That sense of nagging fear

There is a nagging fear I experience sometimes. I’m tempted to attribute it to something earthly and circumstantial – some specific, mundane event or condition that, once solved, will make the fear go away.

But I know better now. This fear is repetitive and familiar. Finally, I begin to recognize its particular qualities – its specific, static drone – together with the only means that are effective to counteract it.

Here are some signs it has returned.

1. I glance in the mirror before leaving the house to adjust my appearance. And I do this not from a love of tidiness or elegance, but from a generalized fear of judgment.

2. I find myself almost unconsciously muddling clear, well-meant words of truth because I fear shadowy, inarticulate retribution from someone – though I can’t tell who.

3. I find myself obsessing over a small flaw or error – maybe a cut on my finger, a mistyped word in an email, or a forgotten appointment – quietly imagining it has set me on a slippery slope toward disaster.

4. And most harmfully of all, I find myself often “hearing the worst” from my husband, colleagues, doctors, or even strangers, and I feel, in response, an unthinking defensiveness. On some irrational level, I proceed as if these people wish me ill. Or even more irrationally, I proceed as if their words bring misfortune to me – as if they speak misfortune into existence. (“Can I help you?” “You look tired.” “Oh never mind; it’s nothing.” All such phrases can be taken in a negative way.)

Reactions like these can be momentary, fleeting, and small – but as they accumulate, they simultaneously reveal an inner disquiet and build an interior habit. It’s a vicious cycle. If left unchecked, these accumulated tendencies swell, and they eventually turn the whole world into a capital-T Threat – a ubiquitous, inescapable space to shield oneself against, to approach with distrust, and to deal with dishonestly and cunningly – because it’s “out to get you.” The world itself gradually becomes something “other,” strange, and dangerous, and above all, “not on your side.”

What, then, is left on “your side” when you (when I) go fully down this path? Nothing. You are left in a place of isolation and paradox, where the self alone is trustworthy, but the self is also consumed by knee-jerk habits and delusions that are fundamentally suicidal in their drive to reject any external correction, nourishment, delight or support.

Praise be to God that I’ve never traveled to the end of this fearful road, but I know people who have. I see people who have. And I notice more and more of them every day.

In my experience, there are a few, main conditions that get this pernicious ball rolling. They lie at the root of the fear, and they stoke its fires. They are similar in type, if not in degree. They are all categories of spiritual instability – tilts in existential orientation.

The first error in orientation is what I call “petty idolatry.” God gives us many good things – including many good things meant specifically and clearly to further His kingdom. But sometimes these things seem so good that they eclipse God Himself in our affections. When this happens, we begin to “wobble” existentially without really knowing why. It can take us (it can take me) a while to realize that the good thing we are working hard to accomplish is actually destabilizing us and causing us distress. This distress is the natural effect of trading a firm, immovable “handhold” for something squishy, evanescent, and shifting – however beautiful and useful it is. And often God allows the distress to be amplified so we will come swiftly running back. (Sometimes, painfully, “running back” means sacrificing the lesser good so that God can have full sway.)

The second error in orientation is related to the first. However, this error is more willful and self-referential. It takes divine gifts not as things to be held lightly and utilized in constant collaboration with God, but as things now controlled and deployed according to one’s own, more-or-less independent judgment.

Sadly, I am very prone to this fault – and I think many analytically-minded people are. Often, when God gives me a gift (an opportunity, a project, a sum of money, or some other kind of resource), my brain kicks into high gear, and I immediately “game out” its optimal use according to preconceived ends. (Preconceived ends usually involve quantifiable things like wealth, eyeballs, access, credentials, etc.) I have to actively fight this game-playing tendency, which fatally substitutes a kind of closed-off, algorithmic thinking for constant openness to the Holy Spirit. Thankfully, if I start to go down this road too far, the nagging fear described above eventually goads me back to the right path.

The error of game-playing control I just described is more severe than the first and often results in more stinging existential destabilization as its effects build. That’s because it blocks out the illuminating, stabilizing Light more fully than the first error did.

A metaphor is in order.

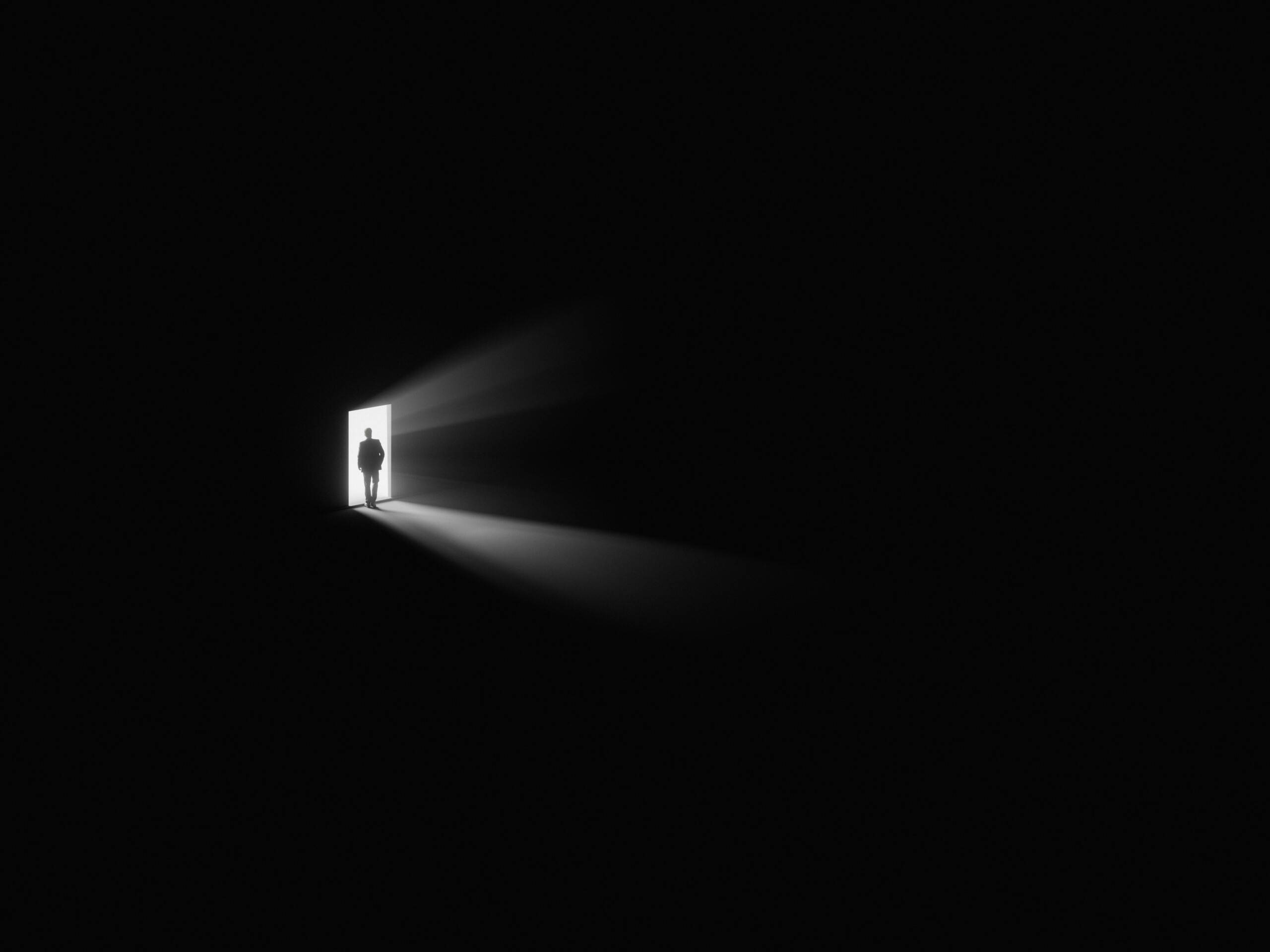

In the case of petty idolatry, one strides toward the Light but becomes distracted by the glittering rainbows in its penumbra and starts to list slightly off course. Nevertheless, one keeps moving roughly in the right direction.

In the case of algorithmic “game playing,” however, it is as if one plucks embers from the Light and then hunches over to arrange them in glowing shapes on the ground. Forward movement is arrested, and the source of Light can at length be blocked or ignored.

In a third and much worse case, however, one runs from the Light because it burns. This is a condition, naturally, of extreme existential destabilization, full of threat, terror and paranoia, and it results in a constant disposition of “fight or flight” – punctuated by self-defensive, manipulative cunning, according to one’s abilities. (Deception is fair game when the whole world feels like a lie.)

This final, radical error in orientation comes from a wound of conscience. The sufferer has lodged inside, as it were, a cold shard of midnight that frantically twists and scrapes when the Light comes near, and the pain is unbearable. So the sufferer runs. In their flight, naturally, they feel spied on and hunted. And because the thing they flee – the “predator” they fear – is Goodness itself, they cannot find even a small corner of safety. Everything becomes a threat. Only the private self ends up feeling safe – but even the private self, in the waking hours of night, is tormented by a corrosive, inner emptiness.

A person in this state walks daily in a phantom whirlwind of menace and even torture, for the good Light burns and the darkness is, well, darkness. Such people, without understanding their plight, begin to experience Hell on earth. And in this day and age, they have little idea why. They cannot locate the root of their affliction.

Why?

First, the trauma and horror of their wound may have sent them into denial. They cannot face what they have done or accept its implications. (It doesn’t take much to incite this horror, if we’re honest with ourselves. Dwell with full vulnerability on a youthful moment when you bullied a younger sibling or joined the “crowd” in taunting a scapegoat. You’ll see what I mean.)

Then second, and more perniciously, our culture does not give sufferers the tools to understand their interior experience. They may have no sense of things like “conscience,” “goodness,” “evil,” “sin,” “repentance,” or even God. They have, in other words, no categories for diagnosing their specific kind of pain.

The result is mute helplessness.

What a tragedy!

There is a moral science that Christian leaders and teachers are duty-bound to share with the world. It is a matter of life and death, both body and soul. Old ways of transmitting this science always become stale and distorted as the spirits of the age discredit its symbols and vessels (strident pamphlets, shrieking street preachers, stern Confessors, bug-eyed prophets of doom). But this science is more important than ever before.

When I was a student at Harvard 20 years ago, I was surrounded by young people with torments of conscience that they did not understand. (Nor did I understand it, then.) A thousand one-night stands, petty thieveries, porn binges, and drunken black-outs (all dishonoring of both self and others) had left twisting shards of darkness in their hearts, straining against the Light. And these young people didn’t know. They were full of pain, but they didn’t know why. Too many of them continued to self-medicate, escape into sensory pleasures, or (increasingly) deflect their inner sense of fear outward toward “scapegoats” near and far. (A propensity toward harsh judgmentalism is almost always a symptom of mute guilt that tries to “pay outward” an inner, crushing sense of doom.)

Now my classmates hold innumerable positions of influence. Are the worst excesses of “cancel culture” really evidence of widespread crises of conscience that externalize their pain?

Of course, it is extremely unpleasant to face these things.

It is unpleasant to attend to the nagging fear that sees judgment everywhere, that runs headlong away from the Light, and that produces severe existential vertigo (for we were all made to walk with God).

It is surpassingly unpleasant to search for the root of these things, as if digging for a deep splinter in an infected sore. Naturally, we resent those who goad us to take a hard look at what pains us. We want to lash out at them. We even want (inarticulately) to punish them in our place. And who wants to be lashed out at? Who wants to be a target of unspoken desperation and rage?

But there are so many delicate hearts so deeply and exquisitely wounded everywhere, all around us, even (and especially!) in Christian settings. They are crying out loudly and constantly on the spiritual plane. And there are so many young ones who have been exposed to traumatizing darkness so early in life – even just secretly on their cell phones, which have been vessels of a million corrosive indignities, internalized and made part of their developing selves.

Almost none of these sufferers (even the Christian ones) have a reliable language to express and navigate the existential fear and suffering that results.

And we may be to blame.

How in this age, can we revive the moral science of salvation? How can we find winsome means to tell the truth about our nagging fears?

How can we tell a story of sin and forgiveness that no longer feels trite, manipulative, judgmental or simplistic – but that nevertheless slices unpleasantly in bracing ways that can’t be ignored?

Maybe it begins with being more honest about how we, ourselves, are afraid.