American civil discourse is in decay. It is commonplace that many citizens not only disagree but do so disagreeably. However, disagreeableness need not be a feature of our discourse. After diagnosing several instances of decayed discourse as failures of intellectual virtue, the article offers suggestions for fostering virtues—such as humility, open-mindedness, and fair-mindedness—that can help us disagree without being disagreeable. The pursuit of intellectual virtues, the author argues, can help us build better discourse. Nathan L. King is Professor of Philosophy at Whitworth University and author of The Excellent Mind: Intellectual Virtues for Everyday Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

A recent headline in The Onion reads, “Online Activists Unsure about Offensiveness of Article, Figure They’ll Destroy Author’s Life Just In Case.”1 The headline is funny only because it studiously mimics real life. Our discourse has decayed so much that it is difficult to tell the difference between sober and satirical coverage of it.

Anyone connected to the internet knows about the spectacle of trolling: the practice of posting offensive, demeaning, or threatening remarks online. It has become nearly impossible to peruse a readers’ comment section without finding someone dismissed as a “fascist,” “snowflake,” “bigot,” “SJW,” “loon,” “nut job,” “hippie,” “shill,” “deplorable,” or worse.

Please take a moment to ask yourself: Do I feel reluctant to discuss controversial topics online or in public? Am I uneasy when I discuss Christianity, atheism, abortion, gender issues, Trumpism, vaccine hesitancy, racial injustice, or other such topics?

If you are like me, you answered yes. Maybe our reluctance stems from a fear of being punished for stating our views. Maybe we are afraid that others will criticize us before even understanding what we have said. Maybe we fear that they will brand us with a label we would rather avoid. Or maybe we fear that if we state our opinion, we’ll be lumped together with ideas and people we disavow.

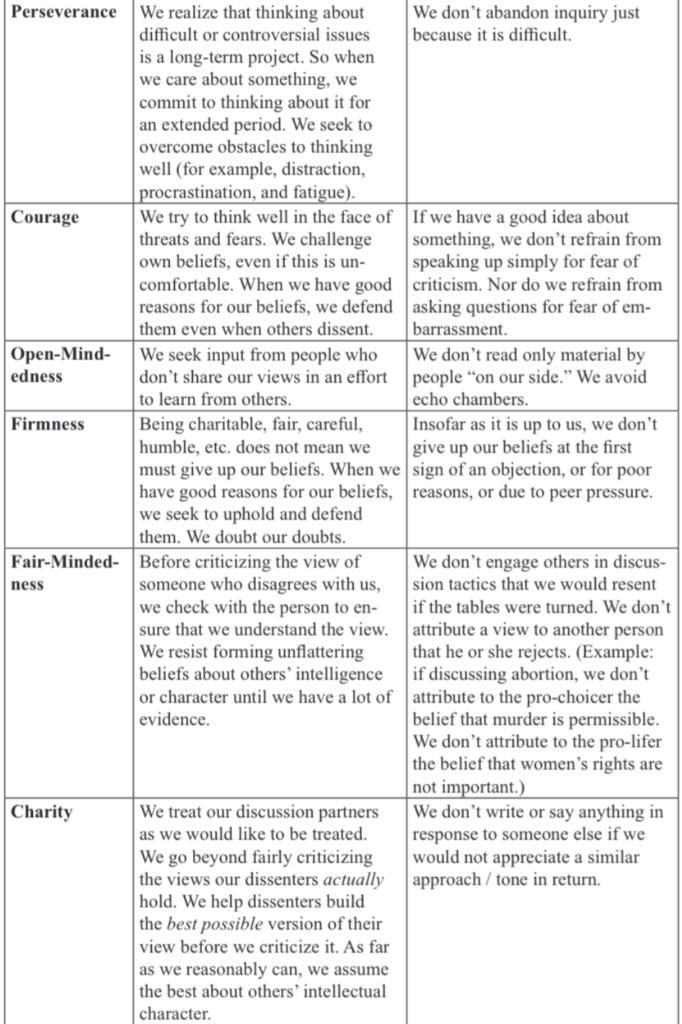

If so, it is worth trying to figure out how we can make our disagreements less disagreeable. It is worth sketching a blueprint for how to build better discourse. In this paper, I attempt such a sketch. My central claim is that the pursuit of intellectual virtues—including carefulness, humility, open-mindedness, firmness, fair-mindedness, charity, and perseverance—is essential to any successful effort to build better discourse.

Foundations

I’m a philosopher by trade. So, my union card requires that I start by defining my terms, providing at least two caveats, and making explicit my underlying assumptions.

Let’s start with the terms. To disagree with someone is to take an attitude toward a claim that is incompatible with the attitude the other person takes. For example, if I think that capital punishment deters crime and you think it does not, then we disagree. A milder kind of disagreement: one of us believes a claim and the other suspends judgment about it. If I believe in God and you are agnostic (you neither believe nor disbelieve in God, but suspend judgment), we count as disagreeing.

Next, to be disagreeable toward someone is to express disagreement in a way that goes beyond merely stating our views. It is to express our disagreement in a way we reasonably think will upset another person. Disagreeableness is less about what we say than about how we say it. To avoid being disagreeable, we need not refrain from expressing our controversial views. Rather, we must seek to ensure that whatever offense our expression causes is due to our message itself—not the way we deliver it.

Now, the caveats. First, expressing disagreement is not always disagreeable.Suppose you and I are talking about tomorrow’s weather forecast. I say it will snow, and you say it will not. You disagree with me. Are you therefore acting disagreeably? Perhaps not. You might express your disagreement while remaining perfectly pleasant. So, just expressing disagreement need not involve being disagreeable.

Nor must disagreement bespeak disagreeableness when we move into more controversial territory. Here is a thought experiment from philosopher Alvin Plantinga. Suppose you are a Christian. You believe that God exists, that God became incarnate in Christ, and that he died for our sins and rose again. You believe the doctrines stated in the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed. You therefore believe that those who deny these claims believe something false. Are you thereby being disagreeable toward these people? Suppose you are aware that many intelligent people reject your Christian beliefs. You realize that you’re finite and fallible, and that you’re a sinner. You have studied objections to Christianity and have learned much from them. You are not certain that you’re right. But for all this, in your judgment, Christianity is true. When you report this to your dissenting friends—humbly but directly—are you thereby being disagreeable? It’s hard to see why. And if you are not, then even when it comes to topics as controversial as whether only one religion can be true, disagreement need not involve disagreeableness.2

Second caveat: sometimes, it is appropriate to be disagreeable. Jesus did it, after all. Recall the passage from the Gospel of John, chapter 2. When he cleansed the Temple, Jesus made a scene. He drove the money-changers out with a whip. He accused them of corruption. When they asked him what right he had to do these things, he chided them: “Destroy this Temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” Jesus surely knew that his words and actions would make Temple authorities uncomfortable. By any reasonable account, he acted disagreeably. But no Christian can think he did something inappropriate. As Jesus shows us, disagreeableness can stem from love instead of hatred, rare though such cases may be.

Other moral reformers’ lives illustrate the same point. Think of Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., William Wilberforce, and others. In their battles against oppression, these people were right to express their disagreement in disagreeable ways.

In sum, we should reject the idea that merely expressing disagreement is always disagreeable. And we should reject the idea that we should never be disagreeable. The remainder of our discussion requires milder assumptions, namely these: Given the state of public discourse today, it would be good if we could cut down on disagreeableness that doesn’t serve some good end. And it would be good if we didn’t automatically assume that our own favored ends are so important that they automatically justify our being disagreeable, or that they make disagreeable speech wise.

Here is one further working assumption: in intellectual matters, no less than in other matters, the Silver and Golden Rules apply. We have a duty not to do to others what we would not want done to ourselves (the Silver Rule). And we have a duty to do to others what we would want done to us (the Golden Rule). When asked to identify the greatest commandments in the Jewish Law, Jesus said, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’This is the first and greatest commandment.And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments” (Matt. 22:37-40). Our duty to love others is not rendered void when we engage in intellectual conversations, even conversations about disputed topics. There are intellectual Silver and Golden Rules. If we think we can divorce our habits of discourse from our efforts to love others, we have notfully grasped the implications of Jesus’ words. We will not fulfill the command to love others if we serve in soup kitchens and help little old ladies across the street, and then go home, crack open our laptops, and treat our online dissenters carelessly, closed-mindedly, and uncharitably. On the contrary, treating others well in intellectual endeavors is part of what it is to follow Jesus’ love commandment in real life. Inconveniently, though gloriously, that command extends to the way we treat our enemies.3

Support Beams

If public discourse were a building, our habits of thought would be the support beams. Applying the metaphor, many of the thinking habits that appear on today’s blogs, news feeds, and social media sites are the equivalent of rotted timbers. If we want to rebuild our dilapidated discourse, we will need to clear them away and replace them with something sturdier—namely, intellectual virtues.

Intellectual virtues are the cognitive character traits of excellent thinkers—cu-iosity, intellectual carefulness, intellectual autonomy, intellectual humility, intellectual honesty, intellectual perseverance, intellectual courage, open-mindedness, intellectual firmness, fair-mindedness, intellectual charity, and so on.4 These virtues differ from each other in that they concern different areas of activity or challenge. For example, intellectual autonomy is the virtue we need to take responsibility for our own minds—to think for ourselves, even if not by ourselves. Intellectual courage is the virtue we need to keep seeking, maintaining, or sharing knowledge in the face of threats(such as ridicule, painful self-realization, and even physical harm).

Here is what intellectual virtues have in common. They all involve excellence in our thoughts, motivations, and actions in relation to truth, knowledge, and understanding. Virtuous thinkers believe knowledge is valuable in its own right, and not just for the earthly goods it delivers. They desire understanding. They feel pleased when they discover the truth, and feel uneasy at the thought of believing falsehoods. And they act—habitually—in order to get knowledge, to keep it, and to share it with others. (A salient reminder: civil discourse is standardly defined as discussion undertaken for the sake of knowledge and understanding. If this is right, then the goal of civil discourse is to achieve the very goods—knowledge and understanding—that virtuous thinkers want. Good civil discourse and intellectual virtue are tightly linked.)

Failures of Intellectual Virtue in Civil Discourse

It is both plausible and helpful to diagnose many failures of civil discourse as failures of intellectual virtue. Though the discussion below is nowhere near exhaustive, it does represent several ways in which such failures are harming our conversations.

Carefulness

We will begin with intellectual carefulness, the virtue that helps us avoid falsehood and irrational belief in cases where such ills are particularly salient (that is, when we are particularly prone to mistakes). The careful thinker is motivated to avoid such mistakes and is competent at doing so. By contrast, careless thinkers are insufficiently motivated to avoid falsehood and irrationality and are bad at doing so. This deficiency often rears its head in civil discourse. Consider this example:

The Ad Hominem Fallacy (argument against the person): This fallacy attacks the individual who has stated a view or argument instead of providing a rational critique of that view or argument. For example: “Smith defends the importance of health care for the poor. But Smith is just a soft-headed red communist. So, you shouldn’t believe a word she says about health care.” This way of thinking simply attacks the person giving an argument or expressing a view. It does not provide any reason to think Smith’s argument itself is unsound, or that her view is false. It is an intellectual shortcut around Smith’s evidence, and a hasty judgment.

The ad hominem fallacy is already familiar to most readers, so we won’t spend more time on it. Instead, let us consider a second fallacy:

The Attitude-to-Agent Fallacy (proposition-to-person):This fallacy occurs when our thinking moves straight from the attitude a person takes toward a proposition to a negative assessment of the agent (person) herself. For example, in a recent interview, comedian Steve Harvey was alerted to the fact that some people do not share his belief in God. Upon hearing about others’ non-belief, Harvey remarked, “Well then, to me, you’re an idiot.”5

To see why such thinking is bad, consider some analogies. If you see a basketball player miss a free throw, you shouldn’t think she is a lousy shooter. If you watch a baseball player strike out, you shouldn’t immediately think he is a bad hitter. The fallacy is to move from a judgment about a single performanceto a judgment about a person’s general tendencies or character. Seeing a single bad performance usually only gives us reason to think that someone has made a mistake on the given occasion. Now, our beliefsare like cognitive performances. Taken one at a time, they are isolated events. Just as we shouldn’t think that someone who trips once is a clumsy person, we shouldn’t think that someone who believes something false is stupid. Nor should we think that he has bad moral or intellectual character. What might we think instead? Perhaps we should think the person just does not have the same evidence we have. Or maybe we should think he has the same evidence we have but has made a mistake in assessing it. Either explanation is more reasonable, and more careful, than the idea that he is stupid or corrupt. And, come to think of it, don’t we provide such charitable explanations of our own mistakes?

Our next fallacy is growing in popularity, at least if my Facebook feed is any indication. Here’s an example:

The Argument / Claim Conflation:This fallacy confuses the reasons given for a claim with the claim itself, so that if one rejects an argument for a claim, they are accused of rejecting the conclusion of that argument. Here’s an example: Suppose I give a Marxist, critical-theory-based argument for social justice. You find my argument unsound. I infer that you are against social justice itself. In this case, I conflate your assessment of my argument with your assessment of my conclusion. I think you are rejecting my main point, but you’re only rejecting how I got there. For me to make this move is to confuse the reasons I have given for a claim, with the claim itself. Such thinking ignores an important fact: There can be more than one reason for endorsing a claim. You can reject innumerable arguments for a claim without rejecting the view itself. To sensibly endorse a claim, you need only think that there’s one argument or other good reason for it.

One pernicious feature of the Argument / Claim Conflation is that it leads to a lot of friendly fire. It leads members of a given group to eat their own. Do you reject any of the reasons people in your group offer for their views? If so, then watch out—you might find yourself labeled a heretic or a deserter.

This is, in part, an artifact of our culture’s move toward tribalism, a set of thought and speech codes that demands absolute deference to the beliefs and reasons of the group.6 Anyone—even a devoted group member—can be “voted off the island” for failing to comply. Are you a political liberal who harbors a few doubts about your tribe’s arguments for abortion-on-demand? Be advised, your friends may question your commitment to the pro-choice cause. Are you a theological conservative who rejects the arguments for a literal reading of Genesis? Take heed. You may find yourself booted from church for denying that God created the world. Pretty clearly, such thinking is bad for our discourse.

Our final fallacy is well known to most logic students:

The Straw Man Fallacy:This fallacy involves weakening another person’s view or argument in a way that makes it easier to attack. Example: Two students are talking in the dormitory lounge. One of them, a staunch Calvinist, is eager to defend God’s providence. He says to his Arminian friend (who takes a strong view of free will), “You believe in robust human freedom, so you deny God’s providence.” The other student retorts, “You believe that God’s providence constrains human freedom, so you must think that God’s actions are the cause of evil the world. You therefore think that God is evil.” 7

It’s safe to say that neither student recognizes his views as they are described by his opponent. Each has weakened the other’s view in order to make it easier to defeat.

Such thinking is the intellectual equivalent of refusing to box a real opponent and setting up a punching bag instead. Of course, anyone can beat up a straw man; a one-punch knockout is not a medal-worthy performance. Likewise, it’s no intellectual accomplishment to defeat a weakened version of someone’s position.

Here’s something puzzling. All of the fallacies just discussed are easy to understand. They are simple enough to be grasped by freshman, children, and even philosophy professors. Despite this, they make up a sizeable percentage of our discourse about controversial topics. How could these fallacies be so easy to see, but so hard to avoid? My own sad suspicion is that we lack sufficient motivation to resist them—perhaps because such resistance is uncomfortable. Embracing these fallacies provides fast relief from the cognitive dissonance that arises when we realize that our dissenters just might have a point. If we want to build better discourse in our community, we must resist seeking such relief. To help with such resistance, we should consider refreshing our skills in logical reasoning and critical thinking. Short of this, we can at least stop and ask ourselves questions like these: Do I really have good reason to think I’m right here? Am I jumping to conclusions? Are there alternative conclusions someone might draw, given my evidence? To ask these questions is to take a step in the direction of intellectual carefulness.

Humility

Intellectual humility is the virtue that enables us to assess our intellectual limitations or weaknesses reasonably, and to own these shortcomings by doing something about them.8In the context of public discourse, I suggest that humility has at least two clear applications.

First, when we discuss controversial topics, we must bear in mind that these topics areusually controversial because they are deep and multi-faceted. We are rarely aware of all the evidence that is relevant to our controversial beliefs about ethics, politics, law, science, or religion. But if this is right, then we must admit that there is evidence “out there” that we don’t have. Some of it probably counts against our views. This need not force us to abandon our cherished beliefs. But surely it should make us more cautious and self-reflective.

Here is a test, adapted from the work of Fordham University philosopher Nathan Ballantyne.9 Identify a controversial belief of yours. Now, mentally transport yourself to a library. On the shelf before you are dozens of books whose titles suggest that they attack your controversial belief. Are you nervous? If so, then you acknowledge that those books may contain evidence against your beliefs—evidence that you don’t have. And you are acknowledging that this evidence is relevant to what you should believe. Now suppose you open all those books and find that they are filled with blank pages, or Garfield comics. Do you feel relieved? If so, again, you’re admitting that the arguments you thought were in those books might have reduced your confidence in the disputed belief.

When it comes to our beliefs about controversial topics, there is often a lot of available evidence that we don’t have. This is one of our cognitive limitations. Part of what it means to own this limitation—part of what it means to be humble—is to give this evidence some weight.

Here’s a second way that owning our limits is important for public discourse. Whatever we say about our grasp of the evidence surrounding our controversial beliefs, we are surely limited when it comes to our knowledge about what’s on others’ minds. Suppose our dissenter supports Planned Parenthood, or that he voted for Donald Trump. We cannot justifiably infer from these facts that she supports Planned Parenthood because she doesn’t care about the unborn, or that he voted for Trump out of disdain for immigrants. People have all kinds of reasons for their beliefs and actions. We cannot normally know what these are without asking. We’re not clairvoyant. To be humble in the midst of civil discourse, we must slow down, admit that we have limited access to others’ minds, and begin to listen.

Open-Mindedness

Open-mindedness is the intellectual virtue that enables us to transcend our current perspective for the sake of learning—to take seriously the merits of new or challenging views.10This trait obviously rules out dogmatism and intellectual inflexibility. If we are open-minded, we will not dismiss new or alternative views without good reason. Rather, we will be willing and able to learn from people whose views oppose our own, or are simply different.

Now, some people get nervous about open-mindedness. They worry that it will lead to a lack of conviction. Thus, the oft-repeated line, “Don’t be so open-minded your brains fall out.” However, open-mindedness is fully compatible with confident conviction. This, too, is reflected in our language. We sometimes say things like, “I’m really confident in my views about marriage, but I’m open to counterevidence”; or “I’m quite sure that the Gospels are historically reliable, but I’m willing to hear the arguments on the other side.” This shows that open-mindedness is not the same as spinelessness. We can be very confident in our beliefs, yet remain open-minded about them. Further, open-mindedness requires us to consider the merits of other views. In the rare cases where a view has no merits, open-mindedness does not require that we consider it.

Here’s something that’s easy to miss. Open-mindedness can apply not just to our beliefs about controversial topics, but also to our beliefs about the people with whom we disagree. We shouldn’t just be open-minded to evidence against our beliefs about, say, God or morality. We should be open to changing our views about theists, atheists, pro-choicers, and pro-lifers.11 We must acquire the first instinct of Abraham Lincoln. As legend has it, one of Lincoln’s aides was talking about a man of whom Lincoln had a bad first impression. After a moment’s thought, Lincoln remarked, “I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.”12

Firmness

Earlier, I argued that open-mindedness needn’t lead to our becoming wishy-washy. Another reason to think this is that in a fully virtuous mind, open-mindedness will be complemented by the virtue of firmness. Whereas open-mindedness leads us to transcend our own perspective, firmness enables us to maintain that perspective. If we are intellectually firm, we won’t tend to give up our convictions without good reasons to do so. We won’t change our views to fit the current intellectual fashion. When we encounter objections to our well-considered views, we will doubt our doubts even as we consider new evidence.13 Thus, if we are open-minded and firm in our thinking, we’ll avoid both dogmatism and spinelessness.

Perseverance

Finally, a word about intellectual perseverance.14This is the virtue that enables us to overcome obstacles to our gaining, keeping, and sharing knowledge. Among such obstacles are distractions, our own limits, our blind spots, the sheer difficulty of our tasks, discouragement from others, oppression, depression, and our own laziness.

When it comes to rebuilding our discourse, the task ahead is difficult. To “do” public discourse well, we must:

• Avoid treating others as we would not want to be treated (fair-mindedness)

• Treat others as we ourselves want to be treated (charity)

• Acknowledge and own our intellectual limitations (humility)

• Transcend our own perspective by considering new or contrary views (open-mindedness)

• Maintain our own perspective unless given good reason to abandon it (firmness)

Further, we must do all of these things and more while our cherished beliefs are on the line, and thus while we’re emotionally distraught, or at best uneasy. Good public discourse requires so many virtues because it requires us to operate well in several different spheres of activity, each of which corresponds to its own virtue, all at once. We can envision the situation like this:

The way these spheres overlap in public discourse explains why the activity is so challenging: it requires us to do several difficult tasks at once. It thereby shows that to achieve our goals in this area, we’ll require a great deal of perseverance—for perseverance is the virtue needed to persist in difficult tasks. If we want to build better discourse, we should prepare for long and heavy labor.

In the Christian context, the difficulty of civil discourse also underscores the importance of grace. Because it is so hard to build and maintain intellectually virtuous discourse, we should not be surprised to find others making mistakes, running afoul of virtue, and running headlong into intellectual vice. This will be disappointing. But unless we have reason to think we are somehow special, we, too, should expect to make mistakes. How, I wonder, will we want others to respond when we do? And what does that say about how we should respond to their failures of virtue?

There is a genuine opportunity here. American public discourse is utterly graceless. If Christian communities can demonstrate grace in the midst of honest, earnest, controversial discussions, the secular world is sure to notice. With so many voices yelling, insulting others, casting others as the enemy, and so on, Christians can decide to do something different. Gentleness, in the present context, is bound to stand out.15

Steps Toward Intellectual Virtue

Here is a serious problem: if the state of our discourse is any indication, most of us—including most Christians—do nothave the virtues needed to express grace in the midst of controversy. For plausibly, if we did, our speech would be in much better shape than it is. If we want to build better discourse, we will need better carpenters. If we want to improve our conversations, we will need to improve the intellectual characters of the people doing the talking.

May I suggest that we start with ourselves? True—it would be more com-fortable to begin by pointing out others’ flaws. But if we do this, we’ll find the proverbial three fingers pointing back at us. Some time ago, my daughter, Lily (then nine years old) pointed out a mistake her six-year-old sister Adele had made. Because Lily often struggled with the same mistake, I apprised her of the one finger / three fingers dilemma. Ever the confident father, I was sure that this lesson would be life-changing for Lily. But she simply furrowed her brow and pointed back at her sister—with all fingers extended in the same direction! Lily’s cleverness aside, I suggest that in seeking to reform intellectual character, we start with our own minds.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn considers our temptation to place all the good people on our side and all the bad ones on the other. Here are his famous words:

If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.16

The same is true when it comes to intellectual character. It is not as though all the smart, honest, humble, open-minded folks are on our side of a given issue, and all the stupid, lying, arrogant dogmatists are on the other. Rather, we probably all have elements of all these traits within us. In sum, we find ourselves somewhere between intellectual virtue and vice.

So, suppose we want to reform our own intellectual character. What should we do? It would be best to draw from a catalog of interventions, all rigorously tested by cognitive and social psychologists and shown to guarantee progress in intellectual virtue. Alas, no such catalog yet exists. There is reason to hope for progress on this front in the coming years. In the meantime, the following suggestions can get us started.

First, we can regularly remind ourselves of the kind of intellectual character we want to have. There are some reminders, geared toward classroom and online behaviors, in the appendix to this essay. These are just examples. Readers are invited to construct their own, suited to their particular activities and tendencies. (There is empirical evidence that such reminders really work. In one study, when participants regularly read the Ten Commandments, this drastically reduced their tendencies toward academic cheating.17)

Second, we can find role models—people whose stories display, in vivid detail, what it looks like to be intellectually courageous, humble, open-minded, persevering, and so on. Like nothing else could, these stories enlarge our vision of an excellent mind. There’s a palpable difference between just telling yourself to be more intellectually courageous (on the one hand) and imagining Martin Luther King, Jr. crossing the Edmund Pettis Bridge (on the other). Narratives teach us what the intellectual virtues look like “in action.” And they provide inspiration as we seek to improve our own intellectual character.18

Third, we can choose our situations wisely.20 Imagine you find yourself stepping up to the plate in a major league baseball game. Your job is to get a hit and help your team win. The trouble is, you have only your current “baseball character”—your current abilities, tendencies, and habits—to rely on. You might try very hard to get a hit. But you’re not trained to do it. You haven’t taken the batting practice, instruction, and physical training needed to get a hit. You’ll probably strike out. And so will I.

We may be in a similar situation when it comes to civil discourse: we find ourselves facing a difficult task, but our intellectual character is not yet suited for it. If so, then we’ll need to practice. We must identify the kinds of things that virtuous thinkers do, and begin to do those things. We must engage in practices that challenge us to grow toward intellectual virtue by performing intellectually virtuous acts. As Aristotle says, “the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them.”21 To this end, below are two exercises intended as opportunities for growth in such intellectual virtues as humility, courage, open-mindedness, fair-mindedness, firmness, and perseverance. (To make things fair, I promise to do them, too. I need them as much as anyone does.)

Visit the Coffee Shop: find someone with whom you disagree about a topic that is important to both of you. Take this person to coffee and discuss your disagreements. Don’t try to “convert” the other person to your side. Instead, see what you can learn about the other person’s reasons for holding their view. Listen intently. Ask questions. Check your defensiveness. Do not criticize the other person’s view until you can characterize that view to the other person’s satisfaction. As much as you can, resist the temptation to focus on what is wrong with the other person’s view. Instead ask, “What can I learn from this person?” (Notice: asking this does not require you to abandon your own views!) When the appointment is over, jot down a few notes about what you have learned. Focus on good, strong, or true points about the other person’s view. Identify strengths in the other person’s in-telligence and intellectual character. If it is too much to focus on such strengths, at least identify ways in which the other person is not, intellectually speaking, as bad as you had previously thought. Extra credit: make a habit of this exercise.

Read the Opposition: select a controversial topic about which you have a firm view. Then seek and read the work of someone on the opposite side. Try to find the most reputable source you can. Read this person’s work carefully, with the intention of learning. Work to interpret the opposing view as you would want your own view to be interpreted. Before you criticize the opposing view, ensure that you have understood the best possible version of it. Extra-credit: repeat this exercise several times.

These are just sample exercises. It is easy to think of others, and readers are encouraged to do so. See Appendix A for a few more ideas. This is an area in which we need all the creativity we can muster.

Conclusion

Of course, we should not think we can shore up our crumbling discourse just by implementing the plan suggested above—or any other. I claim only that these practices can help us to make progress in our remodeling project. Given the current state of our discourse, even mild progress would be something for which to be grateful. To fully rebuild our discourse, I suspect we will require divine assistance. We will need a contractor whose wisdom and resources exceed our own. For that, we must look to the Carpenter who raised His own temple after three days in the grave.22

Appendix: Dos and Don’ts for More Virtuous Conversations

Below are some Dos and Don’ts concerning intellectual virtue and civil discourse. These are aspirational rather than descriptive and are stated colloquially, with a university community in mind.

Cite this article

Footnotes

- The Onion, “Online Activists Unsure about Offensiveness of Article, Figure They’ll Destroy Author’s Life Just in Case,” October 10, 2017, https://www.theonion.com/online-activists-unsure-about-offensiveness-of-article-1819580390.

- This point is inspired by Alvin Plantinga’s response to the charge that believing Christian doctrine in the face of dissent is automatically arrogant. See his Warranted Christian Belief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 447.

- For a helpful discussion of this theme, see Arthur Brooks, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt (New York: Broadside Books, 2019).

- For an introductory treatment of intellectual virtues, see Nathan L. King, The Excellent Mind: Intellectual Virtues for Everyday Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). For an introduction intended for Christian readers, see Philip Dow, Virtuous Minds: Intellectual Character Development (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2013). For wise guidance on educating for intellectual virtues, see Jason Baehr, Deep in Thought: A Practical Guide to Teaching for Intellectual Virtues (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press). For several insightful essays at the intersection of intellectual virtue and civil discourse, see Gregg Ten Elshof and Evan Rosa, eds., Virtue and Voice: Habits of Mind for a Return to Civil Discourse (Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian Press, 2019).

- This example is drawn from Robert K. Garcia and Nathan L. King, “Toward Intellectually Virtuous Discourse: Two Vicious Fallacies and the Virtues that Inhibit Them,” in Intellectual Virtues and Education: Essays in Applied Virtue Epistemology, ed. Jason Baehr(New York: Routledge, 2016), 212-213. As Keith Wyma has pointed out to me, this reasoning goes in the opposite direction of the ad hominem fallacy. Instead of using some feature of a person to discredit a claim, it uses some feature of the claim to discredit the person who holds it. The logical chasm is just as wide in both directions.

- Thanks to Beck Taylor for drawing this connection to my attention.

- For discussion of the specific kind of straw man fallacy that occurs in this example—assailment by entailment—see Robert K. Garcia and Nathan L. King, “Toward Intellectually Virtuous Discourse: Two Vicious Fallacies and the Virtues that Inhibit Them,” in Intellectual Virtues and Education: Essays in Applied Virtue Epistemology, ed. Jason Baehr,(London: Routledge, 2016), 202-220.

- I glean this account of intellectual humility from Dennis Whitcomb, Heather Battaly, Jason Baehr & Daniel Howard-Snyder, “Intellectual Humility: Owning Our Limitations,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 94.3 (2017): 509-539.

- ee Ballantyne, Knowing Our Limits (New York, Oxford University Press, 2019), chapter 7.

- For discussion see Jason Baehr, “The Structure of Open-Mindedness,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy41.2 (2011): 191-213; and Baehr, “Open-Mindedness,” in Being Good: Christian Virtues for Everyday Life, eds. Michael Austin and Doug Geivett, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 30-52. My basic account of open-mindedness, along with the “brains fall out” remark, is gleaned from Baehr’s work.

- For a good contemporary example see Evan Low and Barry Corey, “We First Battled over LGBT and Religious Rights. Here’s How we Became Unlikely Friends,” The Washington Post, March 3, 2017, https://washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2017/03/03/we-first-battled-over-lgbt-and-religious-rights-heres-how-we-became-unlikely-friends.

- This remark is attributed to Lincoln in multiple locations. I have not been able to track down the original source.

- For further discussion of firmness, see Robert Roberts and Jay Wood, Intellectual Virtues (New York: Oxford University Press), chapter 7.

- For further discussion of perseverance see Heather Battaly, “Intellectual Perseverance,” Journal of Moral Philosophy 14.6 (2017): 669-697; Nathan L. King, “Intellectual Perseverance,” in The Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology, ed. Heather Battaly,(New York: Routledge, 2019), 256-69.

- In this connection, every Christian interested in discussing Christianity in the public square should read Dallas Willard, The Allure of Gentleness: Defending the Faith in the Manner of Jesus(New York: HarperOne, 2015).

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956, authorized abridged version (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2007), 75.

- For discussion, see Christian Miller, The Character Gap: How Good Are We? (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), chapter 6.

- For numerous examples, see the following works (listed alphabetically): Jason Baehr, Cultivating Good Minds, available at http://intellectualvirtues.org/; Jason Baehr, Deep in Thought: A Practical Guide to Teaching for Intellectual Virtues (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press); Philip Dow, Virtuous Minds: Intellectual Character Development (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2013); Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (New Haven: Yale, 2001);Nathan L. King, The Excellent Mind: Intellectual Virtues for Everyday Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021); Robert C. Roberts and Jay Wood, Intellectual Virtues: An Essay in Regulative Epistemology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); and Rachel Swaby, Headstrong: Fifty-two Women Who Changed Science and the World (New York: Broadway, 2015).

- The strategy explored in this paragraph is an extension of a strategy for growth in moral character recommended by Christian Miller. See Miller, The Character Gap: How Good Are We? (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), chapter 9.[/efn-note]Do certain situations tend to bring out the worst in my thinking? Does a certain blog regularly lead me to think in unfair, uncharitable ways? Am I simply unable to talk about a given topic—say, race, vaccines, or election conspiracies—without thinking that those who oppose me are fools? Am I unable even to watch the evening news without my passions—my fear, my anger, my need to belong—disrupting my ability to think clearly and carefully? These may be signs that my intellectual character is not mature enough for the situations that are giving me trouble. If such a possibility rings true in your case, consider humbly admitting that you’re not ready for the difficult situation, and simply take a break from it. Perhaps with some additional training, you and I will be better prepared for future challenges. In the meantime, we can develop our intellectual character by training on less difficult tasks.

Training—that’s the key word. Perhaps our failures in intellectual discourse stem not from a lack of trying, but from a lack of training.19I owe this distinction to James Bryan Smith. See Smith, The Good and Beautiful God (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2009).

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, BK 2.1.

- For helpful discussion, the author thanks Kristie King, Will Kynes, Rick Langer, Josh Leim, and Beck Taylor. An earlier version of this essay, titled “Building Better Discourse,” was published in Nathan L. King and Beck A. Taylor, eds., President’s Colloquy on Civil Discourse: Civil Discourse and the Christian University (Spokane WA: Whitworth University, 2018), 29-48. Thanks to Whitworth University for permission to rework the essay for the present issue of Christian Scholar’s Review.