“In the one Christ, we are one.”

-motto of Pope Leo XIV

The Catholic Church has recently elected a new pope, not quite three weeks after the death of Pope Francis on Easter Monday.

Meanwhile, I have been thinking about Christian education in the city of Seattle, where I teach at a Protestant university and my children attend Catholic school. Seattle boasts two liberal arts universities near its downtown core – one evangelical Protestant (my own institution) and the other Roman Catholic. Are they redundant? Is there a place for both in the current climate? And how do they reflect Christian diversity in our twenty-first-century world?

Let me begin by saying: I am a “cradle” evangelical who joined the Catholic Church five years ago. Though I was drawn to Catholicism by its cultural riches, which I had eagerly embraced by the time I was a teenager, I still consider myself evangelical at the core. (Altar calls, hymns by Charles Wesley, and old-time revival meetings will always be in my bones.) The more distance I get from my evangelical upbringing (which I inwardly sneered at as a young adult), the more appreciation I gain for its outlines, origins, and priorities. Accordingly, after 18 years, I still teach at an evangelical Protestant university. At the same time, I am deeply involved in my Roman Catholic parish, and my children attend our parish school.

Seattle University (Roman Catholic/Jesuit) and Seattle Pacific University (Free Methodist) were founded in the same year, 1891, after the Great Seattle Fire. They were part of a boom that saw Seattle transform from a shambling timber town to a tech epicenter. (Before Boeing, Microsoft, and Amazon, there were typewriters and automatic firearms – partly underwritten by the Klondike Gold Rush.) Both colleges were missionary endeavors, and Seattle Pacific University, in particular, was devoted to shaping people for ministry (it began as a seminary, while SU grew from a Catholic high school). SU (the Catholic one) occupies a central location in Seattle’s downtown core, and SPU (the Free Methodist one) is situated in a leafy suburb just north of the city center. With their similar names and complementary missions, the two schools have gotten mixed up or conflated by Seattleites many times over in their nearly 135 years of existence.

Today, SU (the Catholic one) is much bigger and more prosperous, with more programs and facilities. It is also informed by Catholicism’s deep intellectual legacy, stewarded by the Jesuit religious order. SU recently acquired a (secular) arts school, Cornish College of the Arts, and this acquisition underscores its public reputation as a basically secular school with a religious core – like many other Catholic institutions of higher education. SU builds and equips, often with great richness, but often (I have heard) without clear reference to its spiritual source.

SPU, on the other hand, is a much smaller school with fewer programs and resources. Its spiritual/intellectual heritage is also historically newer, without the range of cultural, philosophical, and methodological riches that hold places like SU together. (Even when belief is absent, heritage builds shared identity and furnishes convenient reference points.) SPU’s comparatively loose tie with heritage, as such, naturally has its pros and cons. It can lead to instability and identity crisis, on the one hand. But on the other, it can lead to nimbleness and innovation. Either way, I think, the cultural newness of places like SPU requires a publicly forthright declaration of religious identity. Without shared heritage and reference, the content of religious belief must be foregrounded; statements of belief provide a connective tissue that isn’t present in other ways.

There are other, more ideologically fraught questions that arise when making comparisons like the one I’m making. Are large, partly-secularized religious schools like SU “sellouts”? And does any kind of secularization indicate apostasy – as if one’s university isn’t “Christian” anymore? Is there a “smell test” for when schools are “really Christian” and when faith affiliation is a historical accident? Or what about the “liberal” and “conservative” wings of American Christianity in our turbulent decade? Is one wing “better” or “purer” than the other? Furthermore, is it possible to classify institutions like SU and SPU in these broadly political (or at least politics-adjacent) ways?

I want to set these questions aside, however, and think about the contrast differently. I am a Protestant who became Catholic, but who still feels “natively” Protestant. And I am wondering: even from a Catholic point of view (that is, from the vantage of the huge, ancient church from which Protestantism split), is it possible to talk about a Protestant genius? Is it possible to talk about a particular gift or charism associated with the Protestant impulse that animates certain spaces? Is it, perhaps, even possible to talk about how a kind of lowercase-p protestantism enriches ancient Christian tradition in a harmonic and complementary way?

The word Protestant comes from the Latin pro testari, which literally means to “testify publicly.” One might quickly associate this term with a missional, evangelical impulse (proclaiming the gospel), but I’d like to think about the term more broadly. “Public testimony” is a concept as old as the hills, and it strikes at a core characteristic of human nature and morality. In short, pro testari captures a bold spirit that takes nothing for granted. This impulse holds everything to the light, before the teeming crowd, inviting challenge and scrutiny. It encourages vigilance, open-eyed awareness and sacrificial recklessness. It is the enemy of complacency and “accepting things as they are.”

Consequently, a spirit of pro testari does not build elaborate edifices upon established “givens” (such as Thomistic philosophy, as at some Catholic colleges). Instead, it demands the constant reassessment of “givens,” toward the end of keeping one’s foundations level, one’s pillars sturdy, and one’s walls anchored in the dirt. Taken too far, this lowercase “protestant” spirit can be both destructive and stultifying, preventing rich growth through a constant disturbing of roots. But when combined harmonically with other impulses (perhaps originating in other places) it can be a necessary catalyst for organic development.

In my art history classes, I often lecture on an essay called “Originality,” by the art historian Richard Shiff.1

In this brief written work (originally an entry for an art encyclopedia), Shiff meditates on the connotations of that multifaceted word. “Originality,” Shiff points out, often connotes “innovation” and “newness,” but it can only do this because it implies a “return to origins.” To make something new, an artist or thinker must “go back to the well,” the ancient nutritive source, and draw something forth that is at once deeply familiar and sparklingly fresh. Perhaps this urge toward “originality,” then, is the true spirit of protestantism – pro testari. It is an urge that says, “Don’t forget to go back to the well! Skins can be carried only so far before being refilled! And water may be sweetened in so many ways, but its pure form is the true medium for new delights!”

Five hundred years after the Protestant Reformation, we know that the ancient churches did not fatally depart from their origins. We no longer believe that the price of orthodoxy and sincerity is cultural erasure (schism, iconoclasm, “purity law”). But at the same time, we see value in a spirit that insisted: “Let there be no complacency! All must be brought to the light! We can’t take official structures for granted but must always keep an eye on the source!” (Let it be noted: The Roman Catholic ressourcement scholars, who informed the door-opening Second Vatican Council, would agree, as would someone like St. John Henry Newman, whose journey to the Catholic Church was experienced as a homecoming of sorts.)

Some minds and hearts, I think, naturally flow with the constant, “re-sourcing” impulse of small-p “protestantism.” They find their vigor in its limpid call to spiritual return.

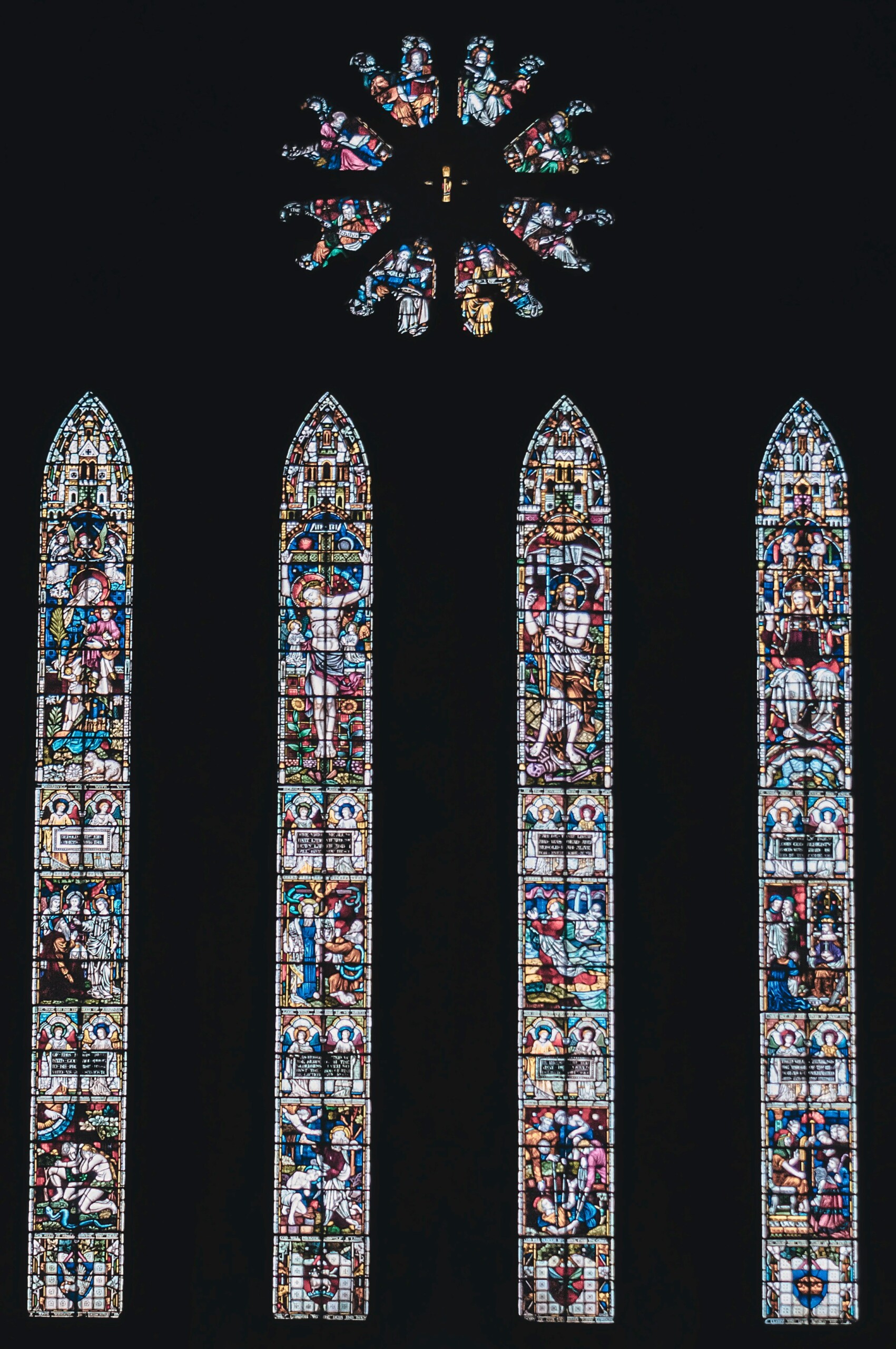

Others hearts, meanwhile, delight in the crafting of filigreed spires that stand, along with their architects, on the literal and figurative “shoulders of giants,” who through patient generations help elaborate energies unfurl.

Each group, each type of thinking, needs the other.

Therefore, in this culture that many call “post-Christian,” in which the Lord purifies and re-sources his pilgrim church in all its manifestations, may we see this fact of mutual need with new clarity. And may we join hands like never before, at once holding to the light (testari) and uniting (katholikos: embracing) in a universal movement of cooperation.

As Pope Leo XIV affirms: “In the one Christ we are one.”

This is a thoughtful and brief article. I am grateful for the insights that were shared. It was also interesting to note that the author is somewhat ambivalent as far as her identity – being Protestant (with a lower-case “p”) and Roman Catholic. It is an all too common error to think the Reformers split from the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, a thorough reading of history will quite convincingly inform the student that the Reformers had no intention of what they were accused of: being novel and schismatic. It was the Medieval church (the “Roman” Catholic ? Church) that departed from the sources to which she added unbiblical traditions and many other such quite questionable doctrines and practices. It was this that the Reformers earnestly sought to discuss, debate, and hopefully reform within the ancient, established church of the Bishop of Rome. And so the cry, “Ad fontes,” and the five Solas. The reading of the well-educated Reformers who translated the Bible from Jerome’s Latin Vulgate and the extant Greek and Hebrew texts exposed and brought to light doctrinal errors the RCC refused to debate and discuss. God’s word was not their authority, the church had the final word on everything necessary to believe for salvation – according to them. The reader must see the anathemas of the Council of Trent, read Holy Scripture, and then decide. I was once RC. I have been Presbyterian for decades, and I humbly embrace Reformed, Covenant, Biblical theology that acknowledges our roots being through the medieval church (RCC), down to the apostles and post-apostolic fathers … to Abraham and Seth and Able, and Adam and Eve. I believe our pedigree is above that of the RCC which departed in significant ways from the faith once for all delivered to the saints. I also believe there are members of the RCC who are indeed united to Christ, who put their sincere faith and trust in Him alone for their salvation … not in any man-made traditions or unbiblical doctrines, or in any institution for the sake of that institution’s claim to authenticity via apostolic succession or anything else. I sincerely and humbly hope this may clarify some things and encourage others to look, see, ask, and receive answers to things that matter, just as it seems you have and are doing.

Is He Lord of each one? Is there spiritual vitality in each person, evidence of each one’s active fellowship with God as each one walks in obedience to His word? If Christ is not Lord of my daily life, can my unity with others, whether each refers to themselves “Catholic” or “Protestant”, be genuinely Christian?

St. John Paul II said that the ecumenical movement should be more than a mere exchange of words; but an exchange of gifts. We need each other’s strengths in a common stand against the spirit of the age.

Thank you for this article. I am a Christian who believes in the saving grace that Jesus Christ life, death and resurrection made possible. I am very happy with your explanation of the origin of the term protestant, though I see myself as a Christian. Now, my question is how you have handled the issue of idols in your new faith? How have you handled the concept of disciples using their meal time to remember the atonement and the grace of being included in the new covenant? Would say the word the written word of God is the light for your path and lamp to your feet (Psalm 119:105)? Yes the Protestant University does not have many needed resources , but I hope that ther are genuine disciples of Jesus Christ who depend on the power of the Holy Spirit more than the systems in which they worship and live.