Perry L. Glanzer notes that over the past two decades institutional growth in Christian higher education has slowed to a trickle in the West, but in Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa it has taken off. The remarkable vigor and growth of Christianity in the global South and East is an obvious driver behind the rise of new Christian universities. Drawing upon a recently compiled database of Christian colleges and universities, this article examines the current state of Christian higher education around the world and evaluates how it is faring in the light of larger trends in Christian and global higher education. Mr. Glanzer is Associate Professor of Educational Foundations at Baylor University.

Scholarship about the global nature and growth of the Church outside North America has far outpaced attention to global Christian universities.1 Yet, based on initial findings, it appears that some of the same paradigm-shifting points made about the growth of Christianity in the global South and East appear to apply also to Christian universities as well. Over the past two decades, institutional growth in Christian higher education has slowed to a trickle in the West, but in places such as Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa, it has taken off. In Africa alone, more Christian universities have been organized over the past decade than have commenced in all of the rest of the world. In other cases, the type of growth is changing. Latin America is seeing the growth of more Protestant universities than ever before, as rising Protestant movements there mature and take on more institutional tasks. There are now more Lutheran and Presbyterian universities in Latin America than in Europe.2 And just as the Anglican churches across Africa now vastly outnumber those in the United Kingdom, so too there are now more overtly Anglican universities in Africa than in the U.K. The remarkable vigor and growth of Christianity in the global South and East is an obvious driver behind the rise of new Christian universities. This essay seeks to dig deeper into the recent findings to evaluate the current state of Christian higher education around the world.

The article draws upon a recently compiled database of Christian colleges and universities3 to evaluate how these institutions are faring in the light of larger trends in Christian and global higher education.4 The trends examined include nationalization and secularization, globalization, massification, privatization, and the professionalization (or what some call commodification) of higher education. Based on the findings, it appears that Christian higher education continues to survive the significant challenges posed by nationalization and secularization. Furthermore, it has benefitted significantly from the privatization of higher education and to some degree from the globalization and massification of higher education. While Christian higher education will continue to capture only a small niche market in most countries, the development of Christian colleges and universities that take advantage of professionalization and privatization in ways that serve the Church and the common good poses a hopeful development for Christian higher education. How these developments can be enhanced will be the future concern of Christian higher education leaders that is discussed at the end of this article.

Beyond Bible Schools and Seminaries: Defining Christian Colleges and Universities

The database of Christian colleges and universities used in this article was compiled with the help of two other colleagues.5 We identified and listed all the explicitly Christian colleges and universities found around the world using the following definitions of “Christian” and “college and/or university.”

“Christian”

Traditionally, scholars have approached the topic of religious higher education in North America by focusing upon “church-related” colleges and universities.6 The advantage of this approach is one does not have to determine what is meant by a “Christian” university. The problem, however, is that describing a college or university as “church-related” provides little information about the degree to which a particular church or its theological beliefs and practices actually influence a college or university. Furthermore, in light of the secularization of a vast number of these institutions and the range of church relations they hold, many would question whether some of these institutions would identify themselves as Christian and in what way they might do so (for example, while Duke University may be church-related, no one would define it as a Christian university). Finally, with the decline of the importance of denominational affiliation, using the criteria of “church-related” becomes problematic considering many universities are started by individuals who are perhaps associated with certain particular movements or churches but not a specific denomination (such as Oral Roberts University, Regent University, and others) or are simply nondenominational (such as Wheaton College, Azusa Pacific University, and others).

Consequently, we defined as “Christian” those universities or colleges that currently acknowledge and embrace a Christian or denominational confessional identity in their current mission statements and also alter aspects of their policies, governance, curriculum, and ethos in the light of their Christian identity (for example, required courses in Christian theology or the Bible; the presence of Christian worship at protected times that is supported by the institution; and a college-funded Christian chaplaincy).7 We identified Christian denominations as those that are historically understood as fitting within Protestant, Catholic, or Orthodox confessions of faith.

“College or University”

In a global setting, the terms “college” and “university” also have numerous understandings. Admittedly, our understanding was shaped by our North American sensibilities. We only included institutions that are the equivalent of baccalaureate colleges, master’s colleges and universities, and doctoral-granting universities. We did not include what the Carnegie classification would describe as special focus institutions, such as seminaries, teachers colleges, schools of engineering and technology, or associate’s colleges.8 To make a clear delineation with seminaries, we only listed colleges that offer majors in at least two distinct areas of study beyond those related to church vocations (such as theology, Biblical studies, church music, and Christian/Church education). We also only included universities that have at least one faculty/school beyond theology and/or canon law.

We did not include colleges within universities that only refer to disciplinary units (for example, colleges of arts and sciences) or residential colleges within universities that do not offer courses but largely provide accommodation or cocurricular related activities (for example, some of the colleges listed on denominational lists9). However, we included colleges that exist in affiliation with larger universities and come under that university’s jurisdiction but offer a full degree. Certain colleges or university colleges in systems of education influenced by an English model of organization share this characteristic, especially in India. These colleges offer particular courses of study similar to liberal arts colleges in North America.

Using the definitions described above, we gathered information about Christian colleges and universities around the world.10 Our original search found 579 institutions that fit our categories in those regions outside of Canada and the United States.11 Since the publication of these original findings, the updated cur- rent number of institutions has grown to 595. The International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education (IAPCHE) website provides a list of all the institutions and their websites.12 Of course, the constant movement among institutions means that this list will continue to fluctuate. For ease of organization we divided the institutions according to the following basic regions: Africa, Asia—Middle East, Asia—Northeast, Asia—Southeast, Asia—South, Europe (including Russia), Latin America (including the Caribbean), and Oceania. This article draws upon these research findings and additional data to explore how to understand global Christian higher education better in light of important themes that currently influence higher education as a whole and Christian education in particular.

Nationalization and Secularization: Common Themes in the Global 3History of CHE

The Christian origins and later secularization of higher education in North America and Europe are well known.13 Yet, the creation and secularization of Christian universities also occurred in other global contexts, and in some cases, institutional secularization did not always occur. While we need a global history of Christian higher education, a review of the institutional histories of the colleges and universities on our list, as well as the history of global Christian higher education in general, reveals a couple of important themes related to the nationalization and secularization of Christian higher education.

In the global context, it remains important to distinguish between the two terms. As Hans Kohn, the well-known scholar of nationalism, observed, “Nationalism is a state of mind in which the supreme loyalty of the individual is felt to be due the nation-state.”14 This “state of mind” could also apply to the mission and culture of an institution. By “nationalization of universities,” I simply mean the phenomenon whereby leaders change a university’s governance, purposes, curriculum, and culture to make the interests and ideology of the state the foremost corporate identity of administrators and students outside of the university, certainly more important than the interests and theology of the Church.

While nationalization often contributes to secularization, it does not necessarily entail secularization. By “secularization,” I mean the removal of Christianity from a university or college’s mission, governance, public rhetoric, membership requirements, curriculum, and ethos (for example, worship).15 The reason nationalization does not entail secularization is that nation-states may have an official state church. Consequently, Christianity is often still supported at these universities as evidenced by the fact that many nationalized universities may continue to sponsor theology departments and favor Christianity in other ways.

In the global context, both nationalization and secularization should be understood as political processes. In other words, secularization is not a “natural and inevitable historical process,” but instead is something akin to a political revolution.16 If one examines particular cases, Christian higher education declined or died, not because it followed some sort of natural sociological pattern, but because it suffered the consequences of the actions of political and intellectual actors who led revolutions that ultimately led to the demise of Christianity’s influence in many institutions.

Two basic types of political secularization have occurred, our studies show. The first type was the product of political revolution, and it resulted in the abrupt demise of Christian universities, such as occurred in France after its revolution 17 and in Eastern Europe18 and China19 after communist revolutions. In these cases, Christian higher education was forcefully nationalized and secularized within a short period of time. The second type of political secularization involved a two-part process. First came the gradual nationalization of the universities, during which time the universities were considered to be both Christian and national institutions, but over time national purposes took precedence. One British parliamentary critic of the Christian nature of Oxford University in the 1800s expressed a typical attitude: “Oxford ought to be a national institution but is bound hand and feet by the clergy of one sect.”20 Thus, national leaders increasingly required their older, more prestigious universities to fulfill a nationalist agenda. The secularizing intellectual revolution stimulated by the Enlightenment helped to undergird this national vision, but state power made the changes happen.

These developments happened worldwide, albeit at different times. They occurred in Western Europe and Latin America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries21 and in Africa22 and parts of Asia in the twentieth century. In Africa, Asia, and Latin America, we see a common pattern. Christian groups, particularly religious orders or mission societies, come to or arise in a territory and start a school for basic education and theological training. The institution grows and adds fields of study. After the institution blossoms into a university or a specialized professional or technical institute, the state, for a variety of reasons, nationalizes it. The particular religious sponsor, in the eyes of political leaders, increasingly seems divisive, sectarian, or oppressive, since the universities now have a broad mission to serve the whole nation. Enlightenment-inspired secular rationalism seems like a neutral common basis that avoids sectarian rivalries in a national institution. Therefore, leaders insist that the Christian identity must be discarded or moved to the margins. This argument was often bolstered by secular-minded intellectuals who sought liberation from religious identities, communities, and ideas.

This secular revolution, while tremendously powerful, was not always inevitable or thoroughgoing, and its effects have varied by the nature of the predominant Christian tradition involved. Older Catholic universities that proclaim a Christian identity have survived in many places, such as Belgium, Colombia, Italy, the Philippines, and Venezuela, largely because of the independent strength and cultural authority of the Roman Catholic Church. Furthermore, in Brazil and Eastern Europe, a period of social and political “recatholization,” after an earlier period of secularization, allowed for the creation of newer Catholic universities as well.

In contrast to the Catholic universities, Protestant universities appear to be much more susceptible to nationalization and secularization. Protestants’ decentralized organization and unstable communal solidarity make them less able to withstand pressures to conform their institutions to nationalizing norms. Not one Protestant-founded university anywhere in the world that was started before 1817 still proclaims a Christian identity, and many have become secular in much shorter order. Reformed or Presbyterian institutions are good examples of this worldwide trend. Presbyterian/Reformed universities on virtually every continent have been nationalized and many others, even if remaining independent, have secularized. Prominent examples include MacKenzie University in Brazil, Yonsei University in South Korea, the Free University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, Potchefstroom and Stellenbosch universities in South Africa, and Princeton and Rutgers universities in the United States. Forman Christian College in present-day Pakistan provides a fairly recent example. Started by a Presbyterian missionary in 1864, the college grew to become one of the most prestigious private colleges and it educated many Pakistani national leaders. In 1972, however, the college was nationalized by the Pakistani government.23 Still, even for Protestant institutions, secularization comes in various shades and degrees, which vary by region. The oldest Protestant college that still claims its Christian identity is not in Europe or North America; it is Church Missionary Society College in India (f. 1817). India’s approach to religious pluralism within a modern secular state has evidently been much less hostile to religious institutions.24

The Eastern Orthodox Church proves to be an odd case in that it has never overseen a university that secularized mainly because it only started establishing universities in the twentieth century. Universities considered “Orthodox” by some historians, such as the early Russian universities, were always controlled by the government and not the Orthodox Church.25 The oldest Eastern Orthodox colleges or universities started in India. Eastern Orthodox universities never existed in Europe until the mid-twentieth century, and only after the Soviet Union fell did two Eastern Orthodox universities emerge in the traditionally Orthodox territory of Russia.26

The Present: Christian Higher Education in Light of Current Trends in Higher Education

Massification

Despite the nationalization and secularization of Christian universities throughout the world, a steady pattern of institutional growth has always occurred in areas such as Africa, Asia, post-communist Europe, and Latin America.27 Much of this growth, however, merely draws upon the tremendous increase in the number of students attending higher education around the world, a phenomenon scholars call “massification.”28 The following table indicates the percentage of students Christian higher education institutions educate in each country. In a few countries, the enrollment numbers are incomplete due to the lack of information about student enrollments at specific institutions (as indicated by a *).

In only five countries are fifteen percent or more of students educated in Christian institutions (Papua New Guinea – 39%; Nicaragua – 24%; Belgium – 25%; Chile – 15%; Kenya – 15%). Thus, the reality is that while Christian higher education used to dominate higher education in Europe, North and South America, and China, in almost every country in which it currently exists today, it is only a small minority in a system dominated by secular institutions.

Of course, in many countries this small minority market is still significant. In nine other countries Christian universities enroll between ten to fourteen percent of the student population (Angola—11%; Columbia 10%; Dominican Republic—10%; Ghana—10%; Lebanon—14%; Malawi—10%; Philippines—10%; South Korea—10%; Taiwan—10%; and Uganda—12%). The tremendous growth of Christian higher education in Africa is demonstrated by the fact that almost half of the countries in this category are from Africa. All the other countries benefit from the presence of large Catholic universities.

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Africa)2930

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Northeast Asia)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Middle East)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (South Asia)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Southeast Asia)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Europe)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Oceania)

Number and Percentage of Students in Christian Higher Education (Latin America)

The data also reveals that despite the growth of Christian higher education in various parts of the world, much of this growth merely filled the niche in the Christian university market that had been absent. For instance, while a number of new institutions have come into being in Eastern Europe within the past two decades, Christian institutions still do not educate more than 4% of students in any of these countries. Moreover, the legacy of communist oppression of religion still can be seen institutionally. While many Eastern European countries are now more religious than Western European ones,31 Western Europe still exceeds Eastern Europe in the percentage of students attending Christian colleges or universities. Similarly, while South Korea and Nigeria have experienced tremendous growth in the number of Christian higher education institutions, these institutions still only educate 10% of the country’s students in South Korea and only 2% of students in Nigeria. Thus, while Christian higher education continues to grow in these areas, it appears to have only attracted a small percentage of the overall college population.

Privatization and Access

Christian universities started before the development of the private-public dichotomy that evolved in America and is now used to distinguish between two types of universities around the world.32 In fact, while today we call Harvard, Yale, and Princeton private colleges, they started as public colleges (in the same way that the church was a public institution). “‘Public’ referred simply to the minority who because of rank, land ownership, or other status had a part in running society.”33 As the university grew out from the European context, the European model was initially followed in most areas (such as North America, Latin America, and the Philippines). For example, the Latin American universities were partnerships between the church and the state, although the state usually had the upper hand in most power struggles.34

The rise of the pluralistic, religiously neutral, and secular nation-state would change this context in two ways. First, as mentioned above, as many nation-states cast off old religious establishments and became religiously neutral or hostile to religion, they also increased their control over universities. In these contexts, universities that had been partnerships between the state and the church were either forcefully secularized (for example, in France, Russia, China) or gradually secularized (as in much of Western Europe and Latin America). In addition, states funded fewer and fewer religious colleges directly, because many of them stopped supporting an established church. New colleges or universities were seen as serving the politically-defined population and not a particular church.

Second, churches recognized that where possible they must build their own privately-funded universities in order to sustain Christian higher education. This pattern emerged particularly in the United States, but it would soon spread to other parts of the world. For example, Latin American intellectuals and national leaders joined together in the nineteenth century to secularize the universities and expel religion. Levy recounts: “Clerics were often purged from the professoriate; faculties of theology were closed…. The national universities generally became the State’s higher education arm.”35 In the late nineteenth and twentieth century, the Catholic Church responded by creating private universities in various countries (such as the Catholic University of Chile, 1888; Catholic University of Peru, 1917; Pontifical Bolivian University, 1936; Catholic University of Ecuador, 1946). In addition, in colonial outposts in Africa and Asia, the state did not fund educational institutions so the Church began numerous colleges and universities as part of its mission efforts. In these cases, a church or a particular mission group helped start some of the first colleges or universities in a country while the government gave permission or perhaps land but did not found or fund the institutions. The development of Christian higher education in India provides an example. Until 1815, the English East India Company banned all private enterprise in the Company’s territories. After that ban was lifted in 1815, Christian missionaries helped start CMS College (1817), Bishop’s College (1820), Scottish Church College (1830), and Madras Christian College (1837), institutions that have kept their Christian identity to this day and are older than the oldest Protestant institutions in North America that have kept their Christian identity.36

Today, the privatization of Christian higher education is the dominant pattern. According to our database, only 7% of Christian universities receive the majority of their funding from the state (see Table 8). These institutions are in England, Hungary, India, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia. Furthermore, only 15% directly receive additional funding from the state and the majority of these institutions are in India. In contrast, most global Christian universities are now privately funded and will likely remain so in the near future. In places where Christian universities are growing the most, it is largely due to new freedom for privately-funded religious universities. Thus, Christian universities prosper in countries that allow a large degree of privatization (such as Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, India, and Nigeria) while they are virtually nonexistent in countries with funding or legal structures that disfavor the creation of private universities (such as Austria, New Zealand, United Kingdom).37 The result is that the fortunes of Christian higher education will largely rise and fall with the freedom and prosperity of private higher education in countries around the globe. Of the 68 Christian universities started since 1995 (44 of which began in Africa), only four received some sort of government funding. Even in countries, such as India, where Christian colleges receive government support, an increasing number of the new institutions are private institutions.38 In many regions this reality poses a distinct disadvantage to Christian institutions when it comes to academic prestige. What should be noted, especially for North American readers, is that while older private universities in North America may be more selective and prestigious, most private institutions around the world are relatively new institutions that serve a wider audience and are not considered as prestigious.

Furthermore, this reality also means that global Christian higher education will always struggle to address another global trend in higher education—inequalities in access. Despite the rise in the number of students attending higher education, the privileged classes have maintained an advantage when it comes to access to higher education.39 Private Christian institutions, which by necessity require additional tuition than state-funded institutions, will always have difficulty addressing this problem. The few that do, such as some particular Christian institutions in India that make outreach to lower classes part of their central mission, will be able to do so due to aid from the state. Still, these institutions enjoy the freedom that comes from being private (although the exact nature of freedom given to different institutions varies tremendously from country to country).

Globalization

Globalization is identified by scholars as another important trend influencing higher education around the world. Philip Altbach defines it as

the reality shaped by an increasingly integrated world economy, new information and communications technology (ICT), the emergence of international knowledge network, the role of the English language, and other forces beyond the control of the academic institutions.40

Three things about this globalization are of particular importance for Christian higher education institutions. First, global networks have suddenly made it possible to be aware of the numerous Christian institutions due to the World Wide Web. This study reveals that within this network (perhaps a weakness of it), if an institution does not exist on the Web, it is not considered to exist. For good or bad, an institution’s virtual presence and representation define itself.

Second, an advantage of this global awareness is that regional and even global alliances among Christian universities are more possible than ever. Whereas partnerships formed on the basis of denominational affiliation are still important,41 other forms of regional and global alliances are starting to take place in ways similar to the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities in the United States. An older example of this kind of partnership is the All India Association for Christian Higher Education, while two newer groups are the Association of Christian Colleges and Universities in Asia and the International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education (IAPCHE).

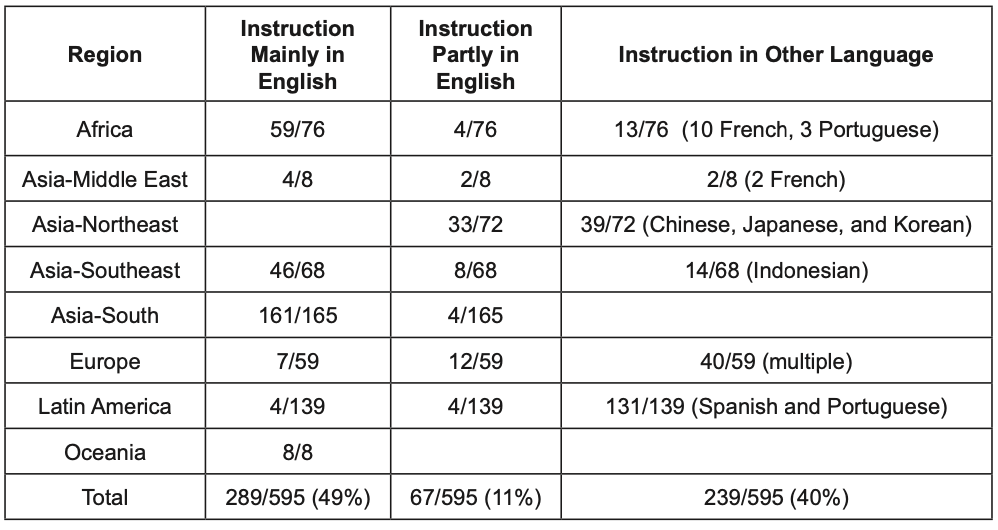

Finally, the role of the English language in fostering this global dialogue has become vitally important. As Table 9 reveals, almost half of the Christian colleges and universities outside of North America give instruction in English (the vast majority of these being in India and the Philippines) and another 11% of them give some instruction in English. Moreover, over three-fourths (76%) of Christian institutions outside of North and South America give instruction in English. The importance of English for new institutions in Africa is particularly noteworthy since Africa has shown the greatest growth in the number of Christian institutions over the past two decades. In this respect, Christian institutions reflect Altbach’s point that “the rise of English as the dominant language of scientific communication is unprecedented since Latin dominated the academy in medieval Europe.”42

Professionalization

Another global trend influencing education concerns what may be labeled the professionalization of the university. Altbach observes, “While it is difficult to generalize globally, the mission of most countries today is to teach less of the basic disciplines and offer more in the way of professional programs to a far wider range of students than in the past.”43 While the state plays some role in this trend, private schools in particular are often linked to commercial or soft technical fields (for example, accounting and IT rather than math and engineering) that are cheap to teach and promise immediate salaried jobs. Consequently, they reduce investment in libraries, labs, cultural offerings, community service, and research.44

To what degree is CHE, especially since the vast majority of it is now privately funded, participating in the reduction of general education and the liberal arts and focusing on professional education? Part of the answer to this question can be discerned from examining the nature of the new universities being started. There is clearly a new addition to the old pattern of how many Christian institutions were formed. In the past, a large percentage of Christian universities would often start as seminaries, Bible colleges, or theological institutions. They would then expand to offer other majors. Since these institutions were birthed in the liberal arts, they continued to emphasize them. While this old pattern still occurs, a new pattern has also become more pronounced, particularly in Europe. New Christian institutions are starting by offering practical professional majors, because of the specific needs in these fields and the financial benefit of focusing upon high-demand professional fields. One finds this trend particularly in countries in Western Europe (such as Germany, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom).

Yet, an overview of the majors of institutions found in the database of global Christian higher education reveals that around the globe, a significant minority of these new institutions, while clearly emphasizing practical professions that can help the local population (for example, many of the new institutions have business, economics, or technology majors), also provide liberal arts majors and service-oriented professional majors. In other words, they may have a major interest in commercial/technical fields, but a significant majority also offer majors in theology, philosophy, and languages that serve the Church or teaching, social work, nursing, and economic development that focus on serving the common good of the community.

Consider the 68 Christian universities started since 1995. As mentioned earlier, 44 of these institutions originated in Africa. All but five of these institutions provide a major in business, management, or commerce. Over half (25) also provide majors in some kind of information technology or computer science. Still, many of these institutions focus on the helping professions. Twelve offer education degrees, 10 offer degrees in the health sciences or nursing, 10 more offer degrees in agriculture and nine offer law degrees. Thus, while the kind of practical vocational focus that characterizes the new wave of private institutions of higher education exists, these Christian institutions also offer majors that encompass fields normally considered helping professions. In addition, 21 still provide majors in theology, 23 have some sort of science major, and 17 have an arts major beyond theology.

The other new universities outside of Africa evidence a similar pattern. Sixteen of the 24 offer business majors and 10 offer some form of computer degree. Helping professions are scattered throughout (five offer nursing, three offer social work, and five offer education degrees). Interestingly, only seven offer theology degrees, but 16 offer some major in the arts. In sum, without the state assisting with the budget of these new Christian universities, a significant minority are still committed to offering higher education in what are considered service professions and the liberal arts. In this respect, the broad mission of the Church still shapes their educational vision.

Future Opportunities

We should not despair when we hear the voices of the secularization prophets (which thankfully are much fewer). The massive growth of higher education and the increasing space created for private education have established opportunities for the growth of global Christian higher education. Nonetheless, we should be sober about the realities facing Christian higher education around the globe. Christian higher education is and will likely remain for the foreseeable future a minor segment of higher education in almost every country, largely privately funded, within a global higher education system that is largely governed, funded, and directed by secular nation-states, professional societies, and elites who seek agendas that may, indirectly or directly, undermine the central mission of Christian higher education.

So what can the leaders of global Christian universities do to strengthen their institutions in light of this context? They need to continue to focus, first, on building a positive vision instead of taking a defensive posture toward the culture. The best defense, football strategists are wont to say, is a good offense. Even so, they will need to think creatively and redemptively about how to deal with the particular threats of a fallen world. The following section explores some possibilities.

Unique Missions and Not Unique Forms

North American Christians have sometimes tended to see the liberal arts col-lege as the ideal institution for Christian higher education. As a result, there are very few Christian research universities and hardly any Christian community or technical colleges in the region. When considering the global context, however, Christians need to think more creatively about the various forms their institutions can take. What does need to be retained, however, is the view that Christian universities set themselves apart when they conceive of their mission in light of the overarching Christian story. Therefore, they must focus upon developing humans made in God’s image for Christ and Christ’s kingdom and not merely citizens for this world or professionals for jobs. This focus requires asking the question of how they can participate in God’s creative and redemptive work in the multiple types of universities and multiple levels of the university.

Creatively Incarnating Christian Distinctiveness

The rush to meet the needs produced by massification or the restrictions posed by state partnerships will continue to prove a challenge to creating programs that focus on the holistic development of students. Christian education has proven and must continue to prove itself different in this area. While the findings mentioned earlier indicate that Christian universities have continued to develop majors in other fields beyond professional vocations, it should also seek the holistic education of students in professional programs.

General education. In most cases, global universities outside of North America offer no such thing as general education. Christian universities that seek to educate students to love God holistically provide a vibrant counter-cultural witness when they require a general education or core curriculum that focuses upon educating students to be fully human.45 For instance, this would mean that the moral education provided in such courses would focus not only upon providing technical knowledge of ethical theory or even certain basic moral competencies in ethical reasoning. Instead, it would set forth and seek to incarnate a holistic vision of human flourishing grounded in Christ and the vision of the Kingdom of God.

The range of majors. New Christian universities usually offer majors that meet particular needs in society. North American Christian academics often belittle a jobs-oriented focus of higher education in favor of a liberal arts model, but they forget that a liberal arts education was historically designed for the person of means with the time and money to engage in this form of well-rounded education. In many places in the world, the Christian community must focus upon providing education that can lead to a job. The key for Christian institutions in this situation is to provide a wider range of vocational options—not merely to focus on business and computing but also on teacher education and the full range of helping or service professions beyond teaching.

Majors or professional degree programs that incorporate broader (including faith) perspectives. In light of the professional/technical emphasis of most global universities, Christian universities will stand apart by offering additional courses, as well as instruction within the basic courses in the field, that address larger theological, philosophical, and ethical issues. In other words, they need to incorporate the liberal arts into more professionally focused forms of education. Most science and social science majors never study the historical, philosophical, sociological, or ethical dynamics that shape their disciplines. In this respect, the Christian professional societies, such as the Christian Engineering Society,46 that have developed in North America need to be fostered in other global contexts because these societies have focused on curricular and worldview-driven issues within the contexts of professional education. Such societies can encourage an educational conversation that widens the scope of typical professional education to include theological context, holistic ethical concerns, and how one’s professional life fits into a larger vision for human flourishing.

University administrators need to reinforce these conversations by making room for general education units within professional degree programs. Even while the Bologna Accords seem to be pushing the world toward ever-narrower specialization within three-year degree programs, there are some interesting counter-moves afoot. For example, the universities in Hong Kong are expanding to a four-year bachelor’s degree calendar in order to add general education requirements.47 Christian universities should applaud—and emulate—such moves.

Student Life. Global universities tend to neglect the holistic needs of students by offering very little when it comes to student life programming and oversight. Yet, we know from research done in the United States that much of the consolidation of students’ undergraduate learning happens outside of the classroom and in students’ co-curricular experiences.48 On the global scene, where so many universities are strictly commuter institutions that give little attention to how students put living and learning together, global Christian universities could benefit greatly and provide a stark counter-cultural witness by investing time, creativity, and resources into the student life side of education.

Broader Christian Partnerships

While various Christian denominations have sustained supportive partnerships with universities for a long time, other forms of partnerships have only recently developed and these too need more support. Many of these new Christian universities need wisdom as they think through how to integrate faith and learning. There are some global partnerships that have emerged, such as the International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education (IAPCHE), which is linking Christian universities and educators worldwide and providing programs and resources for institutional and faculty development. These kinds of partnerships can help universities think about issues of faith and learning at multiple levels.

Christian universities also need to develop or to support existing regional fellowships of Christian universities such as the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities and the Lily Fellows Network of Church-related Colleges and Universities in North America, the Asian Christian Universities and Colleges group in East and Southeast Asia, and the All India Association of Christian Higher Education. In addition, IAPCHE is developing regional partnerships in areas currently lacking structures, such as Europe, Africa, and Latin America. These kinds of partnerships will prove particularly important to sharing global ideas regarding the integration of faith and learning that can stimulate out-of-the-box, creative thinking.

Finally, there is a greater need for “bilateral” global partnerships between older and more settled Christian universities and newly founded ones in dynamic settings of need. The University of Notre Dame provides a positive example. The formation of the University of Notre Dame Australia (f. 1989) marked the beginning of the first Christian university in Australia, and this university would not have been possible without the help of the University of Notre Dame in the United States. As one chronicler of the history wrote: “Indeed, the early NDUS commitment and involvement was the perhaps most important single factor in causing this project to proceed beyond the feasibility study stage.”49 Notre Dame has participated in similar global partnerships with young Eastern European Catholic universities. Protestants have not been nearly as successful in this endeavor, although some exceptions exist.

Addressing the Threats

The domineering state. One of the major threats to Christian universities around the world is increasing centralized government control of education. As our data and the recent global history of Christian higher education reveals, Christian universities appear to flourish best when a pluralistic system of higher education is fostered. In recent years, centralized state systems have responded to the great demand for higher education by awarding university charters to non-state institutions. But even where this new pluralism has emerged, state systems are reasserting their power. And in some nations, state command and control impulses are still very strong. Christian universities will need to form partnerships with other non-governmental institutions to protect their freedom as they seek to create and sustain a robust civil society. Christian university leaders should remain wary of government funding since it is linked to government control, and they should continue to take full advantage of laws allowing for the creation of private universities. While public funding is not always detrimental to the survival and integrity of Christian universities, such funding usually comes with particular limitations upon programs or hiring. Protestants have been notoriously susceptible to losing their institutions to these powers and dominions, and there is a reason the vast majority of vibrant Protestant Christian universities are largely privately funded.

The Market. The expanding market for higher education has fed the global growth of Christian higher education, but the current higher education boom will not go on indefinitely, particularly in areas such as Russia and Europe where the population declines and demand for higher education slackens. Market pressures may pose tremendous threats to the unique vision and mission of Christian universities. For instance, extra-general education classes in theology, Bible, and ethics or required chapel classes may add to the cost or time of obtaining a degree in some contexts, and thus prove a hindrance to the expansion of one’s enrollment. Furthermore, market pressures may induce some institutions to expand revenue-producing majors such as business and technology at the expense of offering courses in theology, Bible, philosophy, or ethics. In addition, hiring full-time staff that supports the Christian mission of the institution may be seen as financially burdensome, especially in contexts where the competitors work mainly with cheaper part-time instruction. In these cases, Christian leaders will sometimes be faced with the choice between being faithful to what is best for their Christian educational mission or fostering the survival of the institution at the expense of either the Christian mission or academic integrity. Christian leaders must remember that institutions are not people. The death of an institution can lead to the rebirth and resurrection of something quite different and more lasting.

Christian Unfaithfulness. Fundamentally, the above two threats only prove effective when Christians succumb to their lures. The most fundamental threat facing the Christian university is when Christians lose their way and substitute other loves such as academic prestige, love for knowledge or humanity, or even institutional survival for their first love for God, God’s truth, and God’s reign. If history teaches us anything about sustaining academic institutions designed to further the love of God with our minds, desires, and actions, it proves how incredibly difficult it is to maintain these priorities over the decades. Like unfaithfulness in marriage, academic unfaithfulness becomes pervasive and ultimately fatal. Only by God’s pervading and prevailing grace can Christian institutions ultimately resist this threat. They need communities of the faithful to uphold them in prayer, support them with students and funds, and hold them accountable to their original aims and purposes.

Redemptive Engagement

Sustaining the redemptive work of Christian universities requires a vibrant connection to Christian communities. In Africa, Asia, and Latin America, we see denominations eagerly encouraging the startup of new Christian universities. And the Roman Catholic and Adventist communities of faith have built extensive global networks of colleges and universities by emphasizing first and foremost their service to Christ and the Church, and most notably in preparing graduates for vocations, whether the priesthood in the Catholic context, or healthcare and teaching amongst the Adventists. These vocations as a matter of course serve the common good, but only as they “seek first the Kingdom of God.” By contrast, Protestant colleges and universities have demonstrated a continual tendency to be captured by what for Christians must be more contingent and secondary academic goals, such as academic excellence or national service. It also appears that while specific Christian traditions continue to encourage the startup of universities, the amount of support and attention given to universities by denominations may be diminishing.50 In this respect, we may also need new creative ways of thinking. What appears to be growing is the role of megachurches and megapastors in starting universities as illustrated by the growth of Oral Roberts, Liberty, and Regent universities in the U.S., Central University College in Ghana, and Hansei University in South Korea. Perhaps megachurches may become natural partners for Christian universities in their vicinities.

While global partnerships will help with the sharing of ideas, Christian universities need to think about the generation of ideas as well. To be healthy and sustainable, they cannot continue to rely only on the borrowing and perhaps retrofitting of ideas issuing out of secular intellectual frames and factories. Ideally, there should be at least one or two Christian universities in a region that are devoted to producing postgraduate studies and students. They can become centers for producing discoveries, ideas, and cultural products that are animated by Christian vision and intelligence. It would be much easier for graduates from a Christian university in Lithuania to attend a Christian research university in Hungary to study how to produce creative and redemptive forms of scholarship with relevance for that region than either to re-fit what they have learned at a nearby secular university or at a Western European Christian university. Similarly, a Christian research university located in West Africa would be much better equipped than a North American one to supply the surrounding region with creative and redemptive scholarly ideas relevant to the local context. We need to have some of these young Christian universities develop into successful research universities and take leadership in fields of scholarship. Christian universities currently cover the imparting of knowledge with growing competency, but they need to have some sister institutions that become adept at producing knowledge as well. Without them, the ecosystem of Christian higher education is incomplete and perhaps not sustainable.

Conclusion

If Christians scholars are to begin thinking about themselves as first and foremost followers of Christ and not servants to the profession, nation, or some other master, we must begin to think globally about education and our professions with a focus upon the Christian Church’s story. We must learn and tell the story of Christian higher education from around the globe, something we have not yet done as evidenced by the fact that a global history of Christian higher education does not exist. We need to tell the story of our educational saints who began small Bible schools that have turned into institutions that serve the church and humanity in tremendous ways. Of course, we must also tell the tragic story of how the world works itself into our best creations and distorts them. Finally, North American institutions in particular should think strategically about how they can partner with these institutions around the world to make our education more diverse and global, so we can prepare ourselves among this kingdom and the coming kingdom when we celebrate with Christ among all tribes, tongues, and nations.

Cite this article

Footnotes

- For scholarship about the growth patterns of global Christianity, see Douglas Jacobsen, The World’s Christians: Who They Are, Where They Are, and How They Got There (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2011); Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, rev. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); Philip Jenkins, The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). For scholarship about the global growth and nature of Christian higher education, see Perry L. Glanzer, Joel A. Carpenter, & Nick Lantinga, “Looking for God in the University: Examining Trends in Global Christian Higher Education,” Higher Education 61.6 (2011): 721-755; James Arthur, Faith and Secularisation in Religious Colleges and Universities (London: Routledge, 2006); and Joel Carpenter, “New Christian Universities and the Conversion of Cultures,” Evangelical Review of Theology 36.1 (2012): 14-30.

- Perry L. Glanzer, Joel A. Carpenter, & Nick Lantinga, “Looking for God in the University: Examining Trends in Global Christian Higher Education,” Higher Education 61.6 (2011): 721-755.

- For one version of this database, see International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education, http://iapche.org/wordpress/?page_id=275 (accessed January 2, 2013).

- For a summary of the recent global trends in higher education in general, see Philip G. Altbach, Liz Reisberg, and Laura E. Rumbley, Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution (New York: UNESCO, 2009). For a discussion of global secularization trends in faith-based higher education, see Arthur, Faith and Secularisation in Religious Colleges and Universities.

- Glanzer, Carpenter, & Lantinga, “Looking for God in the University.”

- or a contemporary example, see Merrimon Cunninggim, Uneasy Partners: The College and the Church (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994).

- This definition relies upon Robert Benne’s typology developed in Quality with Soul: How Six Premier Colleges and Universities Keep their Faith with their Religious Tradition (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 48-65. I should note that our definition excluded universities that merely recognize a historic connection to a church, denomination, or Christianity (for example, Oxford University and Yale University). In addition, we excluded colleges that are members of religious associations of colleges and universities due to these historical connections but that do not identity their religious identity as influencing their mission or as being central to their identity (for example, many of the universities listed on denominational association websites). Admittedly, this approach still results in some difficult borderline cases. We also excluded from our list state-funded universities that exist in nations with a state church that do not identify themselves primarily or equally as Christian institutions. For instance, state churches still exist in Denmark, England, Greece, Iceland, Malta, Norway, Scotland, and various cantons of Switzerland, and close links with particular churches exist in many other countries. Nonetheless, both the churches and Christian perspectives play only a limited role in the life of the national universities in these countries. Moreover, universities in these countries identify themselves first and foremost as national institutions and not as Christian institutions (although they may sponsor a theology faculty linked to a particular church).

- Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2013). Classifications, http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org (accessed January 2, 2013).

- See, for example, the institutions found listed as Colleges and Universities of the Anglican Communion, http://cuac.anglicancommunion.org (accessed January 2, 2013), and the International Federation of Catholic Universities, http://www.fiuc.org/cms/index.php?page=homeENG (accessed January 2, 2013).

- For specific information about our method and the various types of data gathered, see Glanzer, Carpenter, and Lantinga, “Looking for God in the University,” 726-727.

- For tables and analysis pertaining to the historical and denominational breakdown of these universities, see Ibid.

- International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education http://iapche.org/wordpress/?page_id=275 (accessed January 2, 2013).

- For example, see James T. Burtchaell, The Dying of the Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from their Christian Churches (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998); George Marsden, The Soul of American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established No Belief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Hans Kohn, Nationalism: Its Meaning and History (Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand, 1955), 9.

- C. John Sommerville provides an insightful overview of the five understandings of secularization employed by scholars. When discussing secularization, scholars may refer to the secularization of society, institutions, activities, populations, or mentalities or some combination of these five. My definition would encompass all these types of secularization within a university setting. In other words, secularization occurs when a particular college or university separates itself from church governance and financial support (secularization of institutions), drops religious requirements for entrance, and no longer requires Bible or theology and courses (activities), the faculty and students are not held to any religious requirements (populations), and scholars abandon the use of Christianity to make sense of the world and their work (mentalities). C. John Sommerville, “Secular Society/Religious Population: Our Tacit Rules for Using the Term `Secularization,’” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37 (June 1998): 249-253.

- Christian Smith, “Rethinking the Secularization of American Public Life,” in The Secular Revolution: Power, Interests and Conflict in the Secularization of American Public Life, ed. Christian Smith (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 1-96.

- Robert Anderson, European Universities from the Enlightenment to 1914 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 39-50.

- Perry Glanzer, “The Role of the State in the Secularization of Christian Higher Education: A Case Study of Eastern Europe,” Journal of Church and State 53.2 (2011): 161-182.

- Jessie Gregory Lutz, China and the Christian Colleges, 1850-1950 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971); Daniel H. Bays & Ellen Widmer, eds., China’s Christian Colleges: Cross–Cultural Connections, 1900-1950 (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009).

- V. H. H. Green, Religion at Oxford and Cambridge (London: SCM Press, 1964), 153.

- Robert Anderson, European Universities from the Enlightenment to 1914 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Daniel C. Levy, Higher Education and the State in Latin America: Private Challenges to Public Dominance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 26-65.

- Y. G. M. Lulat, A History of African Higher Education From Antiquity to the Present: A Critical Synthesis (New York: Praeger, 2005).

- Forman Christian College, “Heritage,” www.fccollege.edu.pk/about/heritage (accessed January 2, 2013). Interestingly, in 2003 the government returned the college to the Presbyterian Church of the USA. Even so, the university has remained secular in its mission and curriculum.

- Additional older Christian colleges in India include Bishop’s College (1820), Scottish Church College (1830), and Madras Christian College (1837).

- For an explanation of these reasons, see Perry Glanzer and Konstantin Petrenko, “Resurrecting the Russian University’s Soul: The Emergence of Eastern Orthodox Universities and Their Distinctive Approaches to Keeping Faith with Their Religious Tradition,” Christian Scholar’s Review 36 (2007): 263-284. See also Judith Herrin, “The Byzantine ‘University’—A Misnomer,” in The European Research University: An Historical Parenthesis, eds. Kjell Blückert, Guy Neave and Thorsten Nybom (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

- Ibid.

- For some analysis of the historical growth patterns see Glanzer, Carpenter and Lantinga, “Looking for God.”

- Philip G. Altbach, et al., Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution, vi and 5-7.

-

The total student enrollment numbers are taken from the most recent enrollment statistics provided by UNESCO http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx (accessed 27 April 2013). The enrollment statistics were in almost all cases drawn from the classification that approximated the category we used, what UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics labels “Tertiary-type A education.” They define these institutions as “Largely theory-based programmes designed to provide sufficient qualifications for entry to advanced research programmes and professions with high skill requirements…Duration at least three years full-time, though usually four or more years.” Education at a Glance 2012: OECD Indicators (OECD Publishing, 2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2012-en. In a few cases that are starred (*), only combined tertiary-type A and B enrollment statistics were available. -

The enrollment statistics for universities were in almost all cases taken either from the websites of the institutions or the International Handbook of Universities, vols. 1-3, 21st ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). - Phillip Jenkins, God’s Continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe’s Religious Crisis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- See, for example, the International Handbook of Universities, 2010.

- Marsden, The Soul of the American University, 39.

- Daniel C. Levy, Higher Education and the State in Latin America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 28-29.

- Ibid., 31.

- The Christian College in India: The Report of the Commission on Christian Higher Education in India (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), 63-64. Interestingly, the oldest Christian col- lege in America that still identifies itself explicitly as Christian is a women’s college: Judson College, AL (1838).

- Trends in Global Higher Education, xiv.

- J. Dinakarlal, “Christian Higher Education in India: The Road We Tread,” 2012, unpublished manuscript.

- Trends in Global Higher Education, vii-viii, 37-50.

- Ibid., iv.

- See, for example, the Colleges and Universities of the Anglican Communion, http://cuac.anglicancommunion.org/ (accessed January 2, 2013), and the International Federation of Catholic Universities, http://www.fiuc.org/cms/index.php?page=homeENG (accessed January 2, 2013).

- Trends in Global Higher Education, iv.

- Ibid., x.

- Daniel C. Levy, “The Unanticipated Explosion: Private Higher Education’s Global Surge,” Comparative Education Review 50.2 (2006): 217-240; Daniel C. Levy, “An Introductory Global Overview: The Private Fit to Salient Higher Education Tendencies,” PROPHE Working Paper #7, Program for Research in Private Higher Education (University at Albany, State University of New York, 2006).

- For an example of what this might look like, see Perry L. Glanzer and Todd C. Ream, Christianity and Moral Identity in Higher Education (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Christian Engineering Society, http://www.calvin.edu/academic/engineering/ces/ (accessed January 2, 2013). See also the list of other professional societies in Todd C. Ream & Perry L. Glanzer, Christian Faith and Scholarship: An Exploration of Contemporary Developments (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report. Jossey Bass: San Francisco, 2007), 80-81.

- Janel Marie Curry, “Cultural Challenges in Hong Kong to the Implementation of Effective General Education,” Teaching in Higher Education 18.2 (2012): 223-230; David Jaffee, “The General Education Initiative in Hong Kong: Organized Contradictions and Emerging Tensions,” Higher Education 64.2 (August 2012): 193-206.

- Alexander W. Astin, “Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education,” Journal of College Student Development 40.5 (1999): 518-529.

- Peter Tannock, “The Founding of the University of Notre Dame Australia,” broome.nd.edu.au/university/history.shtml (accessed May 2, 2012).

- See, for example, Perry L. Glanzer, Jesse Rines, and Phil Davignon, “Assessing the Denominational Identity of American Evangelical Colleges and Universities, Part One: Denominational Patronage and Institutional Policy,” Christian Higher Education 12.3 (2013): 181-202.