Ever since Max Weber first named the iron cage over a century ago, people have been interested in unchaining it. Christians may have a particular interest in Weber’s analysis because it points to the influence of religious values both in supporting initially, and then potentially liberating humankind from, the iron cage. Bruno Dyck, Mitchell J. Neubert, and Kenman Wong describe what the four functions of management—controlling, leading, planning, and organizing—might look if managers were liberated from the iron cage thinking. They draw on organizational learning theory to describe a process managers can follow to unchain the iron cage, and they discuss implications for management theory and practice. Mr. Dyck is Professor of Management at the University of Manitoba, Mr. Neubert is Professor of Business at Baylor University, and Mr. Wong is Professor of Business Ethics at Seattle Pacific University.

This paper builds on a century of scholarship, starting from Max Weber through to the work of contemporary management scholars. In essence, we present two different Weberian “ideal-types” of management. First, we use the term “Mainstream management” to refer to management theory and practice that is grounded in a moral point of view that emphasizes material and individual wellbeing. From a Mainstream approach, management is all about maximizing productivity, efficiency and profitability. Second, we use the term “Multistream management” to refer to management theory and practice that is grounded in a moral point of view that seeks to balance multiple forms of well-being (e.g., financial, physical, spiritual, social, ecological) for multiple stakeholders (e.g., owners, employees, suppliers, competitors, future generations).1

Weber’s influence on organization studies may be unrivaled.2 He is credited with developing many of the basic concepts of management and organization theory, and is still considered a leading moral philosopher of management.3 He also coined what has become one of the most well-known metaphors in the social sciences; namely, the idea that we are living in an “iron cage” distinguished by its materialist-individualist moral point of view.4 His argument that this Mainstream moral point of view is related historically to what he called a “protestant ethic” has prompted much research, including those who question the accuracy of that argument,5 those who compare the development of capitalism and business in protestant versus Catholic or other geographic regions,6 those who test different aspects of his arguments,7 and those who contend that what he characterizes as hallmarks of the protestant work ethic are not unique to protestants.8

An important aspect of Weber’s work that is occasionally referred to but seldom acted upon is his specific call for researchers and practitioners to facilitate escape from the iron cage. In particular, he provided two pieces of advice on how this might be accomplished. First, the materialist-individualist moral point of view that underpins the status quo must be overcome through the development of an alternative moral point of view that fosters a more balanced approach to life in general and to business in particular. Weber pointed to the merit of a moral point of view that emphasizes multiple forms of wellbeing (for example, physical, social, ecological, emotional, spiritual, intellectual, aesthetic) for multiple stakeholders (for example, individuals, neighbors, future generations). Second, although he himself was an agnostic, Weber argued that escaping the iron cage is most likely to occur if this moral point of view was grounded in religious beliefs.

In short, Weber argued that what people consider to be formally rational management theory and practice depends on their moral point of view.9 It only makes sense that a materialist-individualist moral point of view will lead to an approach to management that places primary emphasis on maximizing productivity, efficiency, profitability and competitiveness. He also noted how this Mainstream formal rationality would lead in turn to unintended consequences associated with the iron cage, where “technical and economic conditions … determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force” (emphasis added here).10 According to Weber, overcoming this “irresistible force” requires developing a new formal rationality based on a moral point of view, such as the Multistream approach, that places less emphasis on materialism and individualism.

In this paper, we hope to begin to address Weber ’s challenge by: a) building upon scholarship in Christian theological ethics and management studies to develop a Multistream moral point of view of management, and b) identifying specific Multistream managerial practices that will help to unchain the iron cage. In particular, we will examine what some core aspects of management theory and practice might look like if they were based upon a Multistream moral point of view. In the first part of the paper we review Weber ’s argument. In the second we will briefly describe and then compare and contrast how the four basic functions of management are performed differently from a Mainstream versus a Multistream approach. In the third, which constitutes the focus of our paper, we present a four-step process (consistent with biblical virtues and servant leadership practice) that managers can use to unchain the iron cage, and describe how this process is consistent with organizational learning theory. In the fourth, we will illustrate how this four-step process may be evident in Ephesians 4, a biblical passage that describes how to put Christian principles into practice in community. Finally, we highlight some key implications of our argument.

A History of the Iron Cage

Weber’s basic argument about how we have gotten ourselves into an iron cage can be depicted as in Figure 1. Although Weber may have been mistaken on some of the historical or theological details, the overall gist of his argument has been very well-received in the literature.11 We will briefly review the various aspects of Figure 1.12 First, Weber reviewed the growth of the Protestant movement and suggested that its distinguishing hallmarks are its emphasis on individualism (to be saved requires fulfilling an individual’s calling – salvation is no longer via community sacraments like confession) and on materialism (wealth is a symbol of God’s blessing and salvation).

Second, the preachers who promoted this particular moral point of view had an effect on how jobs were performed in the workplace. For example, businesspeople like Josiah Wedgwood, an important early innovator in the Industrial Revolution, provided support and encouragement for John Wesley when he began preaching in his region around 1760 and convinced listeners to live more disciplined lives than had been the custom.13 This included working disciplined hours and using financial resources to improve productivity, efficiency, competitiveness and profitability. As Weber quotes (and over-simplifies) Wesley: “religion must necessarily produce both industry and frugality, and these cannot help but produce riches.”14

Third, as intended, these Mainstream management practices resulted in unprecedented efficiency, productivity and profitability. Soon they were adopted by all managers who wanted to compete in the marketplace. Over time, the materialist-individualist moral point of view became thoroughly secularized and taken for granted, so that soon people accepted ideas like productivity and competitiveness and profitability as value-neutral, forgetting that they are based on a moral point of view that is relatively unique in the history of humankind.

However, as Weber noted over a century ago, there are unintended side effects to Mainstream moral point of view, and he was troubled that we may remain in its iron cage, captured “until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt.” His concern is evident in his lament: “Specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before reached.”15 Indeed, a growing body of contemporary research shows that an emphasis on a materialist-individualist moral point of view is associated with decreased overall wellbeing and happiness, lower satisfaction with life, poorer interpersonal relationships, and an increase in mental disorders, environmental degradation, and social injustice.16

Despite his awareness of the unintended consequences associated with the Mainstream approach, Weber recognized that it would be very difficult to unchain the iron cage. He knew that escape required developing new practices based on a moral point of view that places less emphasis on materialism and individualism. Moreover, he argued that the best chance for escape was if the approach had a religious or faith-based foundation, such as a Multistream approach. This is not to suggest that a humanist moral point of view could not give rise to Multistream practices, but rather that the religious component would provide an extra motivation to overcome the entrenched status quo. Whereas one might be able to develop a Multistream moral point of view based on any of a number of religions (e.g.,Buddhism or Islam), our goal in this paper is, perhaps ironically, to develop it within the Christian tradition that Weber argued had initially given rise to the Mainstream approach. Our goal is not as counter-intuitive as it may first seem, as there is some consensus among contemporary protestant scholars that there is a need to be unchained from the status quo. For example, a recent content analysis ofthe most frequently cited Bible passages in the first ten years of The Journal of Biblical Integration in Business suggests that a need for an approach akin to a Multistream moral point of view is well-recognized among Christian business scholars.17 Specifically, that study found that scholars differentiate between what they consider to be biblical versus conventional business and management theory and practice, with particular interest in developing the former.

The works of a number of scholars writing from diverse theological traditions point towards how Multistream management theory and practice could be grounded in the Christian faith. For example, Bruno Dyck and David Schroeder draw from Anabaptist theology to interpret Biblical texts and develop management practices that incorporate multiple forms of well-being.18 Helen Alford and Michael Naughton work from within Catholic natural law and teleology to argue for definitions of human flourishing beyond the material/economic.19 Jeff Van Duzer and his colleagues work from within the Creation, Fall, Redemption narrative structure of scripture to argue that the central purpose of business is service and stewardship.20 The important point to note is that despite all their different traditions, each works towards developing a “theology of management” that provides a moral point of view to support Multistream management.

Our goal in the rest of this paper is to build on the work of Weber and others to develop an understanding of how Multistream theory and practice can help managers loosen the bonds of the iron cage.

The Content of What Managers Do: The Four Functions of Management

Weber and others provide a compelling description of the Christian moralpoint of view that underpins Mainstream management. Others—like Dyck and Schroeder, Alford and Naughton, Van Duzer—describe a Christian moral point of view that underpins Multistream management. In this section we will briefly compare and contrast key differences in how Mainstream and Multistream managers perform their day-to-day jobs.

Perhaps the most influential conceptual framework to describe management work was developed by Henri Fayol (1916) almost a century ago.21 Today the idea that managers perform four basic functions—controlling, leading, planning, and organizing—pervades most of the introduction to management textbooks that are used by 40,000 students every year in the U.S. alone. In this section of the paper we will argue that each management function will be viewed and practiced differently from a Mainstream and a Multistream approach. As summarized in Table 1, our discussion will look at commonalities shared by the Mainstream and Multistream approaches for each of the four management functions, and then look at key differences between the two approaches. Our purpose in exploring similarities and differences between a Mainstream and a Multistream approach is to illustrate how the classic functions of management (the first column in Table 1) can be interpreted very differently and lead to a different management theory and practice depending on whether one has a Mainstream moral point of view (the second column in Table 1) or a Multistream moral point of view (third column in Table 1).22

Controlling refers to ensuring that the actions of organizational members are consistent with the organization’s values and standards. The Mainstream approach tends to focus on specific measurable standards, with standards enforced by vigilant specialists (e.g., quality control experts, supervisors, auditors). The Multistream approach, in contrast, is sensitive to a wider range of standards of well-being (e.g., paying attention to disadvantaged social groups, ecological sustainability, work-life balance, and so on) and to the views of a wider range of stakeholders (e.g.,owners, customers, suppliers, members, neighbors). Multistream managers do not see themselves as judging others, but more as being sensitive to the judgments of a variety of stakeholders.

Leading refers to ensuring that others’ work efforts serve to meet organizational goals. Here, Mainstream managers use their authority to cajole and reward and thus motivate others to work hard. Mainstream managers focus on developing instrumental interpersonal skills, which are used to get people to do productive things for them. In contrast, a Multistream approach—based upon humility, service to others, and peacemaking—is more consistent with “servant leadership,” in which a manager treats others with dignity and helps them to do their tasks. Multistream managers seek to nurture a workplace that facilitates building meaningful relationships. Multistream managers place greater emphasis on developing relational interpersonal skills, which are used to create and deepen connections between people, to share excitement and joy, and to participate in joint creative efforts.23 A Multistream approach to leading relaxes the pervasive Mainstream self-fulfilling economic assumption that everyone is self-interested; instead, a Multistream approach embraces and expects people to act altruistically—a self-fulfilling prophecy of a different sort.24

Planning means deciding upon an organization’s goals and strategies and the appropriate organizational resources required to achieve them. From a Mainstream approach, an important part of planning is management decision-making (though in specific circumstances, participative decision-making is recognized as a means to enhance productivity). Generally it is managers who analyze the data and make the decisions and develop the plans to maximize organizational efficiency, productivity, profitability and competitiveness. A Multistream approach places much greater emphasis on participative decision-making as the default mode and has a deliberate de-emphasis on managers making all the decisions. The Multistream approach emphasizes how managers work alongside others to set goals and design strategies. Multistream managers view persons as embedded in community and understand that the differences between these two are more apparent than real. Such managers recognize that individual and community well-being are closely related, and therefore they strive to ensure that decisions reflect the needs of multiple stakeholders (e.g., members, customers, owners, suppliers and neighbors).25

Finally, organizing means ensuring that tasks have been assigned and organizational relationships have been structured to facilitate meeting organizational goals. The Mainstream approach tends to have a primary concern for maximizing efficiency via specialization, centralization, formalization, and standardization. This approach seeks to find the one best way to organize, in light of contingencies, and get others to follow the rules. In contrast, a Multistream approach to organizing with a strong focus on community building, places greater emphasis on member sensitization, dignification, participation, and experimentation. A Multistream approach also goes beyond organizing merely to enhance efficiency or productivity: organizing involves inviting stakeholders to implement practices that will facilitate social justice, ecological sustainability, and address the needs of the most disadvantaged.

Even this brief overview of the Multistream approach to the four functions of management provides support for Weber ’s proposition that fleshing out management theory and practice from a Multistream moral point of view promises to offer a welcome alternative to the Mainstream iron cage. However, our goal in this paper is not to develop this Multistream approach more fully.26 Rather, in the rest of the paper we want to develop and describe a process managers can follow to un-chain the iron cage. In the next section we describe a four-phase process model that can help managers begin to unchain the iron cage in their everyday workplaces and facilitate transitioning from a Mainstream to a Multistream approach.

Unchaining the Iron Cage via a Multistream Four-Step Organizational Learning Process

Weber identifies four distinct biblical virtues that, interpreted from materialist-individualist moral point of view, can be seen to underpin Mainstream management theory and practice. In this section we will describe how those same four biblical virtues, when interpreted from a Multistream moral point of view, can form the basis for a four-phase process model that managers can use to unchain the iron cage (see Table 2).

As described in Dyck and Schroeder (2005), the four biblical virtues Weber identifies as having been used to underpin Mainstream management are brotherly love, submission, obedience, and non-worldliness (first column in Table 2). Weber describes how, interpreted via a (Christian) Mainstream moral point of view: a) brotherly love gives rise to specialization (e.g., people can demonstrate their love

for others by accepting and fulfilling their specific roles and tasks in the larger group); b) submission gives rise to centralization; c) obedience gives rise to formalization; and d) non-worldliness gives rise to standardization (second column in Table 2). However, Dyck and Schroeder go on to describe how these same four biblical virtues can be interpreted differently from a (Christian) Multistream moral point of view and give rise to four parallel Multistream management practices: a) brotherly love gives rise to sensitization; b) submission gives rise to dignification; c) obedience gives rise to participation; and d) non-worldliness gives rise to experimentation.27

Of course, our point here is not to argue that one interpretation is more Christian than the other. Indeed, Dyck and Weber28 provide an empirical look at self-professing Christian managers and found that, as expected, managers who are relatively high on materialism-individualism scored higher on the Mainstream items (column 2) and lower on the Multistream items (column 3) compared to managers who are relatively low on materialism-individualism.

Dyck and Schroeder speculate that the four Multistream management practices (column 2) may be linked one to another in a way that points to a process to unchain the iron cage. Pointing to the overlap between Greenleaf’s four-step servant leadership process model29 and these four Multistream practices, Dyck and Schroeder suggest that implementing these four practices sequentially may hold a key to unchaining the iron cage. They go on to suggest that Multistream managers can implement each practice in any organizational setting, including when working within organizations dominated by a Mainstream approach.30

First, contemporary managers can become sensitive to injustices built into existing organizational structures and systems. Robert Greenleaf, when he was a Vice President at AT&T, became sensitized to the fact that women were under-represented at AT&T and African Americans were under-represented in managerial positions. Second, contemporary managers can approach others and treat them with dignity, expecting them to also be interested in correcting injustices once they have been made aware of them. This is how Greenleaf approached other managers at AT&T, deliberately taking time to talk about and remember shared successes (rather than invoking his managerial decision-making authority). Third, contemporary managers can invite other stakeholders to participatively identify and develop possible solutions (rather than developing and imposing solutions from top-down). Greenleaf asked his co-workers to develop ideas about how to hire more women and how to promote more African Americans. Finally, contemporary managers can help stakeholder to implement their solutions, recognizing that there is no perfect structure and thus there is a need for ongoing learning and improvement (experimentation). This is akin to Greenleaf providing support for those managers who wanted to implement solutions, celebrating improvements, and welcoming other members to implement voluntarily similar solutions.

The Four Steps of Unchaining as an Example of Organizational Learning

Building on and extending the four-step process model alluded to by Dyck and Schroeder, we argue that it is consistent with a specifically Multistream interpretation of the organizational learning process (see column 4 in Table 2). Linking their speculated model to the organizational learning literature (and in the next section of the paper to the teachings found in Ephesians chapter 4) promises to provide: a) a stronger conceptual and theoretical basis for future research in this area; and b) a greater understanding and confidence for practitioners to use the four steps to loosen the iron cage in the workplace.

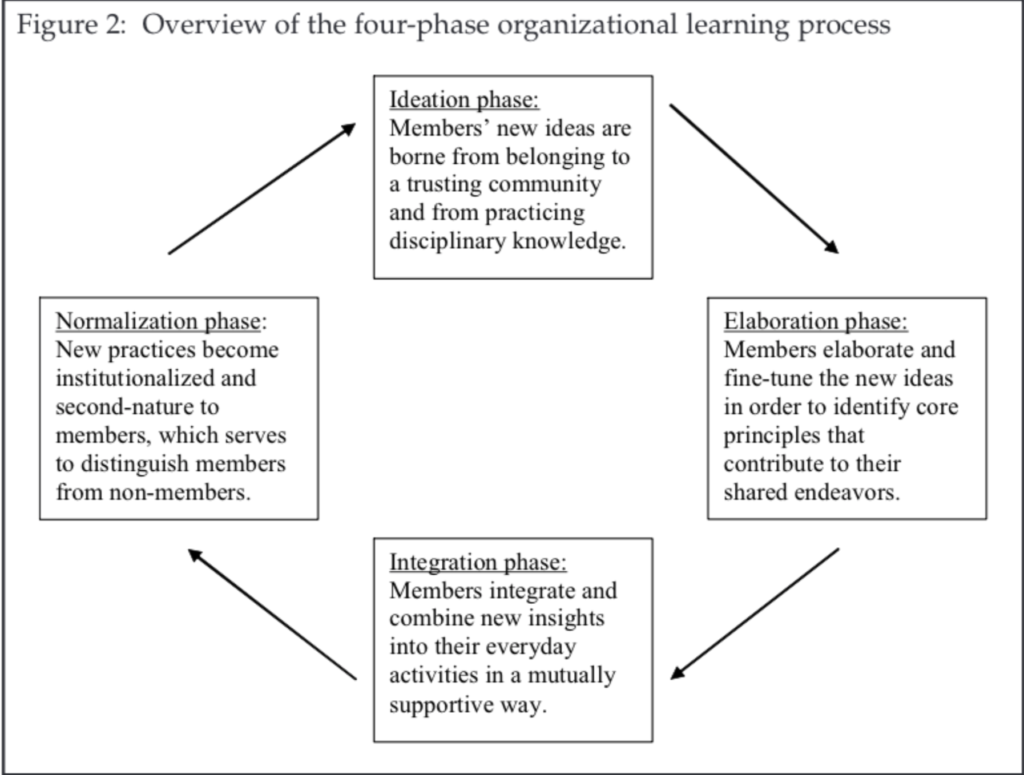

The past two decades have witnessed increasing theoretical and empirical work in the area of how organizations learn. Organizational learning is seen as a key to explaining why some organizations are more adaptable and flourish while other organizations make poor decisions and stagnate. Put differently, often organizational learning is argued to be a key to long-term organizational viability and competitiveness. There is growing consensus that organizational learning can be seen to unfold in four general phases.31 These four phases are evident in two of the foremost models in the organizational learning literature.32 While certainly there are differences between these two models, we draw from both models to develop the organizational learning model as presented in Figure 2. The model can be seen as a general model of social (versus individual) learning, and the four stages have been observed at various levels of analysis, including organizations, groups, and even the community level of analysis.

Phase 1: Ideation

The sources of the ideas that trigger organizational learning may appear to be mysterious, but there is increasing understanding on the conditions that facilitate these ideas. New ideas are rooted in past experience, and in particular in experience shared within a group or community and among the actual members of an organizational unit where organizational learning is occurring.33 Ideation is facilitated when members trust one another and share many past experiences. Intimate and deep mutual understanding facilitates empathy and allows the tacit knowledge of each member to be shared with others. Often this tacit knowledge is embedded in experience, practices, and emotions, and is communicated in nonverbal ways. This tacit-to-tacit knowledge transfer, where the tacit knowledge of multiple members combines in ways that no one member could imagine, serves as the foundation of developing new ideas. Put differently, organizational learning is not grounded in rational analysis of explicit knowledge, but rather it is characterized by the burst of insight — the “aha” moment — that comes from a place deep within a community. Mary Crossan and her colleagues call this intuition the “recognition of the pattern and/or possibilities inherent in a personal stream of experience.”34 Intuition can also be seen to be borne out of past experience and relationships in away that defies linear rational analysis. It is rooted in members who have a deep knowledge and experience with the disciplinary practices of a particular community or organization.35

In terms of the four Multistream practices, we suggest that ideation is more likely to occur when organizational stakeholders are deliberately sensitive to each other’s needs and to the shortcomings of the status quo. Such sensitivity comes from intimate knowledge of and mutual experience with existing operations. While such ideas can be identified by external stakeholders or specialists, often the most relevant ideas come from stakeholders who have a deep understanding of the status quo.

Phase 2: Elaboration

It is one thing for organizational members to have “aha” moments. Half-thoughts, fleeting ideas, momentary connections, and ephemeral insights are not unusual in organizational life.36 It is quite another thing to translate the new idea into principles that are both understood and accepted by other organizational members. This happens in the second phase of the organizational learning process—elaboration. Ikujiro Nonaka calls this phase “externalization,” which draws attention to both a) how the new insights need to be shared and discussed with other people in the group, and b) how the initially often half-baked “aha” idea gets fine-tuned and fleshed out as it makes the transition from what he calls “tacit” to become “explicit” knowledge.37 Dialogue and the sharing of perspectives, often using metaphors, allows members to externalize knowledge that was previously invisible. Crossan et al call this phase “interpreting:” “the explaining, through words and/or actions, of an insight or idea to one’s self and to others.”38 Interpreting involves members in conversation and dialogue. Interpreting allows principles to be articulated, named, and to become part of the cognitive maps of various stake-holders.

In terms of the Multistream practices, dignification is a key component of elaboration. Treating other stakeholders with dignity creates a space where they feel welcome to contribute elaboration. Being considerate of others models the kind of behavior required to facilitate learning, and it prompts stakeholders to consider the implications of new ideas from their own and others’ perspectives. And, because dignification welcomes and values stakeholders from a wide cross-section of the organization, it enhances the interpretation and fine-tuning of the new idea.

Phase 3: Integration

The focus in this phase is on how to incorporate (a) the principles developed during the elaboration phase into (b) the existing everyday practices of the organization. Combining new principles with existing practices is facilitated by documenting the new rules and policies and procedures, thereby establishing a body of explicit knowledge that can be shared relatively easily among organizational members.39 The focus in this phase is on accomplishing coherent collective action and on “taking coordinated action through mutual adjustment.”40 Learning is impeded by those who refuse to follow the new rules and fail to exhibit a spirit of mutual adjustment.

In terms of the Multistream practices, participation is a key component of integration. This is quite different than a centralized manager formalizing a new idea and then imposing it on others. Indeed, research suggests that members who participate in planning and deciding on the ideas and rules that guide their work are more likely to perform at a higher level than those who do not participate and are given the exact same rules. For example, members respond differently to a rule on how distribute earnings when they have participated in developing it than if the very same rule is imposed by managers.41

Phase 4: Normalization

In this phase, members “learn by doing” and thereby master the new way of doing things, which eventually become second nature to them. Repetition and “learning by doing” result in the innovation becoming embedded in members’ personal routines via their organization’s “systems, structures, procedures, and strategy.”42 The learning cycle is completed as the new way of doing things becomes part of the tacit knowledge and skill set of members, which Nonaka calls “internalization.” In describing this phase as institutionalizing, where the knowledge is embedded in organizational institutions, Crossan draws attention to two items. First, this points to a difference between organizational learning versus individual learning (the institutions are embedded in the organizational structures and systems and will persist even when new members join the organization). Second, this also helps to distinguish and point to possible tensions between members and non-members. People can choose among various competing institutional norms, and the norms that they follow indicate which institutions and organizations they belong to.43

In terms of the Multistream practices, experimentation is an important component of implementation. Experimentation describes the Multistream attitude to implementation. From a Multistream perspective, the goal is not so much to develop a uniform standard that represents the “one best way” for everyone to follow. Rather, the idea of experimentation makes implementation easier and less permanent (because if a newly-implemented idea does not seem to be working, then lessons can be learned and changes can be made). This should foster more learning in the future.

Cyclical Nature of Model

It is worth noting that the implementation phase is followed by a new ideation phase of the organizational learning process. The norms of the community from earlier learning cycles become the experiences and tacit knowledge that inform subsequent ideation phase. In this way, the learning process can be seen as a continuous cycle of change; organizations are constantly moving through the four phases, sometimes in various phases at the same time at different levels of analysis. Organizational knowledge flows can be seen as “feed forward” (from individual members to groups and institutional norms) and as feedback (from institutional and group norms to the individual members).

There are numerous implications that come from pointing out how unchaining the iron cage can be seen through the lens of the four-step organizational learning process. We will highlight only two. First, it draws attention to the importance of manifesting all four Multistream practices listed in Table 2. It is not sufficient to only be sensitive to problems associated with the status quo—if you fail to act on those insights, you will remain ever-mired in the iron cage. Similarly, it is insufficient to experiment only with new ways of operating—the key is to ensure that the experiments are born from a community where members are treated with dignity. Again, it is not sufficient to allow people to participate if one does not treat them with dignity and does not allow them to opt in or out of experiments to improve the status quo. And so on. Failing to exhibit these four Multistream practices insequence may contribute to further frustration, as members see the promise of escaping the iron cage but fail to experience any sustained liberation.

Second, understanding unchaining from the iron cage as organizational learning points to the processual nature of Multistream management. From a Multistream perspective, the emphasis is not so much on finding the one best way to organize. All organizational structures and systems will have shortcomings. No organization is perfect. Instead, the emphasis is on the process of improvement. Liberation from oppressive structures is not a destination but rather a journey. It is by practicing the four-step process in the everydayness of their lives that Multistream managers in effect demonstrate their freedom from the iron cage, and how they invite others to do the same.

A Biblical Example of the Four-Phase Unchaining Process

In this section we will describe how aspects of the four-phase unchaining model may be evident in Ephesians chapter 4, a particularly relevant passage for our paper. The first three chapters of Ephesians emphasize theological teachings of the church (i.e., developing its moral point of view), and chapter 4 marks the transition to teachings about how to put that theology into practice (i.e., implications for how to manage). Chapter 4 represents a shift “from the doctrinal to the practical.”44 In contemporary terms, Ephesians 4 might be seen as a manual for how to “be the church” or how to become an evermore godly congregation. In this chapter Paul “turns to the practical outworking of this ideal [described in first three chapters] in everyday living.”45 In terms of this special journal issue, Ephesians 4 might be seen as a description of how organizations can become unchained (loosed) from the iron cage.

What we found striking in reading this passage, and what is highlighted in Table 3, is how Paul’s overall counsel in chapter 4 seems to follow the four-phase unchaining model. Although we are not suggesting that the biblical writers were aware of the four practices of Multistream management as we have described them, nor of how they correspond to the four-phase learning model as we have described, we offer our interpretation of this passage as an argument that our ideas are not inconsistent with the teachings in the biblical text. Of course, we are not arguing that ours is the only or the best interpretation of this chapter. Indeed, we have noted previously that both a Mainstream and a Multistream interpretation of the Bible is possible, and similarly, we do not purport to suggest that our interpretation of Ephesians 4 in any way provides conclusive evidence or proof of the four-phase unchaining process model we described here. Even so, it does provide an intriguing, and possibly inspiring, example of our basic argument.

Note how, consistent with the first phase of organizational learning model—ideation—Paul begins his counsel (Eph. 4: 1-6) by emphasizing the importance of members belonging to a trusting community (“there is one body and one Spirit,” v.4) and encouraging them to make every “effort to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (v. 3). And consistent with the Multistream practice associated with this phase of the learning model, Paul points to the need to be sensitive to others when he exhorts readers to “bear with one another in love,” and to practice humility, gentleness and patience. We believe that when people are humble in Christian community then they will sensitive to each others’ needs and to God’s voice.

Then, consistent with this second phase of organizational learning model—elaboration—Paul continues his counsel (Eph. 4: 7-13) by emphasizing the importance of taking the various insights and gifts that members have and, in community, developing them to maturity. He describes how members are equipped with a variety of gifts, which they should share and develop in community in order to build up the church (v. 12). Consistent with Multistream practices, Paul lets readers know that they are to treat each other with dignity and respect because each member has received their gifts and grace from God (vs. 7-8).

Paul continues his counsel (Eph. 4: 14-16) by emphasizing ideas consistent with the third phase of the organizational learning model—integration—by noting the importance of integrating every insight and gift and member into one body. Individuals should not be separate, but rather get their meaning and fullness when integrated one with the other. Members should ensure that “the whole body, joined and knit together by every ligament with which it is equipped, as each part is working properly, promotes the body’s growth in building itself up in love” (v. 16). Consistent with the Multistream practice associated with this phase, Paul lets readers know that the key to the ongoing growth and integration of the pieces into a building body is to have members participate as a “we” and help the body to grow by “speaking the truth in love” (v. 15). This ongoing participation in integration is contrasted deliberately with being tricked into following false doctrine (e.g., a secular moral point of view) (v. 14).

Finally, consistent with the fourth phase of organizational learning model—normalization—Paul ends his counsel (Eph. 4: 16-32) by emphasizing that when community members have “learned Christ” (v. 20: emphasis added here), they will put off their old habits and adopt new practices. As if to underline that these new practices are the result of having learned together in community, Paul’s draws attention to the how members are “renewed in the spirit of your [their] minds” (v.23; emphasis added here). And consistent with the Multistream practice associated with this phase, after Paul identifies a list of what members should do (e.g., speak truth, give up stealing, speak no evil, put away bitterness – vs 25-31), he ends on a note that points to entering the first phase of the learning process anew as members constantly experiment in community. Members are called to forgive one another when they make mistakes, such as may occur when their experiments with righteous living go awry. Knowing that every person, no matter how well-intentioned, will make mistakes draws attention to the need for members to be kind to one another and forgive each other as they grow in love and knowledge in the learning process.

Discussion

Of course, any article or journal that seeks to “unchain the iron cage” can only begin to scratch the surface of what that means. Our aim in this article is to contribute to the literature that looks at what can be done at a managerial level of analysis to escape the iron cage. Our primary goal is not to provide conclusive answers to this important challenge, but rather to build on past research and help to set the agenda for future research. The following are some highlights of our argument.

First, we hope that recalling Weber’s basic argument depicted in Figure 1 both encourages and inspires readers. We expect readers may find it encouraging to see how a group of sincere and devout Christians who put into practice their understanding of the Protestant ethic served to change the way that many others do business. In addition, we expect that some readers may be inspired by Weber’s challenge to embrace a less materialist-individualist moral point of view and develop new business practices that address some of the unintended consequences associated with the status quo. Indeed, that is precisely the goal of this special issue.

Second, we hope that our discussion surrounding Table 1 draws attention to the importance of how we “name” what management is all about. Just as God called Adam and Eve to name their world, so also we constantly name and rename what is important in our world. In this paper we discuss definitions that are used and could be used to help name a new approach to management. In particular, we hope that our discussion inspires readers who are interested in unchaining Weber’s iron cage to join us in developing Multistream names and techniques further for the four management functions. At the very least, Table 1 reminds us that as scholars and instructors we have a moral obligation to point out that Mainstream theoryis not value-neutral. Simply perpetuating the status quo, without offering an alternative or recognizing its underlying ethic, is akin to imposing materialist-individualist values on others. Indeed, research suggests that business students become more materialist-individualist as they proceed through their programs of study.46 We would argue that it amounts to moral negligence to teach or impose Mainstream management principles without pointing out explicitly and deliberately that they are not value-neutral, even for those who themselves adhere to a materialist-individualist ethic. The same would be true of teaching only Multistream theory. We encourage management educators, regardless of their personal moral point of view, to teach management from at least two moral-points-of-view (e.g.,both Mainstream and Multistream) in order to point out the underlying values of approaches to management and in order to provide students with a conceptual framework for working out their own approach to management based on their own moral point of view.

Third, we hope that our discussion surrounding Table 2 helps readers to understand a relatively simple, elegant and challenging process by which managers can unchain the iron cage. If managers emphasize the four Mainstream practices, then they will reinforce the status quo that enhances Weber’s iron cage. In contrast, if managers emphasize the four Multistream practices, then they will enhance organizational learning that unchains the iron cage. Managers who over- (or under-) emphasize one of the four phases of the model may, as a result, stifle organizational learning and thereby minimize unchaining. In particular, managers should pay attention to the learning process and draw on other people to help shore up practices where managers themselves are weak.

Finally, we hope that our analysis of Ephesians 4 helps readers see how the four-step unchaining model is not inconsistent with the biblical text and indeed may help readers who are interested in applying the lessons from the model in the various religious and other communities to which they belong. Moreover, our exploratory study may encourage Biblical scholars to examine the merits of our interpretation of Ephesians chapter 4 and to explore whether there are similar process models embedded in the other biblical texts.47

In conclusion, both the Mainstream and the Multistream approaches are value-laden—neither approach is value-neutral. Moreover, both can and have been shown to be grounded in an interpretation of Christian values and the biblical text. Thus, we must be careful not to judge one as “true” and the other as “false.” However, consistent with the theme of this special issue and with Weber’s proposition, we can argue that the Multistream approach is better-suited to liberate people from the iron cage. In particular, we argued that following four important Multistream practices in sequence may foster organizational learning that helps people become unchained from the iron cage. We invite readers to join us in fleshing out and elaborating Multistream management theory and practice. It is challenging work, but we believe that the potential benefits are worth the effort.

Cite this article

Footnotes

- A more developed discussion of these two Weberian types, which the authors call Conven-tional and Radical management, can be found in Bruno Dyck and David Schroeder, “Man-agement, Theology and Moral Points of View: Towards an Alternative to the ConventionalMaterialist-Individualist Ideal-Type of Management,” Journal of Management Studies 42 (2005):705-735.

- Royston Greenwood and Thomas B. Lawrence, “The Iron Cage in the Information Age: TheLegacy and Relevance of Max Weber for Organization Studies,” Organization Studies 26 (2005):493-499.

- Stewart Clegg, “The Moral Philosophy of Management,” Academy of Management Review 21(1996): 3, 867-871.

- Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Transl. T. Parsons (New York:Scribner ’s, 1958). For a more comprehensive development of this argument, see Bruno Dyckand David Schroeder, “Management, Theology and Moral Points of View.”

Ethan Crowell, Weber’s Protestant Ethic and His Critics, Master of Arts Thesis, University ofTexas at Arlington (2006).- See literature review in Jacques Delacroix and Francois Nielsen, “The Beloved Myth: Prot-estantism and the Rise of Industrial Capitalism in Nineteenth Century Europe,” Social Forces80 (2001): 509-553.

- See Harold B. Jones Jr., “The Protestant Ethic: Weber’s Model and the Empirical Literature,”Human Relations 50 (1997): 757-778.

- Amy Sherman, The Soul of Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); MichaelNovak, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism (New York: Touchstone, 1982).

- Note that, instead of “moral point of view,” the term Weber would have used is “substan-tive rationality.” However, in response to a reviewer’s suggestion to enhance the reader-friendliness of the paper, we have chosen throughout the paper to use the term “moral pointof view” instead of using a variety of similar terms that have been in the various literatureswe draw from and wish to contribute to (e.g., substantive rationality, value-based rationality,ethic, worldview).

- Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 181.

Robert T. Golembiewski, Men, Management, and Morality: Toward a New Organizational Ethic(New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1989); Stewart W. Herman, Durable Goods: A Cov-enantal Ethic for Management and Employees (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press,1997); Guy F. Hershberger, The Way of the Cross in Human Relations (Scottdale, PA: HeraldPress, 1958); Robert Jackall, Moral Mazes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); LauraNash, Believers in Business (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1994); Michael Naughtonand Thomas Bausch, “The Integrity of a Catholic Management Education,” California Man-agement Review 38:4 (1996): 119-140; Michael Novak, Business as a Calling (New York: FreePress, 1996); Stephen Pattison, The Faith of the Managers: When Management Becomes Religion(London: Cassell, 1997); Jeffrey Pfeffer, Organizations and Organization Theory (Marshfield,MA: Pitman Publishing Inc., 1982); Calvin Redekop, Stephen C. Ainlay, and RobertSiemens, Mennonite Entrepreneurs (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1995).- For a fuller discussion of many of these points, see Dyck and Schroeder, “Management,Theology and Moral Points of View.”

- John Langton, “The Ecological Theory of Bureaucracy: The Case of Josiah Wedgwood andthe British Pottery Industry,” Administrative Science Quarterly 29:3 (1984): 330-354.

- Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 175

- Ibid., 181 -182.

- For summaries, see Robert Giacalone, “A Transcendent Business Education for the 21st Cen-tury,” Academy of Management Learning and Education 3 (2004): 415-442; Tim Kasser, The HighPrice of Materialism (Cambridge, MA: A Bradford Book, MIT Press, 2003); James E. Burroughsand Aric Rindfleisch, “Materialism and Well-Being: A Conflicting Values Perspective,” Jour-nal of Consumer Research 29 (2002): 348-370; Marsha L. Richins and Scott Dawson, “A Con-sumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development andValidation,” Journal of Consumer Research 19 (1992): 303-316; John A. McCarty and L. J. Shrum,“The Influence of Individualism, Collectivism, and Locus of Control on Environmental Be-liefs and Behavior,” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 20:1 (2001): 93-104; Patricia Cohenand Jason Cohen, Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996);William E. Rees, “Globalization and Sustainability: Conflict or Convergence?” Bulletin of Sci-ence, Technology and Society 22:4 (2002): 249-268.

- Bruno Dyck and Fred Starke, “Looking Back and Looking Ahead: A Review of the MostFrequently cited Biblical Texts in the First Decade of The JBIB,” Journal of Biblical Integration inBusiness (2005): 134-153.

- Management, Theology and Moral Points of View: Towards an Alternative to the Con-ventional Materialist-Individualist Ideal-Type of Management.”

- Helen Alford and Michael Naughton, Managing as if Faith Mattered (Notre Dame: NotreDame University Press, 2001).

- Jeff Van Duzer, Randal Franz et al., “It’s None of your Business: A Christian Reflection onStewardship,” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 3:4 (2006): 348-374.

- Henri Fayol, Industrial and General Administration (Paris: Dunod, 1916).

- For a much more fully developed discussion of these similarities and differences, see BrunoDyck and Mitchell Neubert, Management: Current Practices, Future Directions (Boston, MA:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, in-press, 2010).

- Steven E. Gutstein and Rachelle K. Sheely “Friendships are Relationships,” in RelationshipDevelopment Intervention with Young Children (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2002), 17-22.

- Fabrizio Ferraro, Jeffrey Pfeffer, and Robert I. Sutton, “Economics Language and Assump-tions: How Theories Can Become Self-Fulfilling,” Academy of Management Review 30 (2005):8-24.

- Steven M. Mintz, “Aristotelian Virtue and Business Ethics Education,” Journal of BusinessEthics 15 (1996): 827-838.

- See Dyck and Neubert, “Management: Current Practices, Future Directions.”

- “Management, Theology and Moral Points of View: Towards an Alternative to the Con-ventional Materialist-Individualist Ideal-Type of Management.”

- Bruno Dyck and J. Mark Weber, “Conventional and Radical Moral Agents: An Exploratorylook at Weber’s Moral-Points-of-View and Virtues,” Organization Studies 27:3 (2006): 429-450.

- Described in Richard P. Nielsen, “Quaker Foundations for Greenleaf’s Servant-Leadership and ‘Friendly Disentangling Method,’” In Larry C. Spears, ed., Insights on leadership (NY:John Wiley & Sons, 1998), 126-144.

- Dyck and Schroeder, “Management, Theology and Moral Points of View.”

- Thomas Lawrence, Michael K. Mauws, Bruno Dyck and Robert F. Kleysen, “The Politics ofOrganizational Learning: Integrating Power into the 4I Framework,” Academy of Manage-ment Review 30:1 (2005): 180-191.

- Mary M. Crossan, Henry W. Lane, and Roderick E. White, “An Organizational LearningFramework: From Intuition to Institution,” Academy of Management Review, 24:3 (1999): 522-537; Ikujiro Nonaka, “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation,” Organiza-tion Science 5:1 (1994): 14-37.

Ikujiro Nonaka, Ryoki Toyama and Noboru Konno, “SECI, Ba and Leadership: A DynamicModel of Knowledge Creation,” Long Range Planning 33 (2000): 5-34.- Crossan et al., “An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution.”

Lawrence et al, “The Politics of Organizational Learning: Integrating Power into the 4IFramework.”- “The Politics of Organizational Learning: Integrating Power into the 4I Framework.”

- Nonaka, “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation.”

- “An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution,” 525.

- “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation.”

- “An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution,” 525.

- Christine Cooper, Bruno Dyck, and Norm Frohlich, “Improving the Effectiveness ofGainsharing: The Role of Fairness and Participation,” Administrative Science Quarterly 37 (1992):471-490.

- “An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution,” 525.

- “An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution.”

- A. Skevington Wood, “Ephesians” in Frank E. Gaebelein, ed., The Expositor’s Bible Commen-tary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1978), 54.

- Ralph P. Martin, “Ephesians,” in Donald Guthrie, Alec Motyer, Alan.M. Stibbs, Donald F.Wiseman, eds., The New Bible Commentary: Revised Edition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publish-ing, 1970), 1115.

- For example, research cited in Ferraro et al, “Economics Language and Assumptions: HowTheories can Become Self-Fulfilling.

- ”For an example of how the four-phase model is evident in the Gospel of Luke, see BrunoDyck and Laurence Broadhurst, “A New Approach and Methodology to Study Chiasms: AnExploratory Look at Luke’s Journey Narrative,” in Canadian Society of Biblical Studies Con-gress (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, 2007).