than the name of a city. It is the Hiroshima, one of the two places that experienced the only atomic bombing in human history. The year 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of Hiroshima. The city of Hiroshima has been the Hiroshima in people’s memory for three generations.

Remembering Hiroshima has always been a part of my life. It is the place where I was born and grew up. Listening to the survivors’ experiences in school, reading books about them, and witnessing Hiroshima recover from its traumatic past have played a crucial part in shaping my identity. One of the survivors’ narratives that I heard was my own father’s. That fateful day, amid the chaos, he was told to help people being evacuated from the city at a train station after the bomb had been dropped. He described to his children and later to his grandchildren the horror he witnessed and experienced: “People were in agony. Their skin was hanging down from their arms. I could not help them very much. I had to run away from the site soon afterward, because I could not stand what I saw.”1

These fragments of painful memory have been passed down from one generation to another, starting from those who actually experienced or witnessed the bombing. As survivors have retold their stories to various audiences in many locations, their memory has also become that of larger, public communities.

The scholarly community, especially in North America, has shown only moderate interest in survivor accounts from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.2 While John Hersey’s Hiroshima gave American readers the chance to know the sufferings of victims there within a year of the war’s end, sustained interest on the part of the American public or American academics has been hard to come by, especially in comparison with the level of attention garnered by Holocaust survivor testimonies.3 My purpose here is not to review the scholarship on atomic bomb survivors but instead to familiarize Christian Scholar’s Review readers in an introductory way with some of the central themes that come through the simple but poignant testimonies of hibakusha. Literally translated, hibakusha means “explosion-affected person(s),” a coined word to refer to the atomic bomb survivors.4 Commenting on the group, UNODA, the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, identifies hibakusha who tell their survival stories as “shining examples of turning their personal tragedies into a struggle to promote peace and to create a world free of nuclear weapons.”5 However, with 70 years having passed since the atomic bombing, the numbers of those shining examples are declining. Therefore, their advancing years makes it worth asking, who will be the keepers of their memory when they have passed? Might Christians have an ethical responsibility to preserve their witness? In the sections below I will describe the formation of a communal memory of Hiroshima through three essential stages: experience; transformation of identity; and passing the memory across time and place. The narratives of Hiroshima survivors in this paper are those of the registered volunteer storytellers of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and were collected for a sociocultural linguistic study in late 2002 and early 2003.6 The storytellers typically convey their survival stories to various groups of museum visitors, such as elementary school students, college students and foreign visitors. Their format is always a lecture style: 40 to 50 minutes of descriptions of their experiences of the war, the atomic bombing, and their lives after the destruction, followed by 10 minutes of questions and discussion with the audience. The survivors share their stories in the museum’s lecture hall. Although they speak in the museum, the storytellers do not receive any training in public speaking from that institution and they are free to say what they wish. In addition to the storyteller narratives recorded at the museum, I will also analyze examples from interviews I conducted with several of the storytellers. In the excerpts provided, I include both the original Japanese and my English translations.

Although each storyteller describes the moment of the bombing and the suffering that ensued in their own ways and their descriptions are never identical, those horrific experiences of August 6, 1945 and the days immediately following commonly form the heart of their survival narratives. Here then the construction of the communal memory of Hiroshima begins with the raw experience of those who were there.

Stage One: Experience

One aspect of the moment of the bombing that the storytellers typically illustrate is how powerful the blast was. One storyteller, Tanaka,7 who was an early teenager at the time, describes the moment using onomatopoeia:8

(1) Tanaka

1. kyu=ni watashitachi no XXXippaini hikari ga ne, 2. bua===== tto hirogaru. (1-2) ‘Suddenly light spread all over the XXX like bua=====’

The onomatopoeia bua===== pictures how instantly and completely the city was surrounded by the massive energy of the light from the atomic bomb. He also uses memetic words, which are a very common linguistic tool for Japanese speakers to express the vividness of the scene they are describing. With the expression of do=====n “boom” Tanaka depicts the shock of the blast:9

(2) Tanaka

1. do=====n tto kita.

‘(The shock) came, boom!’

2. de,

‘then’

3. sono,

‘(At) that (time)’

4. do====n tto kita toki ni,

‘When (the shock) came like boom’

5. karada ga guraguraguragura tto shita no o oboetoru.

‘I remember my body shook like guraguraguragura’

In the same segment above, the mimetic word do=====n is followed by another mimetic expression whose dictionary form is guragura (“waggle”). The repetition of the word guraguraguragura in line 5 illustrates how strong the shock of the explosion was.

After narrating this fateful moment the survivors usually tell what happened to themselves or what they witnessed. In the example below, Yamada, a female storyteller, vividly talks about the severe injuries she received to her face, neck and hands.10 The bombing caused these parts of her body to be disfigured:

(3) Yamada

1. te mo igandemashita.

‘(My) hands were misshapen’

2. ahiru mitaini,

‘Like ducks’

3. kokoe,

4. maku hattemashita.

(3, 4) ‘(They) were webbed with thin skin here’

5. ahiru tte wakaru ne?

‘(You) know ducks, (right)?’

6. maku hatterujyaro?

‘(Their feet) are webbed with thin skin, right?’

7. jyake yubi ga ippon ippon,

8. katachi o nashitenakatta te ga.

(7, 8) ‘(Just like ducks’ feet) each of (my) fingers (lost its shape) (lit. did not form its shape)’

9. yakedo de makka deshita.

‘(My fingers) were very red because of burns’

10. kao mo kubi ga konnannattamama me wa sagattoru me wa,

‘(Regarding my) face, (my) neck stayed like this, (and my) eyes were (lower than where they were supposed to be)’

((YAMADA TILTS HER NECK AND PUTS IT ON HER SHOULDER))11. hana ga sagattoruyo=na jyo=tai de,

‘(My) nose was lower (than where it was supposed to be)’12. kocchigawa wa dandandandan,

13. XXX desu ne?

(12, 13) ‘This side was gradually XXX, you know?’

Yamada continues to talk about what happened to herself, including her hard life after the bombing. As she tells her story to a group of sixth graders, Yamada describes how people used to ridicule her harshly:11

(4) Yamada

1. zenshin yakedo o shita Yamada-san o mita,

2. hitobito wa,

(1-2) ‘People who saw Mrs. Yamada (that is, me) whose body was all burned (said)’

3. omae genbaku jyaro=.

‘“You (experienced the) A-bomb, didn’t you?”’

4. utsuru.

‘“(You’re) contagious”’

5. densenbyo= jya.

‘“(You’re) an epidemic”’

6. kore ijime dattan da yo.

‘This was bullying’

7. utsuru.

8. densenbyo= to iwaremashita.

(7, 8) ‘I was told that I was contagious and an epidemic’

9. ima dekoso,

‘Now’

10. genbakusho= toiu namae ga tsuitemasu.

‘(Physical damage from the atomic bomb) has a name, genbakusho (atomic bomb disease)’

11. to=ji wa?

‘At that time’

12. Yamada-san makkana kao o shite,

‘Mrs. Yamada (that is, I) had a very red face and’

13. makkana te o shite kubi ga igande,

‘Very red hands, and (my) neck was not straight, and’

14. ko= hyokohyoko aruitetara oma- omae ge- genbaku jyaro= ga.

‘when I was limping, (people said,) “You (experienced the) A-bomb, didn’t you?”’

15. utsuru de.

‘ “(You’re) contagious”’

16. ijimeraretan desu.

‘I was bullied’

17. kore wa senso= no ijime desu yo.

‘This is the bullying of war’

Combined with the additional reality that she and her family could not afford surgery to repair her appearance, the bullying and stigma from the local community not only made her suffer but filled her with bitterness and hatred. She describes her emotion at that time:12

(5) Yamada

1. soshitara,

‘But (lit. and then)’

2. Yamada san wa,

3. shu=tsu o suru.

4. okane ga arimasen.

(2-4) ‘I (lit. Mrs. Yamada) did not have money to have an operation’

5. kokode mondai desu.

‘(It was) a problem’

6. yononaka o nikumimashita.

‘I hated society/the world’

7. senso= o noroimashita.

‘I cursed the war’

Moreover, the agony was not just hers but her mother’s as well. Her testimony relates the anguished cry of her mother to American soldiers in Japan after the war had ended.

(6) Mrs. Yamada

1. shinchu=shitekita Amerika gun ga haittekitara,

‘When the American military (who came to Japan after the war) came (to Hiroshima)’

2. watashino oka=san wa ne=,

3. atashino musume o moto e kaeshitekudasai.

(2, 3) ‘My mother (used to say), “Please give back to my daughter (her) original (appearance)!”’

4. nihongo de gaijinni yutteta.

‘(She) used to say (this) to foreigners (that is, military personnel) in Japanese’

Note that Yamada mentions that her mother was imploring the American soldiers in Japanese. Soldiers who are sent to an occupied territory do not usually speak the language of the occupied land. Likewise, people in the occupied land do not normally speak the language of those with whom they fought.13 Yet, the difference in languages did not matter to Yamada’s mother. The suffering and agony of having her daughter severely disfigured and being too helpless to save her moved her to plead with the U.S. soldiers in Japanese.

The physical and emotional suffering caused by the bombing is also mentioned in the narrative of Matsuda, another storyteller. As he tells his story to a group of Turkish visitors, he mentions how he felt about the burns that he had on his arms:14

(7) Matsuda

1. sorekara hachigatsu desu kara=,

‘Also, since it (was) August (when the bomb was dropped)’2. ano=,

‘Uhm’

3. byo=in kara kaette.

‘(When I) came back from the hospital (that I had gone to with my grandmother earlier that morning)’

4. mazu,

‘First’

5. uwagi o nuide,

‘(I) took off (my) jacket, and’

6. hansode no shatsu ni hanzubon.

‘(I was wearing) a short-sleeved shirt and shorts’

7. ne?

‘You know?’

8. natsu desu.

‘It (was) summer’9. hansode no shatsu ni hanzubon.

‘(I was wearing) a short-sleeved shirt and shorts’

10. ima no pika===tto hikatta,

11. nessen niyotte,

(10, 11) ‘Because of the heat ray that flashed (like) pika=== (that I have just told you about) now’

12. kono ude.

13. hiji.

14. ryo=hiji ne?

15. yakedo o shiteorimashita.

(12-15) ‘I burned this arm, (my) elbows, both of them, you know?’

16. e=,

‘Uhm’

17. ima mo yakedo no ato ko= tsuiteorimasukeredomo,‘(I) still have scars from the burns like this’

18. sono go no gakuse=se=katsu,

19. shakai se=katsu nioite,

(18, 19) ‘After that (that is, getting burned by the bombing), (when I was) a student (and then I started) working (lit. during my life of being a student and a worker)’

20. watashi wa kono yakedo o hito ni mirareruno taihen iyadatta.

‘I really didn’t like to have my burn injuries seen by (other) people’

21. hazukashikatta desu.

‘(I) was embarrassed’

22. kanashikatta desu.

‘(I) was sad’

23. kuyashikatta desu.

‘(I) was upset/angry’

As Yamada was stigmatized by society, so Matsuda felt rejected by it because of his burn injury. People were aware that he looked different, and that made him feel “embarrased, sad, and upset/angry” (lines 21-23). Like most Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors, these two make clear that their wounds were social and emotional, not simply physical.

While the lives of those who were victimized by the atomic bomb were significantly shaped by that experience and their personal histories cannot be told without it, their stories do not end there. Instead, the survivors who testify at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum go on to explain the transformation of their identity from victims to ambassadors of peace.

Stage Two: Transformation of Identity

Christians know it is God’s forgiveness that releases them from their old sinful selves. It is also forgiveness that sets Hiroshima survivors free from hatred. Kato, one of the storytellers at the museum, described her experience of forgiveness to me during an interview. She explained to me how hard her life had been after the war.15 That hardship made her increasingly bitter toward the United States. But one day her negative emotional state was radically transformed through an encounter with an American visitor to the museum:16

(8) Kato

Telling an interviewer about her life after the war,

1. honttoni sono go no seikatsu ga,

2. taihen de,

(1, 2)‘(My) life after the bombing was really hard, and’

3. watashi wa=,

4. zettai amerika o uramukara ne.

(3, 4) ‘I (was always saying,) “I absolutely hate America”’

5. watashi wa zettai chichi o,

6. totta amerika o uramukara ne.

(5, 6) ‘“I absolutely hate America which took my father”’

7. i==ssho= watashi wa amerika o uramukara ne yu=te zutto yu=teta.

“I will hate America for the rest of my life”’

8. dakedo,

‘But’

9. itsuka ne?

‘one day’

10. Amerika no hito toka ironna gaikoku no hito no sho=gen shita koto ga arun desu.

‘I told (my experience of the bombing) to American people and people from various foreign countries’

11. sono tokini amerika o uramimasu ka= yu=te yuwareta kara ne,

‘At that time, when (an American) asked me, “Do you hate America?”’

12. (H) bua===tto mune ga tsukaete ne?

‘I became (very) emotional (lit. (My) heart got stacked like bua===)’

13. uramimashita.

‘(I said,) “(I) hated (America)”’

14. dakedo ima ne?

‘“But now”’

15. anata no kao mite yamemasu yu=te watashi yuttandakedo,

‘I said, “(I) see your face and (I) stopped (hating) (lit. I quit hating looking at your face)”’

16. gomennasa=i yutte te o nigicchattan yo ano=,

17. otoko no=,

18. gakuse=san ga.

(16-18) ‘The (American) male student said, “I’m sorry!” and held my hand’

19. gomennasa=i yu=te te o nigichatta kara ne,

‘Since (he) held (my) hand saying, “I’m sorry!”’

20. mo= ima,

‘(I said,) “Now”’

21. ima kokode watashi fukkirimasu yu=te yu=tan dakedo,

‘“I will let go of (my hatred) right here,” but’

22. honttoni uramimashita yu=tan.

‘(I said,) “I really hated (America)”’

For Kato, this moving interaction with an American student was a moment of forgiveness. The transformation of her negative emotion was evoked by the man’s apology. According to her description of this conversation, the apology was altogether sincere. In line 19, she mentions not only his utterance but the gesture that accompanied it, ‘…(he) held (my) hand saying, “I’m sorry!”’ This apology was immediately followed by Ms. Kato’s forgiveness toward America. She clearly says in lines 20 and 21 (‘I will let go of (my hatred) right here…,’) as well as lines 13 through 15 (‘(I said,) “(I) hated (America)”: ‘I said, “(I) see your face and (I) stopped (hating) (lit. I quit hating looking at your face)”’) that she forgives America.

Such stories of dramatic and immediate shifts toward forgiveness typify some but certainly not all survivor accounts. Others bore the bitterness and hatred that naturally arose from the suffering of their families, neighbors, and city for decades before finding some greater measure of peace with the perpetrators. More broadly, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki collectively needed to confront their bitterness and consider how they would define themselves in the post-World War Two world. Would their identities forever be limited to the status of victims of unspeakable devastation? Or would they be able to reinvent themselves to fulfill some other role? Remarkably, in both cases, these communities since the 1950s have dedicated themselves to being ambassadors of peace and staunch advocates for an end to the use of nuclear weapons.17

Similarly, the transformation of individual atomic bomb survivors has not usually stopped with forgiveness. Hoping to be reconciled with their fate after the war and bombing, many have been led to find a mission in their lives to redeem their terrible experience. Some find it as museum storytellers. Why do they tell their stories to others? Very simply, they want to tell people how important peace is. Hayashi, for instance, identifies this new role as his mission:18

(10) Hayashi

1. dakara maa,

so uhm

2. sore ga.

it SBJ

3. aredake takusano hito ga,

4. hisanna shinikata shita n dakara honto=.

(1-4) ‘So, uhm, since so many people died in a horrible way. Really,’

5. ma moushiwakenai youna.

6. kimochi mo arimasu kedo ne?

(5, 6) ‘I feel guilty (about living)’

7. dakara sono hanmen yappari.

‘So, on the other hand, that’s why’

8. ja=,

9. mitekita koto o.

10. tsutaenaito [ikenai] na to,

(8-10) ‘(I think that) I have to pass on what I saw (to other people)’

11. souyu= shimei o takusaretanjya nai ka ttoiu,

12. koto o?

13. ma=.

well

14. ma omou wake desu yo ne=.

(11-14) ‘I think that I have that mission assigned to me’

Notice that Hayashi mentions his guilt in this example (lines 3 through 6). It is guilt that he somehow managed to survive the bombing when others did not. This is an attitude very common among hibakusha. Survival is a burden in the face of such massive loss. Survivors feel the weight of having “to live” for those who perished. One might wonder, then, why Hayashi chooses to tell his survival story publicly while he feels guilty about the fact that he is still alive. The guilt about his survival and choosing to tell his story are not, however, necessarily contradictory. In fact, he chooses to tell his story because he feels guilty. This is indicated in his use of the conjunction dakara “so” in line 7, which connects his mention of his survival guilt (lines 3 through 6) and his thought about what to do with his experience about the war and the bombing (lines 8 through 10). The verb phrase, tsutaenaitoikenai “(I) have to tell” in line 10 clearly indicates how his guilt about survival makes him view his storytelling: He sees it as his obligation because he is still alive (lines 9 and 10). Yet, it is more than that. He identifies telling others his experience as his mission (lines 11 through 14). It gives him purpose and a means of responding to the two dominant realities of his life: experiencing an atomic bombing and surviving it. Becoming an ambassador of peace has allowed him and many other Hiroshima survivors to reconcile themselves with their horrific pasts and their ongoing existence.

Stage Three: Passing Down the Memory Across Time and Place

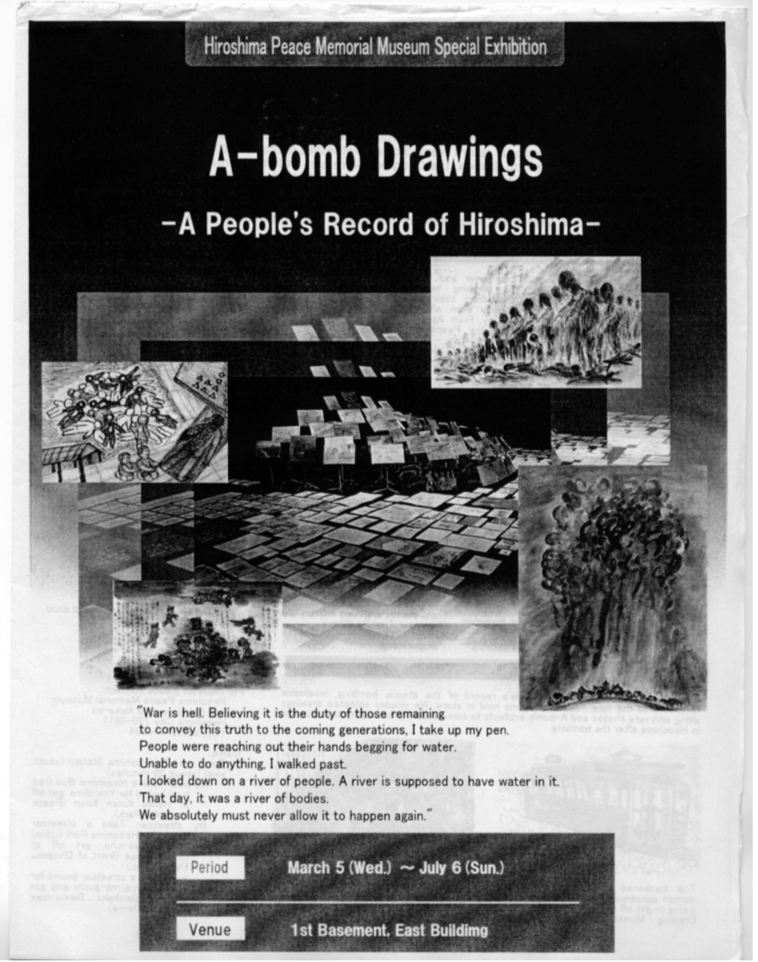

The memory of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima is conveyed not only in the narratives told by the survivors but in various other forms, such as film, art, adult and children’s literature, memoirs and oral history interviews, museum displays, memorial parks, annual commemorations, and music. For example, while I was collecting narratives from the storytellers at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2003, the museum was exhibiting its collection of drawings created by atomic bomb survivors. The flier in Figure 1 captures the new identity of Hiroshima survivors. It quotes a message submitted by one survivor who sent his/her drawing to the museum for the exhibition:19

War is hell. Believing it is the duty of those remaining to convey this truth to the coming generations, I take up my pen. People were reaching out their hands begging for water. Unable to do anything, I walked past. I looked down on a river of people. A river is supposed to have water in it. That day, it was a river of bodies. We absolutely must never allow it to happen again.

Figure 1: Flier of Exhibition of Drawings from Hiroshima Survivors (English Version, Front Page)

Note that the message asserts that telling the horrible experience they had to other people is the duty of the atomic bomb survivors. Taking this duty seriously, one drawing in the exhibition explicitly captured the hell mentioned in the message above:20

Figure 2: Drawing of the Chaos after Atomic Bombing by a Survivor

The drawing describes the chaos after the atomic bombing in detail: dead bodies on streets, children crying for their mothers, injured women with their clothes burned by the extreme heat, and people longing for water. The drawing also captures the city still burning, while black rain, the rain highly contaminated with radioactive substances, was still devastating the city.

The memory of the atomic bombing is also conveyed through a wide variety of writings. To offer but one example, Toge Sankichi, a Japanese poet who experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, published a poem, Ningen o Kaese “Give Back the Human,” in 1951.21 Toge wrote this poem when he learned that the United States was considering using an atomic bomb again in the Korean War: 22

chichi o kaese haha o kaese

toshiyori o kaese

kodomo o kaese

watashi o kaese watashini tsunagaru

ningen o kaese

ningen no ningen no yo no aru kagiri

kuzurenu heiwa o

heiwa o kaese

Give Back the Human

Give back my father, give back my mother;

Give grandpa back, grandma back;

Give my sons and daughters back.

Give me back myself;

Give back the human race.

As long as this life lasts, this life,

Give back peace

That will never end.

This poem, as well as the drawing and the storyteller accounts, give a tiny sample of the variety of survivors’ expressions of their memory of the atomic bombing and its effects. Collectively, they have come to form Hiroshima’s and Japan’s communal memory of those events. Individually, they have allowed particular persons to express their own perspective on what happened to those who experienced the bombing. So in the simple examples provided above, the poem is thoroughly about emotional suffering over the loss of loved ones and peace. Meanwhile, the drawing draws our attention to the survivors’ graphic memory about the bombing itself. Survival narratives told by Hiroshima survivors at the museum convey not only what physically happened to the storytellers and those around them but also what they said and heard when the bomb was dropped. Additionally, what makes the oral narratives by the survivors especially powerful is that their stories include what they said and heard before, during, and after the bombing, and the description of their experiences typically goes beyond what they personally experienced. They naturally feel the need to provide some political and historical context, and often some commentary, and then feel compelled to explain what they have learned and what they want people to learn from the bombing. Through all of this and much more, hibakusha have been at the center of constructing a memory for their community and the world of events they hope and pray will never be repeated. So they say together, “No more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki.”

How do we Christians Incorporate the Memory of Hiroshima into our Faith?

As mentioned in the introduction, the year 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. Survivors of the bombing who are mostly in their eighties are concerned about this one question: who will tell our story once we are gone? Let us courageously say, “Christians!” In this final section, I suggest four ways we could incorporate the memory of Hiroshima into our faith in Christ:

- Learn about Hiroshima

- Acknowledge what happened as sin

- Pray for Hiroshima, its survivors, and its future

- Tell others about Hiroshima

1. Learn about Hiroshima

Knowing more about the history of the bombing is important. Understanding the factors that shaped the United States’ policy decision, making sense of Japan’s strategy and circumstances in 1945, assessing the state of scientific knowledge about the bomb’s likely effects, and taking stock of the bomb’s impact on the war in Asia and the postwar world are all worthy pursuits. But our learning should not stop there. As Christians, we are called to share in the sufferings of others and to mourn with those who mourn. Therefore, we need also to learn much more about Japanese survivors’ pain, suffering, and courageous transformation to become ambassadors of peace through encountering the materials by and about the survivors, and better yet, going and listening to those survivors in person, when possible.

Visiting the site where the catastrophe happened and allowing the people who have actually experienced it personally to share their stories typically enables us to relate more empathetically to what happened, and deepens our sense of the reality of those events. For instance, in a recent article in which CNN reported about the record number of foreign visitors to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2013, one interviewee said that visiting the museum made the incident “more of a reality” and less something that was “abstract and remote” for him.23 Additionally, recall the example (8), where the emotional interaction between one American man and a female survivor took place. The conversation clearly indicates that listening to the survivor’s experience moved him to offer an apology; Hiroshima surely became a part of that young man’s reality in a new way. At the same time, it was through this same interaction that the survivor could finally let go of her past and release her hatred toward America. The incident implies that our physical presence with survivors may be meaningful for both those who want to tell the stories and those who want to learn about them. Could there even be hibakusha within our own American communities with whom we and our students could have similar meaningful exchanges?

2. Acknowledge What Happened as Sin

Children of God are also called to be peacemakers. While the most accepted view in the U.S. about the atomic bombing in Japan has been that it was a means to end the war and to save American lives, we need to choose to set aside this historical/political interpretation about the bombing long enough to consider its full range of consequences. To incorporate Hiroshima into our faith means that we prayerfully consider the implications of the quote from Figure 1 above: “[W]e absolutely must never allow it to happen again.” Those words force us at least to identify the suffering imposed by the bombs as tragic and horrifying. Might they even push us further to label the use of such weapons as sin? That troubling question leads me to consider the “Appeal for Peace,” the message Pope John Paul II sent to the world when he visited Hiroshima in February 1981. In the appeal he stated, “War is the work of man. War is destruction of human life. War is death.”24 Furthermore, three years after making this statement, John Paul wrote in his 1984 Apostolic Letter, “Salvifici Doloris,” that a major legacy of World War II was the “horrible threat of nuclear war” and “the possible self-destruction of humanity.”25 Such an unthinkable evil cannot be discounted in a world that has already witnessed the use of two atomic bombs that brought countless numbers of people death and suffering. In the same letter, the Pope also asserted that we suffer whenever we experience evil, which he defined as “a certain lack, limitation or distortion of good.”26 Surely all sides in the war distorted the good; I believe Hiroshima and Nagasaki were moments when whatever ends were achieved, the means employed were morally wrong and catastrophic distortions of the good.

3. Pray for Hiroshima, its Survivors, and its Future Generations

As indicated earlier, each time any country in the world tests its nuclear weapons, the mayor of Hiroshima city protests their testing. The first protest was made in 1968, when France tested its hydrogen bomb.27 Pray that Hiroshima will continue to be persistent with its protests and that each protest will refresh its desire for peace.

Without remembering Hiroshima survivors, one cannot pray for the city. Even today, the survivors in Hiroshima suffer from the health issues caused by their exposure to radioactive materials from the bombing. Yet as the examples in this paper show, their suffering has been not only physical but also emotional, psychological, and spiritual. Pray that even in their old age the atomic bomb survivors will find courage to talk about their experience to the younger generations so that they might find themselves reconciled with what happened in the past through sharing their stories.

While it is important to remember what happened in the past, clearly some pasts are so painful and burdensome that avoidance or ignorance seems not only the easier but the saner route to go. The memory about the catastrophes of the atomic bombings is just such a case. Naturally humans want to forget about pain and suffering, so we tend to let time take our memory of the painful event to the remote past or the far corners of our hearts and minds. Additionally, unless it is one’s own experience, remembering what happened to the previous generation is not easy. It takes time and effort. It takes a willingness to bear the psychological and moral weight of that knowledge. Pray that the future generations of Hiroshima will have the courage to embrace that knowledge and will pass down the survivors’ memory so the catastrophe that once happened in the city will not be forgotten.

4. Tell Others about Hiroshima

We Christian scholars are privileged to serve younger generations through our teaching and scholarship. What we learn about Hiroshima, even in this brief article on survivors’ memory, should not remain just a piece of our private knowledge. Its historical, moral, and perhaps even theological significance is simply too great. So we should bring Hiroshima into our teaching in many disciplines. That may require courage. It might bring some turmoil in our classrooms, for we need to bring something more than what has typically been taught about those events in American schools. It needs to include the memory of Hiroshima from the survivors’ perspectives. It should confront the pain and agony that the survivors went through, witnessed, and remember to this day as well as the loss of what we take for granted today: peace. It should also cause us to pause and reflect upon our shared humanity and the ways in which we all bear the image of God. We might consider as well survivor efforts to think Christianly about their suffering. For example, a Nagasaki survivor, Dr. Takashi Nagai, developed in the first years after the war a theology of the event that asserted that the 8,000 Christians who were killed by the bombing in Nagasaki sacrificed their lives to save the lives of those who would have been victimized if the bomb had not been dropped and the war had continued.28 Their deaths reflected humanity’s sinfulness; their sufferings shared in the sufferings of Christ. His views have had a profound influence on how many Japanese Christians have interpreted the meaning of the atomic bombings. Let us follow their lead in thinking that if what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a part of what Jesus took on the cross with his own blood, we should at least attempt to know and share it with the younger generations, so that they can know the depth of God’s love and sacrifice for them.

In this sense, remembering Hiroshima from its survivors’ perspectives is remembering Jesus’ cross. If we can incorporate the memory of Hiroshima into our faith in Christ through our service for him, perhaps we could positively respond to the survivors’ concern: Who will tell our story once we are gone?29

Cite this article

Footnotes

- Akiyo Cantrell, “Hiroshima Stories: The Construction of Collective Memorialization in Survivors’ Narratives” (PhD diss.: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2006), 1.

- Representative works include Marion Yass, Hiroshima (New York: G. P. Putmam’s Sons, 1971); Robert Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991); Robert Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima in Amarica: Fifty Years of Denial (New York: G. P. Putmam’s Sons, 1995); Yuki Miyamoto, Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012).

- John Hersey, Hiroshima (New York: Random House, 1985). Hersey’s work was originally published in the August 31, 1946 issue of the New Yorker and appeared in book form later that year.

- Robert Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 6.

- United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed February 7, 2015. http://www.un.org/disarmament/content/slideshow/hibakusha/.

- Cantrell, Hiroshima Stories.

- The names used in the excerpts are pseudonyms.

- Cantrell, Hiroshima Stories, 66. Bold faced emphasis is from the original. The symbol “=” indicates length of a vowel preceding it, and each symbol represents a syllable. The symbol “X” indicates an unaudible part, where each “X” represents a syllable.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 53-54.

- Ibid., 136-138.

- Ibid., 54.

- In fact, it was highly discouraged to use English in Japan during the war. Words which were loaned from English, such as terms used in sports or even proper nouns used in names of companies, were replaced with Japanese as Japan’s relationship with the U.S. deteriorated.

- Cantrell, Hiroshima Stories, 56-58.

- Ibid., 154.

- Ibid., 155-157.

- For instance, since 1968, whenever foreign governments experiment their nuclear weapons, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been publicly protesting against these experiments. Both cities also commerorate the day of their catastrophic experience annually with memorial events that include prayer for the victims and public pronouncements that they are strongly against nuclear weapons.

- Cantrell, Hiroshima Stories, 159-161.

- Ibid., 106.

- Ibid., 105.

- Hiroshima Genbakushiryoo Hozonkai [Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Material Preservation Society], Hiroshima: City Dedicated to the Cause of World Peace (Hiroshima: Hamada Shashinkoogeisha, 1969).

- Ibid., 5.

- Richard S. Ehrlich, “Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Attraction More Popular than Ever,” CNN US Edition, June 1, 2014. Accessed February 5, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2014/06/01/travel/hiroshima-peace-museum/.

- Atomic Bomb Museum.org. “Appeal for Peace. Pope John Paul II. Peace Memorial Hall, 25 February 1981.” Last modified December 1, 2005. http://atomicbombmuseum.org/pdf/testimonies/Pope%20John%20Paul%20II.pdf.

- The Holy See. “Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, 11 February 1984.” Accessed February 6, 2014. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father//john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_11021984_salvifici-doloris_en.html/.

- Ibid.

- Hiroshima City. Kakujikken ni taisuru Koogi [Protest Letters Against Nuclear Tests]. Accessed February 3, 2015. http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/0000000000000/1110600391733/index.html.

- Takashi Nagai wrote extensively in the years between 1945 and his death in 1951. His best known work is The Bells of Nagasaki, available in many editions. For a helpful analysis of his work and other religious reflections on the collective memory of the bombing, see Yuki Miyamoto, Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012).

- I would like to thank the editors of this volume for their valuable comments and suggestions. I am especially thankful to Richard Pointer for his generous help and encouragement.