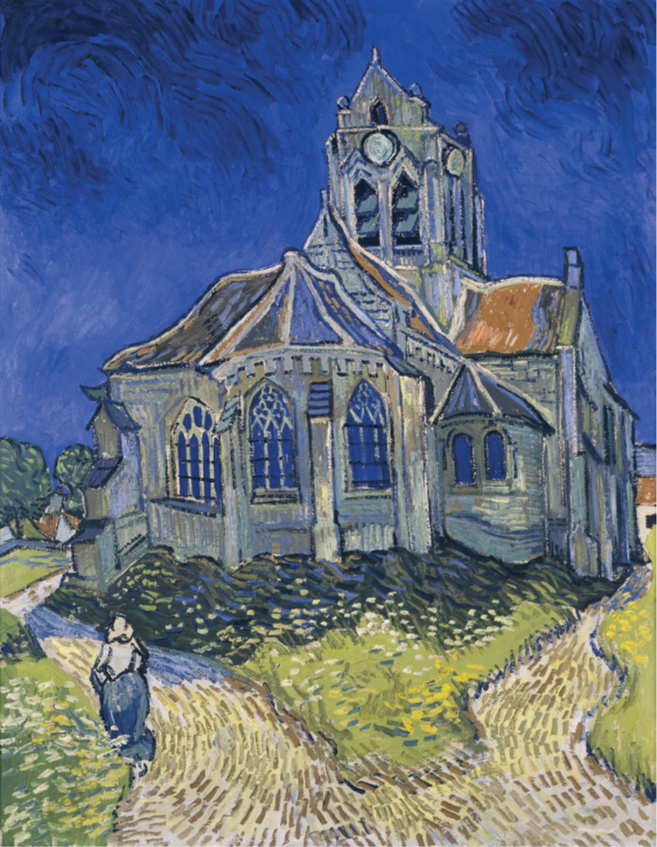

In 1890, not long before his apparent suicide, Vincent van Gogh painted a picture of a church. Van Gogh had recently moved to the town of Uver from san-remy-de-provence, where he had been in a mental institution. In Uver, van Gogh hoped to receive help from Paul Gachet, a doctor known for his compassion toward artistic types. (later, Van Gogh would immortalize Gachet in a famous portrait.)While in Uver, Van Gogh became moody and reflective, often revisiting memories from his childhood. His painting of the Gothic church nearby was a product of this mood, as the artist hinted in a letter to his sister: “It is nearly the same thing as the studies I did at Nuenen.”1 Nuenen, for all intents and purposes, was Van Gogh’s hometown, where his earliest memories had been formed, and his first artistic experiments had emerged. Here, at the end of his life, Van Gogh was revisiting root traumas and memories. His aforementioned painting shows this: under van Gogh’s brush, the church at Auvers is transformed from a building into a living thing, pulsing with brooding personality and weighty life history.

Figure1. The Church at Auvers, 1890 Image Credit Vincent van Gogh, The Church at Auvers, Google Arts and Culture / Creative Commons

Both academia and popular culture have long been obsessed with the elusive Vincent van Gogh, starting with some blockbuster retrospective exhibitions in the early twentieth century. Why? I think it’s because van Gogh’s work is so richly suffused with the artist’s unique perspective. One gets a palpable, agonizing sense of Van Gogh’s turbulent, earnest personality from his work, and that promise of intimacy and disclosure is captivating. Van Gogh shows us that perception isn’t simple. That we bring baggage to everything. That our most unexamined beliefs are actually hodge-podge assemblages of memories, traumas, hopes, wounds, and longings.

* * *

A few generations after Van Gogh, the Christian apologist and literary scholar C. S. Lewis ruminated on perspective in a different way. Specifically, he considered a certain kind of perspective we call “prejudice”—that is, an unthinking inner disposition that makes quick and decisive judgments. (When asked why he harbored a prejudice against the French, so the story goes, Lewis replied, “if I knew why, it wouldn’t be a prejudice!”2 ) Helpfully (and, I think, compassionately), Lewis defined prejudice as a “watchful dragon” that protects us from information that would challenge or disrupt our sometimes-precarious lives. It is a “safety feature” of the human brain, and thus not intrinsically evil—but it can also go awry, blocking us from seeing the good things right in front of us.

In the late 19th century, artists like Vincent van Gogh used techniques of deep, meditative artistic engagement to reveal how humans form perspectives on the world—whether they are understood negatively as prejudices (“prejudice” often implies enmity) or just lived vantage points, from inner watchtowers, built “brick by brick” over periods of long exposure to challenges, punishments, rewards, threats, and lures. From his vantage point on a French lawn, Van Gogh suffused an inanimate building with attitudes and meanings; he revealed inner processes of inescapable and complex judgment, worship, attraction, and repulsion. During an age obsessed with documentary photography (and the camera’s “objective” eye), van Gogh showed that everything is more than it appears.

* * *

Many theorists and philosophers, particularly in the twentieth century, have tried to develop language around the complexities of perspective, as we have been exploring it: that is, the ambiguity, the instability, the depth, and the implications, brought to subjects by the perceiving eye. As the cultural critic and semiotician Roland Barthes observed in his famous Mythologies, everything is both its functional, physical self and also a host of significations and associations that transcend the functional and physical and bear sometimes profound meaning. Beauty, glamor, prestige, comfort, sentiment, and security (or alternatively fear, intimidation, threat, obscurity, exclusion): all these feelings and more suffuse the physical objects we encounter every day. Ultimately, our objective “perceptions” are inseparable from the memories and emotions we bring to every embodied encounter.3

Inspired by the work of Vincent Van Gogh and others, meanwhile, some twentieth-century philosophers began to explore the holistic ways that experience, memory, and desire affect our perceptions (and actions) as we move through the world. The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, for example, observed how the things we call artworks betray a fraught, embodied perception of things—a perception that comes with rich, multisensory paraphernalia. As Merleau-Ponty showed, most notably through an analysis of Van Gogh’s famous painting Shoes, artistic representation is encrusted with the traces of physical memory-imprints, equally strong physical deprivations, and learned, ingrained responses with their own unique textures.4

Figure 6. Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, 1886

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, Creative Commons

The Christian, neo-Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain, finally, gave a spiritual dimension to insights like Merleau-Ponty’s. For Maritain, the “baggage” displayed by sensitive artists in their work was not only the product of ingrained memory, habit, and formation, but also the product of an ontological porousness that had its root in the spiritual connectedness of all things. Sensitive artists (among others) experienced the inner meaning of things through a kind of spiritual empathy, and the intensity of these experiences resulted in simultaneously profound and highly personal records of the things’ true, deep meanings. Paradoxically, for Maritain, this achievement of depth and true knowledge had to be highly personal and idiosyncratic because it depended for its very existence on profound, in-the-moment, existential participation.5

* * *

I am an art historian, and I think it can be argued that the great moments in art history have been defined by shifts in “perspective”—both figurative and literal. It could be said that the great art of the Italian Renaissance emerged from efforts to correct “prejudicial” attitudes toward the themes and heroes of Scripture. There was a sense, perhaps, that the old stories and the old rhetoric had acquired a kind of “mummified” sameness, with characters that were flat and distant. In Germany and Northern Europe, where the Protestant Reformation would take root, the yearning for a new perspective took the form of Scripture in the vernacular, bold new social experiments, and efforts to relive or revive “primitive” Christianity free of medieval encrustations. In Southern Europe, however, these efforts were channeled into the built environment and the renovation of devotional practices, including practices around image and story.

Accordingly, in Italy, St. Francis of Assisi staged the world’s first “living Nativity scene,” which he hoped would “bring the Bible to life” for a disaffected audience. Francis’s genius for immersive storytelling was taken up by Renaissance artists like Giotto di Bondone, who introduced approaches to pictorial light and space (in the context of large murals) that helped you feel like you were “there.” In Italy and other parts of Southern Europe, this thrust toward immersive visual environments continued apace for centuries, culminating in the work of artists like Caravaggio, who used stage techniques from the emerging genres of theater and opera to make viewers feel as if a drama was unfolding before their eyes—albeit on canvas. In his famous Calling of St. Matthew, still in situ at the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, Caravaggio even took the step of dressing St. Matthew in the doublet of a 17th century dandy. The goal was to make the Bible contemporary, to make Jesus viscerally present, and to show that the dilemmas of Scripture still applied to the people of his day.

* * *

The power of art to shift perspective also explains history’s intermittent outbursts of violent iconoclasm, or image destruction. Today, we heatedly debate what kinds of information or imagery should be censored on the internet, and we navigate the implications of so-called “cancel culture.” In earlier times, however, iconoclasm could be a matter of life or death, destroying not only objects and careers, but the lives of opponents.

Iconoclasm—which we can understand as an erasure of threatening perspectives—is as old as human civilization. In the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean, disgraced regimes or defeated rivals could be subject to what the Romans called damnatio memoriae (“damnation of memory”)—a comprehensive program of primarily visual eradication. Every trace, every image, of the unwanted party was defaced or destroyed, lest the “perspective” it represented contaminate the new order. An example of damnatio memoriae: The Severan Tondo, showing the removal of the childhood face of the deposed Emperor Geta. (The tondo depicts, clockwise from the top left, the Roman Empress Julia Domna, the Emperor Septimius Severus, and their heirs Carcalla and Geta.)

FiGURE 2.Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1600 Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew, Creative Commons

Later, in the early Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire hosted decades of Christian iconoclasm—ostensibly in response to theological disputes. But historians have also noted that waves of Byzantine image destruction were linked to political maneuvering toward powerful Islamic neighbors. (Islam has a strong aniconic—or “anti-image”—tendency, going back to foundational Hadiths.6 ) Other historians, meanwhile, have linked Byzantine iconoclasm to the purposeful disempowerment of largely illiterate peasant populations that expressed themselves through imagery rather than words.7 By eliminating certain devotional perspectives and practices in the 8th and 9th centuries, Byzantine rulers could enforce (or so they hoped) a more unified, purified worldview that strengthened the aristocracy in a delicate time.

The Protestant iconoclasm of the 16th century, meanwhile, took on a unique cast relative to these earlier manifestations. In their search for a new perspective (and in their contestation of the old), Protestant iconoclasts stripped art from churches—both inside and out—sometimes with theatrical flourishes. Their purposes were manifold: to cleanse the Christian imagination; to stick it to hated authorities; to reorient Christian priorities away from luxury and opulence; to remove temptations toward idolatry; and more.

Figure 3. Anonymous, Severan Tondo, c. 200

© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro

Anonymous, Severan Tondo, © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / Creative Commons

But the perspective-making endeavor—the artist’s impulse to map “the view from here”—is an energy that can’t be suppressed. Consequently, many Protestant communities instinctively delved new channels in which creativity could flow. The perspective-shaping role of art now shifted from the public sphere (where it once adorned town squares and cathedral facades), into the private one, where individual consumers decided which perspectives they wanted to consume in their home spaces. The golden age of Protestant painting is one of expansive, idyllic landscapes; bawdy pub scenes with voluptuous barmaids; and dining room tables covered with rich foods and exotic bric-a-brac. The shared (and perhaps overbearing) perspective of medieval visual culture gave way to attention to one’s personal delights—and a concomitant introspection, as the portraits of Rembrandt soulfully show.

Figure 4. Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Jan Six, 1654

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Jan Six, The Yorck Project / Creative Commons

* * *

The totalitarian regimes of the early twentieth century knew that art was crucial for shaping perspective. For their brave new social experiments to succeed, these regimes had to suppress alternative perspectives—sometimes with unimaginable brutality.

So how do you uproot and redefine the memories of a whole people? How do you, “knowing” a New Truth, imprint that truth in the minds of millions, unquestioningly? Early Chinese Communism attempted

Figure 5. El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 1919

El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, Creative Commons

to do this through the so-called Cultural Revolution, a ten-year campaign of political executions, institutional closures, and cultural destruction (including the destruction of libraries, temples, palaces, and artworks) that hoped to “reset” the Chinese mind. Early Soviet Communism, meanwhile, took the interesting step of inventing an entirely new art movement that would supplant unwanted cultural forms: Soviet Constructivism. This movement, a pioneering incubator of totally abstract art, aimed to “purify” Soviet visual culture of every kind of storytelling or symbolism that propped up the old collective memory. In place of elements from folklore, tradition, religion, and monarchy, Soviet Constructivism offered abstract shapes that (the artists hoped) would summon pure, unadulterated, progressive energies.

For, as we have noted, one’s perspective on the world is rooted in memory. From the moment of our birth, we acquire memories (first hazy, then sharp) that shape our mental foundation. They populate our minds and are the most important raw matter by which we make sense of the world. When we experience something, it imprints on us, and we move forward from that moment ever asking (albeit subconsciously): “How much is this new thing like the old thing that dwells in me?” Our earliest memories are baselines, launching points, gravitational centers. Later memories elaborate on those baselines, adding flourishes and ornaments in our life-long quest to map the world “outside.”

But we live in a fallen universe, and the memory-baselines we establish are never quite solid and true. Thus sometimes, by God’s grace, we must endure violent inner paradigm shifts, where old memories are redefined in service to greater, dawning realities. These new realities can shape our minds in painful, stretching, unexpected ways, and they can cause inner “earthquakes” with lifelong aftershocks. Regimes like Maoism and early Soviet Communism stepped in to create such “earthquakes” artificially, under the hands of rulers who knew the shaping of government entailed the shaping of the collective imagination.

* * *

It is commonplace to say that art helps you “walk in someone else’s shoes.” Many famous novels, artworks, and films fostered change by helping audiences inhabit a new perspective. The novels of Charles Dickens helped middle class Victorians see the world through the eyes of tormented orphans and put-upon office clerks. The Black painter Henry Ossawa Tanner helped Reconstruction-era white Americans understand the dignity of African American culture at a time of crippling backlash against the Great Migration. And that spiritual shape-shifter Leo Tolstoy, in his unparalleled epic War and Peace, inhabited the perspectives of dozens of figures, from myriad demographics, on both sides of a bloody conflict (Napoleon’s invasion of Russia). In War and Peace, there are no heroes or villains. There are only flawed individuals grappling with the complexities and turbulence of life. Famously, Vincent van Gogh helped us “walk in someone else’s shoes” with his painting titled just that: Shoes. Made in 1886, this canvas hoped to summon years of toil in one, poignant image. It became one of the most analyzed paintings in art history, inspiring philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida.8

* * *

For years now, social commentators have noted that our world suffers from a lack of shared perspectives. Fewer and fewer of us have stood on the same lawn, under the same waning sun, looking at the same church. Fewer and fewer of us have lustily sung the same hymns (of celebration or mourning), feasted at the same tables, or walked the same pilgrim trails. Fewer and fewer of us have haggled at the same open-air markets with our neighbors—the weaver, the baker, and the farmer. Heck, we don’t even have “watercooler” tv shows anymore!

Instead, with so many niche cultural options at our fingertips, we retreat

Figure 6. Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, 1886

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, Creative Commons

into antiseptic, self-designed bubbles of buffering entertainment, curating individual “perspectives” that have little to do with anything but ourselves. Not surprisingly, then, we increasingly lack the ability to “walk in the shoes” of even our next-door neighbors. Our distrust grows. Our bespoke little home-worlds are all we know, and everything else is a threat. The beliefs and positions of others are unintelligible to us because our sense-memories are shrunken and our imaginations atrophied. Enemies are everywhere.

As Vincent van Gogh knew, the thing we call art is an impossible attempt to traverse the distance between persons, between souls. It is an attempt to communicate between textures of memories. It says, “I see you there, and I will try to show you what I am—what I see.” True art does not say, “join in this cause,” or “help in this task,” or “attack this enemy.” Instead, it says, “It is like this,” or “This is what I am,” or “This is what exists.” If we cannot discuss these things, how can we discuss lesser ones? If we cannot come to peace on these things, how can we know what action to take in the world?

* * *

The recovery (or development) of such crucial “communication” muscles isn’t easy. It’s not like taking a rose-colored “Art” pill with your other vitamins in the morning.

It’s not enough, for example, to decide to “support the arts,” and attend a Shakespeare play every once in a while. For one thing, this piecemeal approach ignores the power of deep context. (Attending the play doesn’t mean you understand it!) But more importantly, this approach denies the fact that we’re all already immersed in art at every moment of our lives.

As I type this essay, I am sitting on “art” (my leather reclining chair); I have “art” in my peripheral vision (a John J. Audubon print of Atlantic puffins; a stained-glass Tiffany lamp); and I perceive “artful” graphics flickering from an alternate browser window on my computer (something about Meghan Markle). All these things are forming me, whether I like it or not. To actively consume Shakespeare as “art” while consuming everything else passively is to behave in a curiously lobotomized and dissociated way. It is also tantamount to ceding personal responsibility to strangers and algorithms. How are we allowing ourselves to be spiritually formed, silently and deeply, by the manifold things we unconsciously consume every day?

Perhaps then, we should intentionally and comprehensively consume the “right” art! It’s not enough, after all, to watch a highbrow play every once in a while. Maybe a fast from social media is in order. Maybe some of our “guilty pleasures” (certain novels, certain films, certain websites), need to be removed from our cultural diets. Maybe research is demanded: research into what is most ethical, most correct, most theologically unobjectionable. Maybe high vigilance is necessary to make sure everything one is surrounded by is “pure.”

But these impulses, while laudable, betray a misguided goal. First, the quest to consume only the “right” things is legitimately crazy-making. (There’s no way to identify and purge all the potentially objectionable content from our surroundings, I think we’d all agree.) But second, these impulses, taken on their own, are too surgical, too calculated, too inorganic, too dismissive of human nature. They put the cart before the horse. That’s because our fundamental purpose in life is not, in the end, to form ourselves. Instead it is (of course!) to “love the Lord our God with all our hearts, all our souls, and all our minds.”9 If we are focused too fixedly on self-purification, or even just righteous “self-formation,” we are looking in the wrong direction, and thereby implicitly erecting an idol. Formation must be in service to love, not love in service to formation.

But there is one more promising approach to consider—one, I think, that is implicitly favored by the “arts” academy as well as by “intellectual types.” This approach aims toward the cultivation of peerless cultural literacy, adaptability, and openness through the learning of subtle creative and analytical techniques and cues. Someone who deeply understands Shakespeare, the Bhagavad Gita, the poems of Rumi and the Sistine Chapel ceiling is someone who can move fluidly among viewpoints, converse with a wide range of people, imaginatively enter a range of cultural contexts, and begin to navigate a range of geopolitical issues.

But then the question becomes: to what purpose? Cultural literacy is a start, but sometimes it can become an end in itself. Sometimes it can leave one paralyzed amidst a host of competing beauties.

* * *

I think the best way to consume “art,” and to develop perspective, is to proceed out of love for one’s own givenness, in God’s providence. What do I mean by “givenness?” I mean one’s positioning in space-time, with all its limitation and specificity. I mean the problems one is given to solve, even if they feel like distractions (often our “distractions” are actually the most important things we tackle). I mean the neighbors we live next to, whether we like them or not. And I mean the passions that are implanted in our hearts. A soul motivated by love will use art strenuously and earnestly to navigate the particularities of her “givenness” and will choose art that helps her understand this sacred terrain. The art I need the most is the art that helps me understand my particular neighbor’s humanity—especially the neighbor by whom I’m perplexed, or with whom I’m in conflict. The best art for me to consume is the art that helps me truly, strenuously, earnestly, create a bridge across contexts, across life experiences, across persons that can effect reconciliation and knit together the parts of Christ’s body in my surroundings, living and sprawling, straining and pushing, and yearning for eschatological unity.

For “art” is not entertainment. (The idea of art as “entertainment” is a relic of modern, ideological individualism that tries to excise ultimate meaning from public discourse.) Nor is art, primarily, something to “relax” in front of, to receive vicarious pleasure from, or to pull “warm fuzzies” out of (like Hallmark movies). Finally, “art” is certainly not meant to flatter our intellects (like obscure, theoretical gallery installations or twisty “prestige” films). Rather, as we have seen, art both shapes and reveals perspective, in an absolutely crucial way. It forms worldviews and imaginations, and it creates paths of communication and understanding across chasms. In addition, as we have noted, it is omnipresent. It is absolutely everywhere.

* * *

Amid the little, rolling hills of Southern Indiana, there flows a stream. It traces a low channel among rocky hillocks of red earth, cornfields on little plateaus, muddy escarpments dotted with cliff swallow nests, and sandbars rich with gravel and igneous rock. It flows by ruined barns, their walls tilting precariously; it flows by old men grooming huge yards on riding lawnmowers; it flows by the mouths of limey caves exhaling a cool, sallow air. In the summer, its burbling sound is totally obscured by the hum of wasps and locusts. Sometimes, one finds a dead thing in the brush by its bank, covered with flies, and one thinks inescapably of the power of death and time and the smallness of everything that walks in the world.

People born in this place, who grow in this place, who die in this place, experience the world a certain way. They know certain things because of the memories that have been planted in them—memories of dead things and flies; of clammy caves; of wind blowing through cornstalks; of locusts and lawnmowers.

And then there are the old family cemeteries, with no one left to tend them, sitting bashfully amid patches of alfalfa or soy, untouched out of silent reverence.

* * *

Seven thousand miles away, there is a different place. It is packed with tens of millions of people whose activity never stops, even in the middle of the night. Its ground is everywhere paved gray, and its people walk, in their clusters of thousands, amidst tall, uniform gray buildings with hundreds of identical balconies. On the ledges of these, there are towels drying, or maybe mats. Behind each balcony opening, there are sizzling sounds and smells that compound through the yellowish air. In some places, the sky is blocked entirely. Street vendors call out loudly, promoting their goods. Dust flies up from the ground, everywhere, and everyone’s legs are dirty. Squawking comes from faraway birds in cages. Filthy mattresses are laid on sidewalks with half-naked men lying on them, shoeless, resting for a moment, bathed in sweat. Around a corner, the red-painted stile of an old gate, remnant of an earlier age, leans, unobserved but unmolested. There is a little Buddha at its base.

What do you know if you are born in this place, if you die in this place? What do you know about time and space and action and noise and the give-and-take of life? How do you conceive of the God that has made it all? What perspective do you bring to your own space-time moment, looking at the world from your own two eyes, held up by your own two feet, moving on paths that no other soul will ever traverse again in quite the same way, even if the universe lasted forever?

* * *

Meanwhile, there are certainly counterfeits. There is art that lies—art unworthy of the name. This “art” lies about human nature; it speaks of experiences that never existed; it glows luridly (though perhaps, attractively) with Luciferian dissonance. There are pictures that show smiling people doing terrible things; they want to convince you that you will smile, too, if you emulate them. These pictures activate memories of joy and accomplishment to coerce us. It is important to recognize these things as bulls**t.

But this isn’t a reason to give up, or aggressively censor, or walk the world in perpetual, wary distrust. For almost everything has a nugget of desperate, deeply-felt truth, if one has eyes to see it. And these “nuggets” (or more, when the work is honest) have the potential to build bridges and heal wounds.

For I think engagement with true art—the true, honest, vulnerable communication of embodied perspectives—must precede all other kinds of social negotiating. It must lay a groundwork for other kinds of action in the world. When I treat with you, cooperate with you, arbitrate with you about the distribution of resources, how can I know what is just if I have not known you? You become a mere quantity to me—a quantity that demands mere quantities from me. I cannot think clearly; I cannot see clearly. I lapse into robotic calculations more worthy of blind algorithms than of a free and dignified child of God.

And He is a God who summons delightful, creative power into this pulsing field of surprise He is ever (re)making. Today’s generative algorithms synthesize data from the past. In God, every moment is new.

* * *

The church Vincent van Gogh painted at Auvers in 1890 still exists. And, thanks to the town’s state of historical preservation, it’s easy to identify exactly where Van Gogh stood when analyzing his subject. A quick Google search, in fact, reveals photographs of the church from precisely van Gogh’s angle, pinpointing the great artist’s perspective exactly.

It should go without saying, however, that when considered side-by-side with the aforementioned photographs, Van Gogh’s painting seems to be from another planet. For there is perspective, and then there is perspective. A single point in space can yield one, precise viewpoint, but it’s an incomplete one. As we have noted, memory, emotion, association, ownership, love: these things also create “perspective”—perspective that transcends the limits of space-time and calls a host of other dynamics into play.

The “real” church at Auvers (known locally as Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption) is a compact, rectilinear structure with a cruciform (that is, cross-like) architectural footprint, a central belltower, and a few curved apses projecting from the main structure. It appears stable, weighty, and relatively simple compared to many churches of the Gothic era. Constructed of yellowish local stone with roof tiles of rusty brown, it gives an impression of muted warmth and quiet austerity.

In his painting of this church, however, Vincent van Gogh bears witness to a different kind of reality. First, the darkened church (rendered in cool grays) seems to rise and loom over its golden landscape in a vaguely threatening way that doesn’t quite correspond to Auvers’s topography. Second, the walls of the old church seem to buckle and undulate, as if the structure is breathing or stretching; it seems to be uncannily alive. Meanwhile, the tall, graceful windows of the church are rendered in a deep black, making the structure appear somehow blank-eyed. In sharp contrast, the sky behind the church throbs with a brilliant, almost preternatural blue.

The building we see, in van Gogh’s painting, is clearly not “just” a church. Instead, it is a “living” symbol of majesty, judgment, beckoning, rejection, and many other things known only to the tormented artist as he made the image. (It’s worth remembering: Van Gogh was once rejected from the pastorate.) An eccentric and loner, whose erratic behavior drove away his closest friends, Van Gogh made art to assuage his personal sense of isolation. He needed to bridge the gap between himself and others. He needed to show people how he felt, and why he was different. He needed to trace a “view from here” that could help others, at least for a moment, stand shoulder to shoulder with him, looking at the same reality. His paintings call across time for empathy and fellow-feeling. He would be dumbfounded, today, by the millions who would say, “his work captures what I feel.”

* * *

Earlier, I mentioned Henry Ossawa Tanner, a Black American artist whose work expressed a fresh perspective in the wake of the Civil War. Born in the abolitionist North, Tanner was the son of an African Methodist Episcopal bishop. He would also be among the first Black Americans to receive a world-class art education, which in the late 19th century could only be acquired in Paris.

Sensitive and self-aware, Tanner noticed everything, felt everything. In his autobiography, he wrote about his acute consciousness of “not being wanted” in elite art spaces, despite his obvious talent. He also wrote of the enduring trauma these experiences engendered—trauma that pricked his memory and emotions decades later.10 Tanner knew what it was like to be misunderstood, underestimated, and outnumbered. And he also knew that such experiences were (to varying degrees) universal. Over a course of many, fruitful decades, Tanner used his art to build bridges across racial, national, and historical barriers, helping sensitive viewers make connections across contexts and “walk in others’ shoes.”

Two of Tanner’s paintings especially stand out, to me, as profound and bridge-building, with the power to shape imagination even a century after they were made. The first, titled The Thankful Poor, hails from the middle of Tanner’s career, after his education in Paris and his development of a narrative style that would connect French Impressionism with the “Ashcan” style of early-twentieth-century American modernism. Suggestive, bravura brushstrokes, homey detail, and an earthy color palette combine to give a fresh take on corners of human experience usually neglected in the world of “fine art.” Here, two family members (one suspects a grandfather and grandson) offer a prayer of thanks before a humble meal. They are Black Americans, probably hailing from rural Appalachia. And their meal is notable for what—and who—is missing. There isn’t much food on the table.

Figure 7. Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Thankful Poor, 1894

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Thankful Poor, Creative Commons

But more to the point, there is an entire, absent, generation. (“Where are the child’s parents?” One can’t help but ask.) This moment of thanks takes place downstream of tragedy. But it is also suffused with a quiet dignity, rooted in faith, that stirred open-hearted audiences with feelings of solidarity and empathy.

A second, remarkable painting by Tanner (and one I use in several of my courses) is his Annunciation, painted in 1898. This painting, along with many others of biblical subjects, seems to have emerged in the wake of a religious experience that prompted Tanner to commit himself anew to his faith. Indeed, beginning in 1897, Tanner would spend a year in the Holy Land (on two separate sojourns), learning, a bit, to walk in Jesus’s shoes.

Tanner’s Annunciation, depicting the moment when the angel Gabriel approaches Mary with a cosmos-shaking proposal, is one of the most remarkable versions of this subject in the history of art. First, Tanner has placed this supernatural event in the humblest and grittiest of dwellings, complete with chipped, earthen walls and a rutted floor. Second, he has conjured a wonderfully lovable and relatable Mary, whose demure posture shows just the right combination of holy fear and trembling openness, and whose clasped hands remind one not only of prayer, but of wondering reticence and self-protectiveness.

It is the angel, however, that stuns one the most. Tanner’s Gabriel is neither a sweet-faced cherub nor (as was more usual) a strapping athlete in a fluttering toga.

Figure 8. Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1898

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, Creative Commons

Instead the announcing angel is a pulsing rod of light. What a novel conception of God’s spirit messengers, who, after all, are not enfleshed as we are! One is put in mind of C. S. Lewis’s eldils in his Space Trilogy (among other things), and one is also inspired to reflect on the shape of the universe, the meaning of message, and the laws of physics when it comes to the works of God across the barriers of being and existence. This is a bracing picture that helps refresh, just like Giotto did 700 years before, the Christian imagination in its question to understand salvation history. Henry Ossawa Tanner could paint this picture because he knew awe, he knew humility, and he knew redemption—deep down in his bones. These were part of his lived perspective, and he knew how to translate them in ways that others could see.

Hindu tradition relates the story of the “Blind Men and the Elephant.” Each man grasps a different part of the great beast, and so each man thinks he is grasping something different from his peers. Of course, all their perspectives are correct, and each perspective is needed for a total “grasp” of the whole.

But in the parable, the blind men accused and argued. Today, we do the same thing. Not only do we struggle to empathize with others’ perspectives, but we are not even aware of the angles and limitations of our own. We are not even aware of the experiences and stimuli (some malignant) that comprise our outlooks and inform our decisions. This places us in a fog, as it were—wherein we bump into shrouded things, hidden things, and curse them for giving us bruises, hardly grasping their dignity or even glory.

A sensitive openness to the thing called “art” can be a first step toward exit from this shrouding, this illusion. By opening us to difference, it can make us aware of the contingency of our own situation—on a lawn outside a church, in a concrete high-rise, in an Appalachian village, in a war-torn empire. (What is your “view from here”?) The first step is to open our eyes and stop taking things for granted. The second step is to walk the hard path of gesture, communication, and evocation, which can be a path of confusion and pain. (Sometimes, when we don’t understand something, it’s because we don’t understand the depth of pain it evokes. If we ask Him, the Lord will give us the empathy to experience this pain and gain “eyes to see.”)

All these practices build bridges across persons until, in the fullness of time, all will be connected and gathered to the same destination, sharing the same, sublime object of contemplation, approached from manifold perspectives, captivating every consciousness. Hailing from every age and nation in history, we will behold the same beatific vision, the same slain lamb, the same crystal sea, the same heavenly throne.

Cite this article

Footnotes

- Vincent van Gogh, letter to Willemien van Gogh, June 5, 1890, letter 879, Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (Van Gogh Museum; Huygens ING, 2009), https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let879/letter.html.

- This widely recounted anecdote is part of the oral history around C. S. Lewis. It was related by Lewis’s friend, Walter Hooper, in a lecture at Oxford University on Sunday, November 24, 2013. For a synopsis of the lecture, see Ben Travato, “Walter Hooper on C. S. Lewis,” Countercultural Father, November 24, 2013, https://ccfather.blogspot.com/2013/11/walter-hooper-on-c-s-lewis.html. Other scholars and acquaintances of Lewis also recount this anecdote.

- See Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Paris, 1957). The first English edition was published in 1972, in a translation by Annette Lavers (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux).

- See, for example, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” Art de France 1 (1961): 767–771. The first English translation appeared in The Primacy of Perception, ed. James E. Edie, trans. Carleton Dallery (Northwestern University Press, 1964), 159–190.

- See, for example, Jacques Martain, Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry (Meridian Books, 1955).

- This view is recounted, for example, in the entry “Iconoclasm” in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson (Garland, 1990).

- See, for example, Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art (University of Chicago Press, 1994).

- See, for example, Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 1935 (which can be found in Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter [Harper & Row, 1971], 15–86) and Jacques Derrida, “Restitutions,” 1977 (which can be found in Jacques Derrida, The truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod [University of Chicago Press, 1987]).

- Paraphrase of Mark 12:30.

- Quoted in Dewey F. Mosby, Henry Ossawa Tanner (Philadelphia Museum of Art and Rizzoli Publications, 1991), 60.

One Comment