Today, I want to discuss a second skill that I think should be a major component of advanced forms of Christ-Animated learning, yet I also rarely see it employed. For example, in the five years of editing this blog, I can only recall a few posts on this topic. Every Christian student at a Christian university, by the time they graduate, should be able to evaluate their academic discipline within the Christian story. Most cannot. In fact, I find professors often cannot undertake this type of analysis. This post explains what I mean and how to teach your students to engage in this activity.

Placing One’s Discipline in the Christian Story

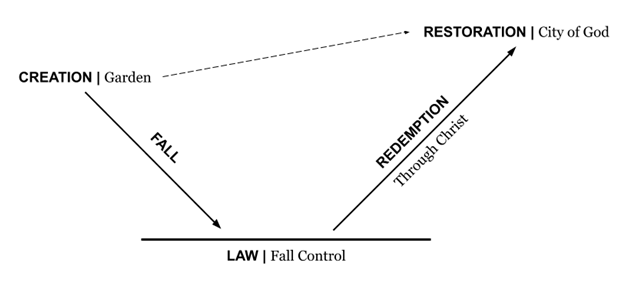

As mentioned yesterday, I find this drawing a helpful way for students to think about the overall arc and theological themes of the Christian story.

To then place one’s academic discipline within the Christian story, I ask several thought questions that I have listed below.

To then place one’s academic discipline within the Christian story, I ask several thought questions that I have listed below.

1. What about your discipline reflects God’s goodness derived from God’s good creation? What does it mean to steward this discipline well? Would this discipline have existed without the Fall? In what form?

Take, for instance, an academic discipline that is often considered a difficult one to engage in Christ-animated learning: accounting. What about accounting reflects God’s good creation? If the Fall had not occurred, would we still have needed to develop accounting? What does that tell us about the created good that accounting helps us perform? I believe that accounting would still have developed in an unfallen world as humans discovered numbers, invented money, built and organized culture, and learned to steward both God’s creation and human culture (i.e., the things that humans create—which includes money). Furthermore, in light of the creation mandate or commission that God gives us in Genesis 1:28, we would still have developed advanced forms of accounting and had to learn how to steward this humanly created discipline well.

2. What is fallen or reductionistic about this academic discipline?

I find I often have problems with certain defenses of the liberal arts because the authors argue that if we have all students take the liberal arts, it will automatically result in their increased understanding of truth, goodness, and beauty, as well as their flourishing. For instance, I recently read an essay by a scholar and practitioner of music, one of the original elements of the liberal arts quadrivium, in which he argued that music can be a force for good, without acknowledging that it has also been used for evil. We should not neglect the fact that every discipline, including the disciplines in the liberal arts, has and is fallen. Moreover, in every liberal arts college, the disciplines can be taught in ways that morally deform students. For example, I would not trust the moral formation of students from the top twenty-five liberal arts colleges in America. The fallen elements of any discipline, including the liberal arts, need to be identified. The same is true for the profession associated with that discipline.

I suggest that the easiest way to do this is to gather together a group of 50-some-year-old practitioners of this discipline, because they are the types who like to sit around at lunch and complain. Then ask them two simple questions: What is wrong with how (X, e.g., accounting, biology, history, music, etc.) is practiced today? What is wrong with (X’s, e.g., accounting’s) professional society or academic journals? That would be the start of this kind of critical analysis.

Now, the problem with many academics today is that they prefer to dwell on these questions without considering the first one about creation-based norms or moving on to the next one about redemption. They are great at deconstructing and pointing out sin in people, institutions, academic disciplines, scholarship, or structures, but they offer little creative thinking about recreating or redeeming these entities. These are the types of academics who compose whole books examining problems and then end with two pages of idealistic suggestions that show a tremendous lack of theological imagination and acquaintance with reality.

3. How can one draw upon Christ and what the New Testament teaches us to redeem the discipline (i.e., reverse its fallenness)?

Christians, since they exalt Christ, know that sin, Satan, and the principalities and powers have been defeated on the cross. Christ did the work for us. Now, we are given the tremendous honor of joining with Christ in reversing the Fall throughout the world—including in our academic disciplines, or as John Milton famously articulated, “the end then of Learning is to repair the ruins of our first parents.” Figuring out how to do that under the guidance and wisdom of the Holy Spirit and other academic mentors is one of the most important things you can offer your discipline. Yet, few Christian academics progress to this level.

Fewer still can articulate to their students how to do that. Yet, I would argue that it is one of the most important things Christian academics should offer our students. The books we highlight on our website’s bibliography offer some of these suggestions for various disciplines. For instance, in my own study of the discipline of student affairs, I found some Christians doing some great work in areas such as redemptive discipline and racial reconciliation that needed greater attention, but I also saw the need for more creativity when it comes to teaching students about stewardship of the body. If your students do not leave with some basic skills and ideals regarding how to redeem their discipline or profession, you have failed as a Christian educator.

4. How might this discipline need to change in light of the Kingdom of God? How do you place your disciplinary knowledge under Christ’s Lordship?

One of the ways to cultivate the redemptive imagination to see what your academic discipline needs to be is to think about how your discipline might be practiced in the Kingdom of God. Of course, it always requires a dependence upon God. In this regard, I find the story in Mark 4:35-41 an interesting reflection on how we should see our professional competence under Christ’s Lordship. The disciples, most of whom were fishermen, could not navigate the storm by themselves. Despite their “professional” competence, they still desperately needed Jesus’s help. We should always have the same posture toward finding wisdom and help within our discipline and its storms.

Some Examples

I teach in the field of higher education, so I will use it as an example of how to undertake this process. First, I ask my students and other students what the purpose of higher education is. Almost all of them focus on self-oriented purposes such as professional competence, learning, growth, and development etc. I then ask them what a God-oriented purpose might be. Most do not know how to think theologically about higher education. To help with that, I ask my students: Would we have built universities without the Fall? Students almost always answer yes to this question because they recognize that discovering mysteries about God’s good creation and then passing this knowledge along to others would require this kind of social organization.

Unfortunately, many of them have not thought about how having a Christian anthropology and the Christian understanding of the creation mandate in Genesis 1 changes the whole purpose of the university. If we are made in God’s image to bear God’s image and steward God’s creation, then how does the university contribute to that purpose? Answering that question helps students recognize that the Christian story has a tremendous amount to say about the Christian purpose of a university and the disciplines within it.

Second, I ask students, how has/is higher education fallen? That one is easy for my students. Thus, I do not necessarily need to bring in an experienced 50-year-old administrator to tell them about it, although that also helps. For instance, I have invited the administrators who deal with faculty discipline to come into my class and talk to students about the crazy things that faculty will do (and thus they learn the way that faculty are fallen).

Third, the hardest topic for my students to contemplate is how to redeem or reverse the Fall in higher education. Since they are not experienced administrators yet, they do not yet have the imaginative skills in this area. Thus, I try to show them how they can gain them. In fact, I consider this part of any course to be the most important part.

Three approaches in particular are helpful: 1) interviewing students, faculty, or administrators about what has reversed the fall in their own professional and personal lives; 2) studying the history of higher education; and 3) studying other universities around the world, especially other Christian universities. These three things usually end up spurring redemptive ideas that students have never considered. It also works in my own life. For example, when I recently traveled to Australia, I discovered that the University of Notre Dame in Australia offered a required class on moral theology for all graduate students. I think it is an excellent idea that could be helpful at any Christian university (for more on what one might learn from Australian CHE see here and here).

These kinds of comparisons also open your eyes to what you are doing right. For instance, when I helped start the Baylor Faith and Character Survey that we have now been giving students for the past eight years, I wondered if the administration would want us to publish the results. Yet, the reality is that we have discovered a plethora of ways that our faculty and staff are shaping our students in positive ways, as well as a few key areas we needed to and did improve.

Finally, considering the end of the Christian story gives us hope. We cannot correct all the lack of stewardship, apathy, injustice, and foolishness in higher education in this life. Such a realization can lead one to despair. Yet, there is one who will address all these problems one sees in higher education. An ultimate accounting will take place. We can anticipate ultimate justice and love—even in our academic disciplines.

Well said again, Perry! I teach public health nursing to BSN students. Integrating “Fall Control” (I love your diagram) is straight forward in this discipline. BUT I buck the contemporary trend to focus on victimization, reducing humans to objects within oppressive power structures. While this certainly happens and fall control includes issues of social justice, “social justice” should never be the tail that wags the dog. Reductionistic schemas of what it means to be human are truly anti-human.

Thank you Ruby! It sounds like you have some clear ideas how how to redeem your own discipline. If you’re interested, I’d love to receive a blog post from you about how to engage in this kind of Christian thinking regarding nursing.

Such an important reminder. As a professor at a Christian university, do we always teach solidly from a Christian worldview? Sometimes, we can blur the lines and no doubt some students are asking themselves: “What in the world is he trying to do?”