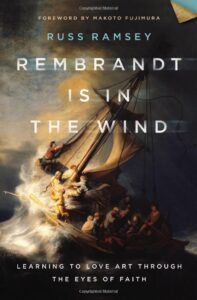

Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art through the Eyes of Faith. Foreword by Makoto Fujimura

Though few of us have the patience to really contemplate them, great pictures are rich “icons” of human nature. They are considered great precisely because they contain timeless, complex, interlocking truths in one small “box.” They are the world’s most dazzlingly efficient form of deep, rich, and instantaneous-yet-endless communication.

The old platitude says “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Well, the great works of art have generated hundreds of thousands—even millions—of words, and they will generate more. As an essentially ekphrastic writer on images myself, I add copiously to the pile.

And why do images have this distinction? For me, it comes down to their ability to combine three things: full-immersion sensory embodiment, in the form of evoked spaces and settings; rich narrative and symbolism that taps into high truths and deep archetypes; and expressive action and movement that reveals the artist’s state of mind. (The last occurs in the form of maker’s marks—brush-strokes and the like. Imagine the long, juicy, curving strokes in van Gogh’s Starry Night.) All these things are combined in a rectangle that can be “read” instantaneously—in a flash. But then, like rain on dry soil, these aesthetic “drops” take a moment, or a lifetime, to “sink in” and trickle down, suffusing and excavating, creating channels and reservoirs, watering roots and quickening seeds.

Take Rembrandt van Rijn’s biblical scene Christ on the Sea of Galilee, for example—the cover image for Russ Ramsey’s new book. Here Rembrandt, the consummate Baroque master, draws us into a stormy night on a turbulent sea: we feel the salty air, the whipping wind, and the rocking, creaking deck beneath our feet. Then, as we look closer, we see the dumbfoundingly calm profile of Jesus as he speaks to his frantic disciples. What first appeared as an ordinary Dutch seascape (albeit a dramatic one) now takes on spiritual meaning. We find ourselves in the anxious faces and desperate gestures of the disciples, and we wonder at Christ’s serenity. Perhaps we see ourselves most in the face of the disciple in blue, who looks outward with taut vigilance. (If we know our art history, we know this disciple is Rembrandt himself!) Amidst all this, we feel the atmosphere Rembrandt has created with his soft shapes, organic lines, and expressive brushstrokes that range from short-and-choppy to thick-and-sweeping. This is a deeply felt painting whose forms were created with the personal, spontaneous distinctiveness of a signature. Though a readable picture, it is also the complex “autograph” of a uniquely sensitive and probing mind.

Russ Ramsey, a Presbyterian pastor and erstwhile artist, is intuitively aware of the richness of great artworks, and his new book demonstrates this in spades. Ramsey is also a natural writer who no doubt enjoys the sometimes surprising exercise of letting one’s yearnings and wonderings unfurl through words. In this book, a pleasant and meditative ekphrastic exercise, Russell finds timeless spiritual meaning in a series of (more or less) canonical Euro-American artworks.

Ramsey’s project, here, is at once highly traditional and somewhat unusual. It is unusual because we do not generally expect American, Protestant pastors to wax poetic, in thousands of words, about relics of high culture. And it is even more unusual for evincing an artsy sophistication one wouldn’t associate with a mass-market religious book. But Rembrandt is in the Wind feels traditional because it shares (whether knowingly or not) in a long tradition of ekphrastic writing about the “old masters” that has shaped English-speaking tastes and consciences for a few hundred years.

The idea of the “old master”—of the canonical “great artist” hailing from days of yore—seems to have emerged around the year 1700, just as the Enlightenment was taking hold in Europe. At this time, a two-pronged development was unfolding: scholars were enthusiastically ranking and taxonomizing everything, and rational minds were laboring to put all that old, florid, mystical stuff (from the superstitious past) into tidy, unthreatening boxes. This resulted in the beginnings of what the French intellectual Andre Malraux has called “the Museum Without Walls”—a set of venerable names and images that have been tested, tamed and grouped together into a sort of dignified, floating patrimony Put into this benign “old master” context, the inhabitants of the “museum without walls” became rewarding ground for endless analysis and appreciation by the “enlightened” modern mind. Provided they stayed within their bounds, of course.

Malraux’s “Museum Without Walls” really depended on the invention of photography to take off and gain sway over the popular imagination. And indeed, once the high-quality photographic reproduction of artworks became possible in the late 1800s, the genre of the “old master book” exploded in popularity. One needs only browse a high-end used bookstore to find many gorgeous specimens of this once-popular form. Between gold-lettered, heavy covers, art historians, artists, and other cultural elites poetically and perceptively unpacked all kinds of “old master” paintings for eager audiences—particularly American audiences. For in the settler communities of young America, deprived of the ancient European infrastructure that surrounds one with antique beauties even as one walks down the street, there was a deep hunger for heritage, culture, and context—especially after the destabilizations of the American Civil War.

Ramsey’s book, comprised of an introduction plus nine chapters devoted to single, more-or-less canonical artists, sits squarely in this tradition. Many of Ramsey’s chosen artists are popular characters from 19th-century “old master” books (e.g., Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and Vermeer), while others have achieved indisputable “new master” status (e.g. Vincent van Gogh and Edward Hopper). A few others are not yet household names but are still well known to art lovers, including the prodigious African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (well on his way to becoming a “new master”), the proto-Impressionist Frederic Bazille, who made some highly influential paintings before his untimely death at age 28, and the fascinating artist-turned-missionary Lilias Trotter, the only woman featured in the book.

In each chapter, Ramsey elegantly weaves the artists’ defining life struggles into an empathetic discussion of their works toward the end of illuminating challenges common to the human condition. The works of Ramsey’s chosen artists are shown to be not merely technical experiments or celebrated commissions, but extensions of their makers’ souls (and sometimes all three). Caravaggio, for example, made indelible paintings that both fulfilled specific criteria for patrons (like the wealthy Cornaro family in Rome) and worked through deep issues personal to the artist (for example, moral shame coupled with spiritual yearning). This tightrope walk is one of the marks of timeless artwork, uniting public and private, specific and general, historical rootedness and “modern” relatability.

The chapters on Caravaggio, Van Gogh, and Hopper are perhaps the most seamlessly successful in Ramsey’s book, as these artists’ personal struggles shine so clearly through in their work, making connections feel natural and inevitable. Other chapters can feel a bit more labored—their core ideas divulging themselves a bit less organically. Ramsey’s chapter on Rembrandt is one of the most multi-pronged and challenging in the book, as it treats not only Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee, but also the eccentric collector who enshrined it in a Boston art museum (Isabella Stewart Gardner), together with the fallout from its spectacular theft in 1990. Ramsey finds a way to weave these themes together, and the chapter is certainly informative, but the result is not as sharp and memorable as the author’s discussion of (for example) that singular poet of loneliness, Edward Hopper.

Across all the book’s essays, with their varying levels of unity and ambition, Ramsey distinguishes himself as a true art connoisseur. He is absolutely not an opportunist who has learned his subject quickly solely for the purpose of writing a mass-market book about it. No—Russ Ramsay clearly knows and loves visual art. Visual art creates imaginative environments, and Ramsey knows how to enter those environments. Visual art sends nuanced symbolic messages, both explicitly and implicitly, and Ramsey knows how to read them. Visual art is a product of gesture and feeling and embodied engagement with a material. Ramsey gets that, feels that. As a guide, he is trustworthy, and his instincts are well-honed and good.

Consequently, Ramsey’s book is a good starting point for modern Christians interested in exploring their visual heritage. This is a visual heritage that was for hundreds of years explicitly, unquestionably Christian, and that has been even afterward (even in our modern age of doubt) suffused with the afterglow of Christian values without which they could not have existed.

It is high time, in fact, that modern and post-modern Christians, who have tended to live in the seeker-sensitive “now,” become more educated about the cultural riches of their inheritance. The vast majority of us live amidst a wealth of cultural stimuli that far surpasses even the great libraries and private galleries of old European kings. The average American teenager may see more images in a month than a great, sophisticated collector like Isabella Stewart Gardner saw in a lifetime! American church culture can no longer subsist on the thin gruel of stock-art landscapes on PowerPoint clipart. It no longer satisfies. Ramsey helps address this lack.

Furthermore, in this age of uncertainty, fluidity, and perhaps erosion, when it seems, as the poet Yeats once said, “the center cannot hold,” it is time for us Christians downstream of the evangelical and mainline Protestant traditions (both culturally shallow) to discover, more broadly and distantly, where we came from. This is not so that we might exclude what is “other,” but so we can understand ourselves more deeply, grasping our inherited identities in a culturally diverse world. Fluid, flashing modernity gives an impression of constant change, always packaged as “improvement,” that caters to the egos of consumers desperate to believe they are the most enlightened people who have ever lived. But in fact, in very significant ways, there is (as King Solomon said), “nothing new under the sun.”

Books like Rembrandt is in the Wind help, in a gentle way, to counter a bias, verging on bigotry, endemic to the modern condition. It is a bias against the past and the people who lived there—people neither better nor worse than us. I believe that as we learn more about our own heritage—our deep roots and the streams that have watered them—we will discover a flow that has watered every great culture in the history of the world. That is, we will discover anew the features of a common humanity deeply understood not only by the world’s great artists, but by the world’s great missionaries, saints and evangelists, who saw Christ in everyone.

The God who became human, by ageless plan, “slain from the foundation of the world,” has left His mark on every human thing. And when He returns, He will gather it all, past and present, near and far, into heaven. His will be a land of everything good, and nothing left behind—of shining echoes, stacked harmonies, deep convergences, and prismatic lights. As we gather in our past, we gather in the Kingdom.

Thank forr finlly writing about >Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Leaning to Love Artt through tthe Eyes off

Faith. Foreword by Makoo Fuimura – Christia Scholar’s Review <Loved it!