This July marks the one hundredth anniversary of the most famous event in the history of American religion and science, the trial of John Scopes for teaching evolution in a rural Tennessee high school. The rookie teacher was convicted of violating a new state law prohibiting public schools “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animal.” Ironically, both the prosecution and the defense wanted a conviction. Responding to a solicitation from the American Civil Liberties Union, the Dayton school board had asked Scopes to stand trial, hoping to find him guilty so the law itself could be overturned in higher courts—a strategy that ultimately failed.

Scholars have generated an enormous literature related to Scopes in the century since it happened. Hundreds of books scrutinize William Jennings Bryan and his fundamentalist friends, but the modernist Protestants who were intimately involved with defending evolution at the Scopes trial are typically seen only as Bryan’s foil or the obvious alternative to Bryan’s folly. That is why I wrote the first book about modernist views of science and religion between the world wars: it’s high time someone took a closer look at them.

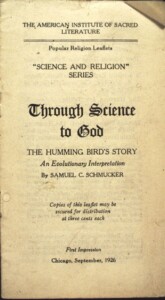

A wealth of hitherto neglected sources made this possible. Decades ago I stumbled upon a virtually unknown tract about “Science and Religion” from 1926. The author, naturalist Samuel Christian Schmucker of West Chester (PA) State Teachers College, was prominent in Nature Study, an early form of environmental education that stressed taking students outside, Under the Open Sky, to borrow the title of one of his books. He was also a nationally known popularizer of evolution in the 1910s and 1920s, especially at Chautauqua where his lectures (illustrated with lantern slides) drew the largest crowds. Two of his books were used as texts by the Chautauqua Literary & Scientific Circle, rather like a college without walls. He had been such a popular teacher that the science building at West Chester, dedicated twenty years after his death, was named for him—only to have his name removed three years ago when his strong support for eugenics became widely known on campus; one of my articles was cited in the process.

Photograph by Edward B. Davis, from the author’s collection.

In this shirt-pocket size leaflet, Schmucker used sexual selection to connect an eternally existing nature with a wholly immanent God who had not created its laws. Photograph by Edward B. Davis, from the author’s collection.

When I first saw Schmucker’s pamphlet, I could not identify the American Institute of Sacred Literature, the now-defunct entity named at the top of the front cover (above). Soon I learned it was a correspondence arm of the University of Chicago Divinity School, and eventually I knew that they had published ten pamphlets on “Science and Religion” between 1922 and 1931. The full set of authors and titles included some important names in American history: Nobel Laureate physicists Robert Millikan and Arthur Compton, theologian Shailer Mathews (who edited the pamphlet series), and the most famous liberal preacher of his generation, Harry Emerson Fosdick. All but one—physicist Michael Pupin, a Serbian Orthodox believer who was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1925—were religious modernists. In other words, the pamphlets were written by the very people whose ideas William Jennings Bryan most despised, those liberal Protestants who wanted to “modernize” Christianity by discarding biblical miracles and the orthodox creeds, in favor of the Social Gospel and vaguer notions of God that (in their view) did not conflict with modern science.

Intended to diminish opposition to evolution and to persuade Christians to adopt more positive attitudes toward modern science, the pamphlets were distributed to high school principals in every state, university campuses, scientists, clergy, and legislators. Very scarce today, the pamphlets and their history constitute a revealing window on the Protestant modernist encounter with science, adding new context for understanding Bryan and his religious opponents at the trial.

What did I learn? Bryan’s concerns about evolution and education were partly shared by the modernists, especially his view that survival of the fittest undermines human decency and morality. They also agreed with Bryan that college professors were undermining the religious beliefs of students. Where for Bryan this problem was also rooted in evolution, the modernists blamed philosophical reductionism, the view that science somehow “explains away” our humanity, since chemicals have no values and we are nothing more than pre-programmed biochemical machines. Bryan rejected all efforts to baptize evolution, while the modernists sought to base their theologies of nature heavily on evolution and modified their conceptions of God, often in radical ways—tossing divine transcendence under the bus in favor of a purely immanent god who had not created nature or its laws. Many modernists also embraced eugenics as an effective means to bring about the kingdom of God on earth through the elimination of undesirable traits and behaviors from the germline. At the same time, perhaps surprisingly, the modernists still accepted design in nature, despite rejecting the traditional Christian theology embraced by many advocates of “intelligent design” today. Finally, the modernists uncritically accepted the “Conflict Thesis” of Andrew Dickson White and John William Draper—the idea (now rejected by historians) that Christian theology has always been unable to engage science in fruitful conversation and must be discarded in order to make social and intellectual progress. For much more on each point, see the longer version of this essay at BioLogos.

Is there a middle way between Bryan’s uncompromising rejection of all forms of “theistic evolution” and the modernists’ wholesale rejection of classical theism in the name of “science”? In the culture war of the 1920s, Protestant thinkers who accepted both evolution and the Nicene Creed, as Asa Gray and others had done in the 1880s, were thin on the landscape. None of the pamphlet authors qualify, since Pupin was not a Protestant. For the person in the pew, the stark choice seemed to be Bryan or the modernists. Those with different views beyond these two were hard to hear amidst the din of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy.

We still find ourselves today in a culture war involving religion and science, and in one way it’s even more polarized. Young-earth creationism, which had no traction among fundamentalist leaders in 1925, is so dogmatically literalist that even Bryan gets criticized for betraying the Bible. A list of “compromised” evangelical leaders compiled by Ken Ham’s Answers in Genesis includes not only Bryan, but a virtual who’s who of evangelical leaders past and present: Billy Graham, Reuben Torrey, James Orr, Charles Spurgeon, Charles Hodge, B. B. Warfield, James Montgomery Boice, Gleason Archer, Bill Bright, Norman Geisler, William Lane Craig, J. P. Moreland, Bruce Waltke, and Tim Keller. They all made the mistake of interpreting Genesis differently than AiG. They did not “uncompromisingly contend for the literal historical truth of Genesis 1–11, which is absolutely fundamental to all other doctrines in the Bible.” (For more on creationism’s uncompromising tone, see my comments here.)

Nevertheless, in another way the situation has changed fundamentally. In 1925, there was no one like Francis Collins, an adult convert from atheism to evangelical faith who succeeded the outspoken atheist James Watson as director of the Human Genome Project and later headed the National Institutes of Health. Nor was there anyone like the late Charles Townes, one of the greatest experimentalists of the last century and a traditional Christian who was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for inventing the maser (ancestor of the laser). Another Nobel Laureate, physicist William D. Phillips, identifies as an “ordinary” Christian, sings in his church’s gospel choir, believes that science cannot deny miracles and affirms the bodily Resurrection. Astrophysicist Joan Centrella, a leading expert on general relativity, became a Christian early in her career and led Bible studies for her departmental colleagues. Distinguished climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe is an active member of an evangelical church in Texas, where her husband Andrew Farley is the head pastor. These names could be multiplied dozens of times. Two organizations of Christians in STEM fields, the mainly Protestant American Scientific Affiliation and the recently formed Society of Catholic Scientists, have several thousand members, most of them traditional Christians who accept evolution and some of them as accomplished as Compton or Millikan. Neither organization existed in Bryan’s day, when nearly all eminent American scientists whose beliefs are known to me were agnostics, atheists, or modernist Protestants. The contemporary conversation about religion and science is certainly subtler, broader, and deeper than when John Scopes walked into Rhea County Courthouse.

Thank you for this helpful post, Ted. I had not realized quite how polarized the science-faith conversation was in the 1920s.

Is there any evidence that some people at that time defaulted to theological liberalism or fundamentalism, despite neither being an ideal fit for them personally, because those were the only two prominent options on the table for addressing science-faith questions?