Aaron B. Franzen

When I look into the face of my enemy

I see my brother, I see my brother

Forgiveness is the garment of our courage

The power to make the peace we long to know

Open up our eyes

To see the wounds that bind all of humankind

May our shutter hearts

Greet the dawn of life with charity and love1

We recently finished up another election season, and for some that went quite well and for others it went quite badly. Some of my students were struggling with the outcome of the election, even to the point of tears, and I kept thinking about how otherworldly and nonsensical that response may be to many others. I wanted to at least bring it up in class to check in with them and see whether they wanted to talk about the outcome. Initially, nearly none of them wanted to talk about it. I told them that it seemed as though it was fairly contentious and that things were unlikely to get better if we remain unable to talk about it. I wanted to take a moment to think through the social processes of that experience.

Students described how conflictual conversations had been and how the vast majority of those conversations were situations where they did not feel as though the conversation partner was even hearing what they were trying to say. Others described a delicate dance where they would slowly feel out the other person to see if a conversation was possible or not. It seemed as though this was another instance of only being able to have a conversation if the other was at least somewhat already in agreement. These conversations and interactions with students about the recent election and my own attempts to make sense of relational conflict became the seeds for the present article.

Over the last few years, many people feel there has been an overall increase in conflict, often having roots in politics.2 For example, on the common temperature scale (warmth reflects positive affect while lower temperatures reflect negative associations or perceptions), ratings of one’s own party have remained consistently warm since the 1980s, while perception of the opposing political party has decreased from about 48 degrees (neutral) to about 20 degrees in 2020.3 This tends to preclude relationships and interactions with others.4 Much of this conflict is affective in nature and not over the contents of policy per se,5 but for the purposes of communal conflict this distinction likely does not matter. A large proportion of our interactions are driven by a preconscious emotional attraction or repulsion, and so this affective orientation that is either positive or negative is influential.6 What I am interested in here is not larger, macro-level conflicts, but the conflict within existing relationships, families, campuses, or other communities where individuals do have the actual opportunity for interaction with others. The problem is that there is a natural feedback loop for conflict that makes it quite challenging to avoid amplification. This poses a real challenge for Christians who are called to be peace makers.7 While there are many examples of the munificent and lavishly generous possibility of people towards one another, conflict can also cause us to fold in upon our selves in a penurious manner; avoiding this possibility must be purposeful.

Here, I give an overview of how feedback loops of conflict function, then highlight how it is challenging to see a path forward within the context of moral diversity in the modern world. I then propose that an orientation of generosity and hospitality may be a way forward. My main interest here is that if people are the end result of a chain of historical interactions that shape any given identity, overt conflict or conflict in the background of interactions will shift people away from what they could have been in the context of a flourishing relationship into what they have become as a result of conflictual interactions through time.

The Process and Feedback Loop of Conflict

While it is possible for conflict to devolve into overt violence, the conflict I have in mind here generally takes on a more benign and stable form instead of physical violence. For example, a college campus community can be characterized by conflictual relations between students with violence never overtly taking place. On the other hand, the absence of conflict does not imply the absence of disagreement, which is often an unrealistic expectation even within the context of committed friendships. The primary difference between the possibility of disagreement within relationships as opposed to conflict is when there is an increase in interest and investment in the other person that shifts them from an interchangeable abstract person into a person in the specific and known.8 It is unlikely one can “know” someone in the absence of some degree of intimacy that personifies the other. When there is an increase in intimacy, the other can be known to a degree that makes their position sensical instead of nonsensical, even if still rejected in the end. Conflict, at least the more intractable kind described below, is to a greater or lesser degree dependent on the objectification of the other, keeping them as they are or imagined to be at a distance. In other words, it is the absence of the commitment to see and continually rediscover a person and then proceed with the interaction or social process accordingly.

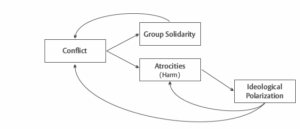

The sociologist Randall Collins, who has written several articles and two books on violence, formalized pre-existent but somewhat unsystematic social theories explaining how conflict works within social groups.9 Conflict within social groups tends to have an inherent feedback loop that amplifies the conflict across time (see Figure 1). This is because real or perceived conflict tends to clarify social group boundaries, driving people back to affinity groups, which in turn tends to further clarify and increase the initial conflict. Additionally, that conflict can, over time and once it reaches certain generally emotional thresholds, lead to atrocities (atrocities in his model are in reference to wider-spread group or identity-driven violence). While Collins’s main interest is in how and when violence breaks out, the same can apply in the absence of actual physical violence with threats, gossiping, slander, or other seemingly benign forms of action against another individual or group. As this begins to happen, not only is the initiator’s group identity and boundary clarified but they also come to solidify perceptions of the opposition. As this “violence” moves towards solidified perceptions of the other group, it tends to, again, feed back into and amplify the original perception of conflict.

Figure 1. The Feedback Loop of Conflict10

There is a certain positive and even necessary role for conflict within society as it tends to resolve tensions within groups and relationships and push people to avoid developmental stagnation. This could have the effect of an increased sense of belonging within a group.11 That is, if “we” are unified in our opposition to some other group, then it can have the effect of strengthening our bond with one another. The cost is that this increased sense of solidarity with one another can have the effect of pushing us into further conflict as the contents of the conflict come to be clarified and more in focus.

The challenge within a community is that it is all perceptual. We rarely verify that the assumptions we have built up about other people or groups are accurate—if they reflect what they actually think or who they are. People merely progress with perceptions and assumptions being “taken for granted” unless something forcibly removes the assumptions from us. 12 This might be a situation where we are no longer able to overlook the incongruence between our assumptions of the world and others, breaking some piece of our “reality” or breaking some perception of the world around us and the people in it. There is the possibility that we come to increasingly perceive those around us through an ideological lens that acts as the filter for our perceptions. This has the tendency to push us further yet into increased conflict. Our taken-for-granted knowledge of others around us becomes, by and large, stable, leading us to avoid interactions with those we already “know” about. This is unlikely to change without unavoidable disconfirming interactions with others outside of something artificial that forces interaction, like a structured psychological study.13

This conflict does not need to result in physical or overt public actions being taken against others. While obviously possible, much of this conflict remains in the background, mainly finding its home in the affective and emotional orientation of some against others. What I have in mind is somewhat subtle conflict that can come off as passive aggressive or sarcastic interactions, sheer avoidance, or other micro indications that friction exists, although it could also become more overt at times. I say this because this is the conflict that likely exists within congregations, workplaces, schools, families, or loose friend groups. This complicates these communities with the natural feedback loop, making it worse. It is possible that none of these relationships have this kind of conflict and exist within a context of homogeneity, but this is likely the result of complete conflict feedback loops that have already pushed out the neutrals, or those who do not strongly associate their self with one “side” or the other, so as to increase the sense of solidarity within the defined group.14

The Complication of Moral Diversity

On the one hand, we could hope for a future that is less ideological and conflictual because we can work towards an agreement regarding what things are “good” and what kind of world we should work towards. This, however, is dramatically unlikely because there is no real way to objectively verify whether one perspective or interpretation of a moral good is indeed better or more desirable than another.15 Claims to objective knowledge necessarily come from within a pre-existing narrative creating coherence. So, one can form claims within any given perspective, yes, but between perspectives this is not the case. This does not, to be clear, mean that there are not ontologically real things, merely that all perceptions of those things are necessarily situated from within some pre-existing structure that gives it coherence, complicating an “objective” adjudication of the claims.

One of the notable challenges about perceptions regarding what we as individuals and collectives should do is that for the most part those perspectives have come to be detached from meaning systems, and are no longer, in the phraseology of the influential moral theorist Alasdair MacIntyre, teleologically driven.16 This is a problem for MacIntyre because there is no longer the same shared basis upon which we can answer questions regarding what it is that we should do.17 Because our ability to process the world around us and be rational are “inherently tradition-bound” and contextualized, and because there are increased social and contextual fractures in these moral backgrounds, there is also an increase in the conflict regarding moral visions.18 And at times this is violent, a point I will return to in a moment.

While MacIntyre leaves us feeling quite skeptical regarding the possibility of reclaiming a shared moral vision for the future, the Anglican priest and ethicist Oliver O’Donovan offers a modified alternative.19 For O’Donovan, the world as it is ontologically does not come to be conflated with what we know about the world epistemologically, which allows him to make claims regarding a right moral vision for the world even though our specific contexts may alter or distort our ability to know or enact that vision.20 We cannot have a view from nowhere, and this leads us to have a vison of the “moral” that is also more or less clear. For this reason, cultural location and context are still important because we are all enacting the stories we find our selves within, even if there is still only a single reality within which those embodied contexts perceive the world. Hence, for O’Donovan, this is the place of repentance and forgiveness: “that is, it is the Spirit which enables humans to respond subjectively to the objective, created order of things which was restored and vindicated by Jesus Christ in his resurrection. The proper form this pattern takes is love. . . . It is the task of Christian ethics, guided by the Spirit, to trace, participate in and so bear witness to this ordering of love.”21

And yet in the midst of an increasingly fractured moral world it can be hard to see past those contextualized perceptions of the world that then shape moral visions of the world. This is especially the case as the groups shaping those perceptions may come to be increasingly smaller, with fewer overlaps, a consequence Durkheim pointed out as a possibility of the modern division of labor.22 As groups come to be increasingly specialized and autonomous, they come to have fewer connections with those dissimilar to their selves. Societies are stable to the degree that they have a shared perception of the world they share, but groups insulated from each other tend to have fewer shared perceptions. This is the place of our present interactions regarding modern American politics.23

An additional and possibly more helpful way to think about this comes from the sociologist G. H. Mead. Mead argued that our perceptions take on significance as any given situation becomes what it is to us as we filter through various possible symbolic interpretations of the situation, and then select the interpretation that seems most fitting.24 The problem is that one can only select from known symbolic interpretations, as they are not really produced on the spot, unless of course there is some dearth of meaning that requires some transposed and repackaged symbolic interpretation to make sense of things. All this to say, interpretive isolation will cause problems in social groups as various situations come to be increasingly meaningless to others. As conflict is the subject of this article, “situation” here is in reference to other persons or groups. It is people or groups of people that come to be increasingly meaningless in contexts of interpretive isolation.

Possible Ways Out of Conflict

Collins does specify a number of ways conflict may fail to escalate.25 First, it is possible that people just come to avoid the conflictual group, which would then shortcut the feedback loop of conflict escalation. This possibility of avoidance is important because it is likely a common occurrence within a bounded community, like a workplace or college campus. Ironically this may just allow the conflict to fester as isolation from one another complicates the possibilities for overlaps in interpretive horizons, just making the ‘other’ more nonsensical.26 The second way that conflict can de-escalate is from the reality that there is a fairly high natural reticence for overt violence that then leaves those in conflict in dead-end feints of escalation that de-escalates from sheer boredom.27 This is, however, probably less prominent within the types of communal conflict of interest here. Third is that the conflictual group could run out of resources thereby ending prolonged conflict. This is possible but may primarily be in reference to others’ willingness to indulge someone or a group for a period in grievance claims. Sooner or later that social or political capital comes to be spent.

The fourth possibility for de-escalation relates to the emotional burden of conflict. Because it takes an emotional investment to engage in conflict, it is possible that people or groups can come to feel burnt out emotionally—tired of the effort or the fight—which would then shortcut and end the escalation feedback loop. This emotional burnout may be the most potent source of de-escalation, and Collins posits that in most cases there is a natural half-life in measurable time whereby this happens in the sense that the ability to maintain heightened negative emotions producing the affective side of conflict is hard to maintain and dies off. I think that this pathway is likely in the communal cases of interest here, but conflictual relations may outlast this half-life because while people may not engage in overt and outright conflict, they likely still, 1) feel the oppositional orientation towards others and 2) may avoid those others as posited in the first point. Both would have a lingering effect within a bounded community that would in totality sap communal vitality. Finally, and related to the prior, part of the solidarity building process is to pull in and build alliances with others, and those alliances could fall apart for various reasons. The fracturing of alliances is likely also viable, but at least in part due to the emotional burnout or exhaustion mentioned above.

For the most part, it is possible there never is an escalation or de-escalation of the conflict and it is merely sustained at a point of equilibrium, like that elephant in the room we continue to ignore. This is the case for most of the avenues just mentioned. The main problem with any of these forms of de-escalation or with equilibrium is that the possibility of a repaired relationship is at best incidental. They are all more or less different versions of failed conflict with stable negative affect, not reconciled relationships. For the most part the natural feedback loop and amplification of conflict primarily end with exhaustion, not repair—exhaustion of resources, emotions, energy, interest, and investment.

Should Christians not care about reconciliation and the possibility of flourishing relationships and communities over and above mere failed conflict? What is of central importance to me here is that this destabilization of the relationship will manifest itself within the biography of those individuals.28 Stable broken relationships congeal within the person and biography of those on either or both ends of the relationship, stripping away the meaningful life that otherwise could have been. Even conflict in equilibrium will leak out and lodge itself within biographies across time.

Christians are Called to Infinite Love Not Exhaustion

As such, it is my contention here that Christians are called to more than mere failed conflict, more than unsuccessful objectified and ideological labeling of others around us. Christians are called by Christ to love the neighbor, but we often still ask who these neighbors are; who exactly do I need to care about?[29] Kierkegaard argued that love is chiefly defined by its infinitude.[30] Love is not something that can be measured, doled out, quantified, or limited in dependence on others’ response or interactions with us. No, love is necessarily infinite in nature, always seeking the good without asking questions of reciprocity, as the example is Christ who showed his love in the complete loss of himself on the cross.

There is a very interesting section within 2 Corinthians where Paul is encouraging the church in Corinth to financially help the Jerusalem church. Paul tells them about another community that had given despite a challenging context and then tells the Corinthians that they have a lot of strengths—in faith, speech, knowledge, and so on—and that they should be sure that they also excel in generosity. Here’s where it gets interesting. He says that he is not commanding them but is testing how sincere their love is by comparing it to the earnestness of others, and the other that he compares them to is Christ. He says that Christ made the choice to become impoverished, putting aside his riches, so that they could be rich.

This has been striking to me because it does not seem as though the richness that Christ put aside was monetary richness. Christ chose to step into our humanness and our brokenness so that we could be whole and rich like him. This is notable because we can see that purposefully sacrificing some of our self is what may be the thing another needs in order to be more whole. Others need our munificence and we need theirs. There is something about us that is more impoverished when others do not generously give something of their self to us, and us to them in return.

Andy Crouch, a prominent Christian cultural analyst, argued that flourishing can be best found when individuals and communities have both the ability to meaningfully control outcomes (authority) as well as some level of meaningful possibility of risk or loss; have both authority and vulnerability.[31] He argues that if one has the power or ability to control outcomes in life or relations but at the same time have no or very little vulnerability, then their relations with others are generally exploitative in nature. On the other hand, if all one has is consistent exposure to vulnerability and no real power or ability to control outcomes then by and large the experience or position is that of suffering. The communal and relational response, which seems to be mirrored in Paul’s call to the Corinthian church to demonstrate their love, is to artificially and purposefully increase risk for the betterment of others when there is abundance. No relationship or community can exist for long when one or only a few have all the control and there is little possibility of loss. But at the same time, those same relationships and communities are not stable without an ability to exert the self. The former is prone to abuse on some level, and the latter is prone to objectification and identity loss on the other. Paul’s comparison to Christ was that of one purposefully reducing power and increasing vulnerability so that we can have decreased exposure to vulnerability. This is the call to love the neighbor: risk more of the self so that the other can risk less.

Exhausted or resigned conflict is not an option for the Christian because of the call to love the neighbor where there are no bounds on that call to love. To opt out of relational repair that short cuts the amplification feedback loop or stagnation of conflict is to grasp hold of only power within relationships while avoiding or denying any possibility of vulnerability. That is to say, without relational repair all one is left with is the uncomfortable realization that their own orientation towards the other is exploitation, even if the primary goal is to fight exploitation perceived to be others’ end goal. Flourishing only comes when one reduces one’s ability to control a person or a context and risks some possible loss in reforming a connection.

Abounding Possibilities in Generosity

I was recently thinking about this because during the last Trump presidency I found myself frequently trying to humanize the proverbial political opposition for others. If they were strong Trump supporters, I would try to help them imagine a world where the Trump worldview is scary and at times causes pain. If they were strongly opposed to Trump, I found myself trying to help them imagine a world where those on the other side do not hate them. I did not want multiple more years of the same and found myself reflecting on the story from Mark 12:42–44 where Jesus was watching people put money into the temple treasury. Rich people put large sums in, then a widow came and put a small amount in. Jesus tells the disciples that she gave more because she gave out of her poverty.

In the same way, while at times we feel as though we are too tired to be generous with others, it may be at those times that it matters more. If people are who they are because of their interactions with people through time within a context, then those interactions cannot only be generously oriented when interaction partners feel emotionally full and able to be generous. There are so many times in life when we are legitimately tired; legitimately running on empty. And yet, people are who they are when we either seek the image of God within them or in our exhaustion ignore them, slander them, or in some other way overlook them as a unique person and strip away that imago Dei. That is to say, I am not sure it is an option for us to suddenly grasp for that power over others found in that objectifying distance that also insulates us from the image of God within them; to not take the time and effort to see them as they are and not as we pre-conceive them to be. Objectifying people is the easy path when tired, but our love is shown in that moment.

Obviously, the challenge with this is that it is hard to keep giving, especially when it seems as though there really is not more that can be given. This can pose an existential question for us, as it did Kierkegaard.[32] If love is defined by infinitude and cannot be limited without ceasing to exist as love, and we are called to love the neighbor, the call disallows taking a break. The keen introspective reader should immediately recognize the impossibility of this, and for Kierkegaard this is the point. There is a call by God to do something that we are, at the same time, unable to do. We find that we have failed in this, do fail in this, and will continue to fail in this. The only way through or out of this despair—recognizing the inability to do what we are commanded to do—is to constantly go to God in repentance, where we can receive forgiveness, take up the identity of Christ, and be made whole again.

But we are also, at our best, embedded within communities and relationships. Beyond the individual pattern of repentance and forgiveness that brings new tomorrows, this is also the place of community. Our relationships and communities are there to fill us up, out of their generosity, so that we may as a collective do what we are called to do: choose impoverished selves so that others can be rich as a self. This is related, again, to Crouch’s idea for a flourishing community. We artificially and purposely impoverish our self and reduce our authority to connect with and support others, so that at some point in the future, when the tables have turned and we find our self in need, others are then able to reciprocate this support. In this way there is a dual role for the increase in relational vulnerability: we support those within our community so that they can continue to love and we open our self to those who are also not within our defined communities.

Again, we see these dynamics of communally embedded generosity in 2 Corinthians 8 when Paul is encouraging the Corinthian church to support the needs of the church in Jerusalem. The sincerity of their love was not shown by a feeling or an emotion, although that may indeed be a pre-condition. It is shown by the example of Christ becoming poor so that through his poverty we may become rich. This richness of Christ was, again, not defined monetarily. He willingly took on flesh and stepped into our brokenness so that in his grace we could be whole, rich.

Picking back up with Crouch’s point about flourishing communities, later in that 2 Corinthians passage mentioned above Paul writes,

Our desire is not that others might be relieved while you are hard pressed, but that there might be equality. At the present time your plenty will supply what they need, so that in turn their plenty will supply what you need. The goal is equality, as it is written: “The one who gathered much did not have too much, and the one who gathered little did not have too little.”[33]

Oddly enough, purposeful self-impoverishment for the sake of others leads not to shortages but abundance and stability.[34] Isolation and exhaustion can make us feel as though we must protect what we have left, all the while blind to the fact that this move disallows us from finding the reality of the infinity of love; the munificent possibilities of life that flows from love. Some things, like infinite love, do not decrease but increase in their use. I may be too tired to engage with those “others” today and need those close to me to support me, and at some point in the future this will likely be reversed. We all need our home base—the place that can fill us when we are running low or where we can fill others when they are low. And nonetheless, in the midst of this, we still have the command from our Lord Jesus to love. Communities can never be shaped, formed, stable, or healthy without investment. Without love. Without this investment, the frail semblance of a community can only exist through exertions of power and conflict attempting control. That is to say, a community with no real meaningful or worthwhile connections, merely held together by something akin to an invisible prison of power, sapping at least one key characteristic trait that came with God’s image within persons upon creation: love.

Beyond the place of community, which is and can be the face of God within the world,[35] there is obviously the possibility of God filling us up and sustaining us past where we thought we would be unable to orient our self towards people. One notable example of God’s unpredictable sustenance is the story of Elijah and the widow of Zarephath.[36] God tells Elijah to go to her for food as he instructed her to feed him. When he finds her, she is in such a bad situation that she was going to make her and her son’s last meal, after which she planned to starve to death. Elijah asks her to make him some food from her clearly struggling supply, and she, often like us, seems to have no recollection of God’s instruction. Then in a move I imagine would be hard if I were in her position, she does so: she makes him a meal first and then proceeds to make her and her son’s last meal. After she agrees to put care of Elijah first, however, she finds that her supply is miraculously filled and does not run out.

When we feel as though we no longer have anything to give to those around us and our ability to be generous towards them has run dry, the call to love them does not end. Indeed, we are called to follow the pattern of Christ and give so others can be rich. To be like the widow at the temple and give even out of our poverty. To be like the widow of Zarephath and provide when the supply is dramatically limited. And when we do so, we have faith that God will indeed find a way to fill us. Find a way to make our life, relationships, and community enlivened with the nonsensical call of his love. To orient our self so that we can always see the image of God in those around us, stripping off the ideological residue so that what we are left with is them.

Hospitality as a Way Out of Conflict

This brings us back to the question of conflict within relationships and communities. From within the dynamics of conflict amplification feedback loops, it is hard to see a way out apart from sheer exhaustion, domination, or stagnation. From MacIntyre we can see that in the midst of moral diversity there is no clear path out and sociologically we know that through time groups tend to homogenize and avoid various forms of differentiation, including ideological. This is a trend that speeds up with modern technology, with mediated interactions algorithmically curated.[37] We have no shared background of meaning built into moral perceptions that allows for offramps avoiding conflict. Our social networks may be less dense with fewer overlaps between groups that could otherwise allow for offramps. Care for and investment in those persons and groups on the other end of conflict is thinner.

The future is quite fuzzy, with fewer reasons to expect shifts in conflict cycles that move towards mended relations over fractured ones, and some common possible suggestions seem unlikely to dramatically change things. It may be possible for empathy to change the conflict feedback loop, as it is hard to look indifferently away from pain up close at least in the short term. It may be possible for humility to change it, as humility increases the felt possibility that you have it wrong, and conflict works best with confidence. It may be possible even sheer emotional burnout could change things as conflict requires higher emotional investment. The issue that makes all of these somewhat idiosyncratic and unreliable solutions is that there is no real background meaning stabilizing the approach through time, especially because opting out of conflict amplification takes significant effort. It is possible one is empathetic because one thinks a person should be but it seems that the effort required would need a deeper cognitive scheme backing it to sustain the work necessary through time.

One such deeper cognitive scheme pushing for an alternative and purposeful path out of conflict is the one that flows out of the Christian tradition of hospitality that indiscriminately invests deeply in people, pulling from wells that only God himself can fill and sustain. There are few pathways out of conflict apart from sheer exhaustion, as discussed, unless we choose it. Bretherton, commenting on various thinkers through time who struggled with the inevitability of conflict, states that “for a society to avoid being engulfed by deadly conflict, hospitality of strangers is required in order for a society to be maintained and humans to flourish.”[38] This is why Bretherton’s argument is potent. In order to have legitimate connections and a future with others who may not already be from within our own positioned view of the world, we must find a place within our self that also allows for the existence of the other as they are. This could go for communities we are a part of where we avoid generalizing and painting specific pictures of others or other groups that then prevents our legitimate engagement with them as they are. But it can also go for individuals, since we are all individually personified biographical experiences and in some ways are the end result of both positive and negative interactions with others.[39] As Christians called to love the neighbor, those negative interpretations and interactions with others should give pause as they could be shifted to actual people, re-routing the identity and biography of others from what otherwise could have been the case had openness been present.

Over 25 years ago, the influential theologian and Christian ethicist Christine Pohl wrote what is now one of the central books on Christianity and hospitality.[40] As she describes it, hospitality is not merely an industry or dinner parties but is chiefly about recognition and dignity. The recognition referred to here is that all humans are marked by the image of God, and when we do not see people as they are but with the veneer of whatever social perception filters their actual presence, we also miss or obfuscate that image. When another is in need, which could be a meal or it could merely be the shared need to be seen as a person and not an ideological position, it calls us to also reflect on our own shared and similar need. Recognizing a person with a need not only asks us to actually “see” them but the overlap extends a shared sense of humanness to those who, for whatever reason, appear quite far or separated from us. In conflict, persons want to be seen, and this need connects all of us. Their need calls to mind the same within our self, thereby connecting us. But the ability to recognize does require exposure to and interaction with those others. Afterall, the extension of dignity is not possible if it stays merely an ideal or a virtue in our mind, but it must be manifested within our real interactive worlds. To see others in the practice of hospitality strips away the possibility of power dynamics of control because in that case there is no longer a person recognized, connected with, and helped, but a case temporarily relieved.

As this implies some minimal level of relational investment or overlap, it carries with it the generous but also vulnerable sharing of oneself with the other. There is the clear challenge that agreement may never be found and conformity is unlikely, in which case Pohl argues that the other’s wellbeing cannot depend on their conformity to “us.” This links back to Kierkegaard as well. Thus, there is the historical and dual tension within the Christian practice of hospitality for people to have on the one hand, identity-defining group boundaries providing a home while, on the other hand, larger communal connections that have minimal boundaries. And this is a point that both Pohl and Bretherton make: common cultural concepts such as “tolerance” are not strong enough to stand up to this paradox that expects both the Christian’s commitment to the faith tradition while also welcoming the “stranger.”

However, this recognition or ability to perceive others has an even deeper effect on persons. The essayist and cultural/technological commentator L. M. Sacasas wrote a notable essay on hospitality that is relevant here.[41] When we love others, we will come to be connected to them as persons. This move to connect with and love others will pull us outside of our self and the community we know towards others as they are. He goes on to argue that in hospitality, “the gift we receive from the other is our own self.”[42] That is, I am who I am because I have interacted with others through time, and so the thing that each of them has given me, is me. When our relationships exist within the context of love and care, then the gift that we receive from them is a self that has been changed through the experience of that love. That self is more real than what I had, specifically because of that love. It twists me away from the wilted version of myself, breathing life into the self God intended. I become less of an abstraction, even to myself. We must be open to receive the other so as to faithfully give them their self, but also open to my self being seen and made through time as well.

Hospitality also has deep roots within the biblical narrative,[43] with the life of Christ as the high point. In the life of Christ, we see not only his willingness but preference towards engaging with those outside of what would in other circumstances be the assumed members of his group’s preferred boundaries. Christ was nearly always oriented towards those who may be an assumed deviation from his own positions, and in doing so paved the foundation for possible repaired relationships where previously only conflictual relationships were foreseeable. Or, as Bretherton says, “through his hospitality. . . . Jesus turns the world upside down.”[44] This was in part possible not because he was unsure of who he was or his own position on various topics—thus making malleable beliefs the bases upon which relationships were built—but because the confidence and clarity regarding his self allowed for engagement with those from possibly opposing positions and lifestyles.[45] And only in this way does Christ cut through all of the longstanding positions of conflict and move towards a possible future together, but also it is only in this way that people historically in conflict with a person like Jesus were able to shift their self towards the person of Jesus as well.

Connecting back to the point above regarding an increase in vulnerability and decrease in authority, we can see that Christ putting his authority aside so as to connect with people also allows those others to recognize him as a person in return. For example, in John 1:46–49, Philip goes to his friend Nathanael to tell him that he found the long-promised messiah. When Philip tells Nathanael that Jesus is from Nazareth, Nathanael automatically has an assumption about the place and the people that come from the place that disallowed him from being able to recognize Jesus as a person: “Can anything good come from there?” But when Jesus ignores this and connects with and recognizes the person of Nathanael (“How do you know me”), almost instantly Nathanael sheds his prior assumptions allowing him to recognize the person before him (“you are the son of God”).

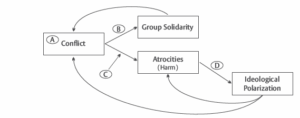

Returning to the conflict feedback loop of Collins,29 there are a few specific ways in which the Christian orientation of hospitality could shortcut the feedback and reduce amplification over time. First (see A in Figure 2), a hospitable orientation towards others does not change the fact that we will see and experience disagreement and possibly conflict because at the very least the Church should be minimally distinct from culture, but more likely in many ways strikingly distinct.30 Our orientation towards others in conflict is, or should be, one such that the Church is distinct even if this is not consistently the case.31

Second (see B in Figure 2), there is a change in what this implies for group solidarity. This conflict even within the context of hospitality likely still does produce stronger group solidarity, but hospitality would shift the rigidity of that solidarity; paradoxically distinct and separated from the other while still open to them. Some pieces of Christian community will remain closed to those the community is in conflict with, depending on the context of the conflict, such as the fact that atheists are not baptized. This in part is an affirmation of the personhood of the other as it is recognition of who they are (atheist) without twisting what some may wish they were (convert).

Figure 2. How Hospitality Could Alter the Feedback Loop of Conflict32 In this context, “atrocities” is probably not the right word as that form of violence is not as likely within relationship networks or within campus communities, but violence at least in a symbolic form is likely. When I use the term “symbolic violence” here, I have in mind the purposeful or accidental distortion of other people that alters perceptions of who they are, what they think, how they feel, or any other distortion that shifts who they are towards some alternative. This is similar to the concept of “naming” where shaping things or people also is, in a certain sense, producing the reality of them; an imposition of legitimate versions of reality.33 49This, however, is the production of a distortion, but the distortion in this case is a person. This is present in two forms. The first is a realigned relationship between conflict and what is labeled as atrocities (harm) in Figure 2 (see C). Conflict with others often necessarily flows from perceptions of those people. As our identity and view of self is at least in part dependent on our interactions with others, these perceptions of others, especially in their distorted forms, do something to or in people.[51] The only way for conflictually-distorted views of others to happen in various forms is for the disappearance of love to have taken place first.

The second form (See D in Figure 2) is that of ideological clarification, which is a further solidified imposed distortion of others. For ideological polarization to take place, we have already reduced and simplified other persons or groups of people. In other words, ideological polarization seems to require objectification of people as a pre-requisite as we come to think of them through the primary filter of the position we think they hold which then alters the actual ability to see them as a person. To simplify a person to an ideological position is also the removal of the image of God within them (them as they are, not as we make them) and the loss of love.

At the same time, it is also clearly the case that Jesus was not always loved and welcomed. This could be the inverse of the outsider’s experience of Jesus’s hospitality, where on the one hand the outsider experiences the welcome as seductively life-giving but on the other hand those who would seemingly be the insiders find that the world they knew does not actually exist in the way they thought. This jarring discovery while also doubling down on reinforcing the old boundaries creates rifts, not repairs. This means that the possibility for relational repair within the context of hospitality could require some level of mutual openness. And this makes sense, as openness to unknown possibilities is often a prerequisite for understanding. If my orientation towards others is not defined by generosity, then the likelihood of receiving them or perceiving them as they are or could be also decreases. Hospitality does not guarantee repaired outcomes, however. If I am oriented towards another generously and they are not, barriers within the interaction still exist. If nothing else, domination of another or even hermeneutical domination within an interaction precludes merging interpretive horizons.34

This is all to say, the argument for the necessity of hospitality to shortcut the feedback loops of conflict does not also require agreement or capitulation to the other. Afterall, Jesus clearly is not leaving behind his beliefs or priorities when he has conversations or dinners with some deemed outside acceptability. All this means is we must cultivate an orientation to the other that fully and legitimately allows them to be their self while at the same time also, and paradoxically so, does not overlook wrong. This means, at least in our epistemologically-bounded case, that we must be open to the possibility that we are actually wrong because it precludes a closed reading of the other. Disagreement does at some level first require understanding, but if we are not open to the other then recognition of them or understanding is not possible.[53]

While one may argue that the challenge or refusal to acknowledge those on the other side is consistent and not new, politics in the United States has entered a different era truly setting current experiences apart.35 And so, that understanding is conceivably a challenge now for both the “winner” and the “loser”, although more so for the winner. A large number of Christians voted for Trump but struggle to connect with the fear and anger that others feel, especially because much of that frustration is not rooted in policy disagreements. This is not a one-way street. Those who voted for Biden when he won struggled to connect with a shock of loss so strong that many gravitated to fabricated stories of an unreliable election. Winning, then, makes connection harder because “reality” is verified in the win. That is, the bewilderment that can come with loosing removes the choice of sensemaking—that ability to automatically veneer over irregularities in reality. When one loses, rethinking the world in which they live may no longer be optional but required. But if you win, the danger is that you feel as though your world is confirmed, further expanding the chasm between the worlds of winner and loser.

Hospitality, however, removes the comfort of a confirmed world. It looks at the rich man donating to the temple and comments that their vision for a repaired community is anemic. Are winners able to look beyond the world known to see the face of the other shockingly destabilized, scared, sad, and probably angry, so as to see the neighbor they are called to love? The relief of winning is its own threat. Are losers able to look beyond that destabilized world and see the face of the other shockingly relieved and hopeful, so as to see the neighbor they are called to love? The frustration of losing is its own threat.

So, the “gift” of a loss is the possibility of recognizing people. This is obviously not the logically necessary outcome. The conflict cycle is more likely, with rigid, ideologically produced perceptions. Hospitality rips this away. The win is more challenging because the external indication that something is amiss is absent. When the “other side” responds with shock, dismay, and sadness, it could lead to solidarity instead of curiosity. The conflict cycle is more likely, with rigid, ideologically produced perceptions.

One of the challenges behind both the response of recent “winners” and “losers” in American politics is that in conflict and solidarity we are in part seeking to reify that the world we see or want is indeed the world that is. One of the primary losses in this tendency is the flexible openness that comes with a hospitable orientation. The loss then is not an individual loss, but a communal one. Communities are not lazily possible because the effort required always had direct, personal returns on the investment. It is possible because there is enough diffused investment to sustain it; we all win in community when anonymous and unknown others invest, care, and find internal space to “host” one another. We do not all need to agree, but we do need to be able, if we love, to see one another.

Our lives are at least in part defined by the odd paradox of living in a world we can feel powerless to change or influence, but at the same time our shared daily life is built and structured by the actions, whether overtly intentional or not, of people. The question then is, do we contribute to a world we want to live in, or do we throw fuel on the fire that is burning down the house we share? With few desirable off ramps from conflict amplification and the command to love the neighbor, it may be time for Christians to recover and more deeply invest in and refine the practice of hospitality that can allow our perceptions and perspectives of others to shift towards recognition. Or as Pohl said, “in our lives, and in our churches, recovering a vision of holiness or faithfulness that is expansive and generous, gracious and truth-filled could be transformative as it is paired with a vision of hospitality that is not afraid of, or unavailable to, human brokenness.”[55]

A while back during a visit to Boston I stopped to work at the Boston Public Library. Being my first visit there, I was astonished by the pervasive beauty of a place made to house books but also could not imagine proposing to build the same today. That investment in beauty strikes us as a misuse of money, but then outside the building, inscribed in stone, it says “Founded through the munificence and public spirit of citizens.” I love that, in part because I wish we had it today—munificence: something that is lavishly generous. Hospitality provides the munificent perspective of other people that shapes them through time and is connected back to the munificent gaze of Christ who shapes us, if we can recover and engender the vision to see it.

[1].

[2]. For a very helpful description of the history that produced the background for this current cultural orientation, see James Davison Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity: On the Cultural Roots of America’s Political Crisis (Yale University Press, 2024).

[3]. Eli J. Finkel et al., “Political Sectarianism in America,” Science 370, no. 6516 (2020): 533, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1715.

[4]. Julie M. Norman and Beniamino Green, “Why Can’t We Be Friends? Untangling Conjoined Polarization in America,” Political Psychology (2025): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.13084.

[5]. Rachel Kleinfeld, Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/09/polarization-democracy-and-political-violence-in-the-united-states-what-the-research-says?lang=en.

[6]. See Randall Collins, Interaction Ritual Chains, Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology (Princeton University Press, 2004).

[7]. See, for example, Matthew 5:9.

[8]. Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Doubleday, 1966), 33.

[10]. Randall Collins, “C-Escalation and D-Escalation: A Theory of the Time-Dynamics of Conflict,” American Sociological Review 77, no. 1 (2012): 4, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411428221.

[11]. Lewis A. Coser, Functions of Social Conflict (Simon and Schuster, 1964).

[12]. These assumptions of others are what phenomenologists call “typifications” where we cast those near to us as well as those not immediately known to us as a “kind” of known person. Somewhat akin to a stereotype, but without the negative connotations as we cannot “know” a person (whether, again, an actual known person or someone distant to us and we are merely aware of their existence) without the assumptions. The primary difference is the accuracy and specificity—unknown others necessarily are given less specific assumptions and often also less accurate ones. See Berger and Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality.

[13]. Kyle Anderson et al., “How Liberal-Conservative Friendship Diversity Could Improve Interpolitical Relations in the United States,” Social Psychological and Personality Science (2025), https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506251348006.

[14]. One way this works out within American religious congregations is that as American religion, and often evangelical congregations, become less moderate and more polar over time, those who were more moderate (or neutral) feel increasingly like outsiders and leave. One the one hand, this creates a stronger and more committed core remaining, but on the other hand it creates a distillation feedback loop that has fewer opportunities to engage with possibly disconfirming relationships. See Landon Schnabel and Sean Bock, “The Persistent and Exceptional Intensity of American Religion: A Response to Recent Research,” Sociological Science 4 (November 2017): 686–700, https://doi.org/10.15195/v4.a28; Mark Chaves, American Religion: Contemporary Trends (Princeton University Press, 2011), 211.

[15]. Christian Smith, Moral, Believing Animals: Human Personhood and Culture (Oxford University Press, 2003).

[16]. Alasdair C. MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 2nd ed. (University of Notre Dame Press, 1984).

[17]. Luke Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness: Christian Witness Amid Moral Diversity, 1st edition (Routledge, 2017), 12. Here and in what follows in this section I am following Bretherton’s very helpful explanation and conversation of the arguments of both MacIntyre and O’Donovan.

[18]. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness.

[19]. Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order: An Outline for Evangelical Ethics, Revised ed. (Eerdmans, 1994).

[20]. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness.

[21]. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 67.

[23]. Eli J. Finkel et al., “Political Sectarianism in America,” Science 370, no. 6516 (2020): 533–36, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1715; Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity.

[26].

[27]. Randall Collins, Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory (Princeton University Press, 2009).

[28]. Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action.

[29]. See Mark 12:31; Luke 10:29.

[30]. Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love (Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2009).

[31]. Andy Crouch, Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk and True Flourishing (IVP Books, 2016).

[32]. Kierkegaard, Works of Love.

[33]. 2 Corinthians 8:13–15 NIV.

[34]. This is a point that sociologists have found in other situations of generosity as well. See Christian Smith and Hilary Davidson, The Paradox of Generosity: Giving We Receive, Grasping We Lose, 1st edition (Oxford University Press, 2014).

[35]. Martin Luther took one’s work in the world and vocation seriously, equating one’s faithful work to humans ‘wearing the mask of God’ as God works out his will in the world. Gustaf Wingren, Luther on Vocation (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004); Winston D. Persaud, “Luther on Vocation, by Gustaf Wingren: A Twenty-First-Century Theological-Literary Reading,” Dialog 57, no. 2 (2018): 84–90, https://doi.org/10.1111/dial.

[36]. See 1 Kings 17:8–16.

[37]. Matteo Cinelli et al., “The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 9 (2021): e2023301118, world, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118; Samuel C. Rhodes, “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation,” Political Communication 39, no. 1 (2022): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887; Robert Luzsa and Susanne Mayr, “Links Between Users’ Online Social Network Homogeneity, Ambiguity Tolerance, and Estimated Public Support for Own Opinions,” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 22, no. 5 (2019): 325–29, https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0550; Sara B. Hobolt et al., “The Polarizing Effect of Partisan Echo Chambers,” American Political Science Review 118, no. 3 (2024): 1464–79, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423001211.

[38]. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 126.

[39]. L. M. Sacasas, “The Skill of Hospitality,” in Breaking Ground: Charting Our Future in a Pandemic Year, ed. Anne Snyder and Susannah Black (Plough Publishing House, 2022).

[40]. I am following her description of hospitality for the next two paragraphs, especially chapter 4, of Christine D. Pohl, Making Room, 25th Anniversary Edition: Recovering Hospitality as a Christian Tradition (Eerdmans, 2024).

[41]. Sacasas, “The Skill of Hospitality.”

[42]. Sacasas, “The Skill of Hospitality,” 185.

[43]. MacIntyre and O’Donovan both agree that all perspectives come from within specific traditions, and so the hospitality called for here in the Christian tradition may be in some ways specific to the Christian tradition. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 127.

[44]. Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 129.

36 Instead of Jesus being concerned that engagement with those different from himself would somehow contaminate him or his beliefs, it was the exact opposite. Those others having the experience of being hosted fully by Christ allowed them to be open to him, breaking down barriers that had long been fortified by resolute boundary maintenance through time. Or, as Bretherton puts it, “Instead of sin and impurity infecting him, it seems Jesus’ purity and righteousness somehow ‘infects’ the impure, sinners and the Gentiles.” Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 130.[47]. While much has been written about the degree to which the Church should be distinct from culture, the distinction is even present within Niebuhr’s “Christ of culture” orientation that is minimally distinct from culture. There Christ is still directing enlightenment and peace, which we arguably have not attained, and so the distinction remains. H. Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture (Harper & Row, 2001).

[48]. Pre-dating and possibly even predicting the rise of Trump politics, Hunter was critical of the Church on this point, saying: “. . . contemporary Christian understandings of power and politics are a very large part of what has made contemporary Christianity in America appalling, irrelevant, and ineffective—part and parcel of the worst elements of our late-modern culture, rather than a healthy alternative to it.” James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (Oxford University Press, 2010), 95.

[52]. I find it helpful here to keep in mind the idea that meaning is on some level necessarily a communal or relational production, and this can only happen when certain communicative prerequisites are in place. See Jürgen Habermas, “On Systematically Distorted Communication,” Inquiry 13, nos. 1–4 (1970): 205–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747008601590. This also makes sense given hermeneutical theories mentioned above where understanding and meaning is present when one is open to receiving the meaning of another, but this is negated in the presence of power, domination, and control.

[53]. Here, again, I have in mind work within hermeneutical theory. For example, Ricoeur said that “to understand oneself in front of a text is quite the contrary of projecting oneself and one’s own beliefs and prejudices; it is to let the world and its world enlarge the horizon of the understanding which I have of myself.” Paul Ricoeur, Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences: Essays on Language, Action, and Interpretation, with John B. Thompson (Cambridge University Press, 1981), 178. Here, I am understanding the other person as the text to be read, and to understand them also means that my understanding of myself has expanded as a response to making “room” for them, so to speak. For an expanded description of conceptualizing people as a text to be read, see Aaron B. Franzen and Deborah Vriend Van Duinen, “Reading Beyond Words: People as Texts to Be Literate In,” The Bell Tower 4, no. 1 (2025), https://blogs.hope.edu/belltower/bell-tower-volume-4-issue-1/reading-beyond-words-people-as-texts-to-be-literate-in/.

[54]. See especially part IV of Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity. We no longer have debates about what our shared world could or should look like. The option that feels inevitable is that of domination even if it means total loss along the way. For example, Hunter says, “What we have, rather, is a simulacrum of public moral debate that has come to conceal a raw and brutalizing competing will to power.” Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity, 313.

[55]. Pohl, Making Room, 204.

Munificent Selves: Hospitality

as an End to Conflict Amplification

Aaron B. Franzen

When I look into the face of my enemy

I see my brother, I see my brother

Forgiveness is the garment of our courage

The power to make the peace we long to know

Open up our eyes

To see the wounds that bind all of humankind

May our shutter hearts

Greet the dawn of life with charity and love[1]

We recently finished up another election season, and for some that went quite well and for others it went quite badly. Some of my students were struggling with the outcome of the election, even to the point of tears, and I kept thinking about how otherworldly and nonsensical that response may be to many others. I wanted to at least bring it up in class to check in with them and see whether they wanted to talk about the outcome. Initially, nearly none of them wanted to talk about it. I told them that it seemed as though it was fairly contentious and that things were unlikely to get better if we remain unable to talk about it. I wanted to take a moment to think through the social processes of that experience.

Students described how conflictual conversations had been and how the vast majority of those conversations were situations where they did not feel as though the conversation partner was even hearing what they were trying to say. Others described a delicate dance where they would slowly feel out the other person to see if a conversation was possible or not. It seemed as though this was another instance of only being able to have a conversation if the other was at least somewhat already in agreement. These conversations and interactions with students about the recent election and my own attempts to make sense of relational conflict became the seeds for the present article.

Over the last few years, many people feel there has been an overall increase in conflict, often having roots in politics.[2] For example, on the common temperature scale (warmth reflects positive affect while lower temperatures reflect negative associations or perceptions), ratings of one’s own party have remained consistently warm since the 1980s, while perception of the opposing political party has decreased from about 48 degrees (neutral) to about 20 degrees in 2020.[3] This tends to preclude relationships and interactions with others.[4] Much of this conflict is affective in nature and not over the contents of policy per se,[5] but for the purposes of communal conflict this distinction likely does not matter. A large proportion of our interactions are driven by a preconscious emotional attraction or repulsion, and so this affective orientation that is either positive or negative is influential.[6] What I am interested in here is not larger, macro-level conflicts, but the conflict within existing relationships, families, campuses, or other communities where individuals do have the actual opportunity for interaction with others. The problem is that there is a natural feedback loop for conflict that makes it quite challenging to avoid amplification. This poses a real challenge for Christians who are called to be peace makers.[7] While there are many examples of the munificent and lavishly generous possibility of people towards one another, conflict can also cause us to fold in upon our selves in a penurious manner; avoiding this possibility must be purposeful.

Here, I give an overview of how feedback loops of conflict function, then highlight how it is challenging to see a path forward within the context of moral diversity in the modern world. I then propose that an orientation of generosity and hospitality may be a way forward. My main interest here is that if people are the end result of a chain of historical interactions that shape any given identity, overt conflict or conflict in the background of interactions will shift people away from what they could have been in the context of a flourishing relationship into what they have become as a result of conflictual interactions through time.

The Process and Feedback Loop of Conflict

While it is possible for conflict to devolve into overt violence, the conflict I have in mind here generally takes on a more benign and stable form instead of physical violence. For example, a college campus community can be characterized by conflictual relations between students with violence never overtly taking place. On the other hand, the absence of conflict does not imply the absence of disagreement, which is often an unrealistic expectation even within the context of committed friendships. The primary difference between the possibility of disagreement within relationships as opposed to conflict is when there is an increase in interest and investment in the other person that shifts them from an interchangeable abstract person into a person in the specific and known.[8] It is unlikely one can “know” someone in the absence of some degree of intimacy that personifies the other. When there is an increase in intimacy, the other can be known to a degree that makes their position sensical instead of nonsensical, even if still rejected in the end. Conflict, at least the more intractable kind described below, is to a greater or lesser degree dependent on the objectification of the other, keeping them as they are or imagined to be at a distance. In other words, it is the absence of the commitment to see and continually rediscover a person and then proceed with the interaction or social process accordingly.

The sociologist Randall Collins, who has written several articles and two books on violence, formalized pre-existent but somewhat unsystematic social theories explaining how conflict works within social groups.37

Conflict within social groups tends to have an inherent feedback loop that amplifies the conflict across time (see Figure 1). This is because real or perceived conflict tends to clarify social group boundaries, driving people back to affinity groups, which in turn tends to further clarify and increase the initial conflict. Additionally, that conflict can, over time and once it reaches certain generally emotional thresholds, lead to atrocities (atrocities in his model are in reference to wider-spread group or identity-driven violence). While Collins’s main interest is in how and when violence breaks out, the same can apply in the absence of actual physical violence with threats, gossiping, slander, or other seemingly benign forms of action against another individual or group. As this begins to happen, not only is the initiator’s group identity and boundary clarified but they also come to solidify perceptions of the opposition. As this “violence” moves towards solidified perceptions of the other group, it tends to, again, feed back into and amplify the original perception of conflict.

Figure 1. The Feedback Loop of Conflict[10]

There is a certain positive and even necessary role for conflict within society as it tends to resolve tensions within groups and relationships and push people to avoid developmental stagnation. This could have the effect of an increased sense of belonging within a group.[11] That is, if “we” are unified in our opposition to some other group, then it can have the effect of strengthening our bond with one another. The cost is that this increased sense of solidarity with one another can have the effect of pushing us into further conflict as the contents of the conflict come to be clarified and more in focus.

The challenge within a community is that it is all perceptual. We rarely verify that the assumptions we have built up about other people or groups are accurate—if they reflect what they actually think or who they are. People merely progress with perceptions and assumptions being “taken for granted” unless something forcibly removes the assumptions from us.[12] This might be a situation where we are no longer able to overlook the incongruence between our assumptions of the world and others, breaking some piece of our “reality” or breaking some perception of the world around us and the people in it. There is the possibility that we come to increasingly perceive those around us through an ideological lens that acts as the filter for our perceptions. This has the tendency to push us further yet into increased conflict. Our taken-for-granted knowledge of others around us becomes, by and large, stable, leading us to avoid interactions with those we already “know” about. This is unlikely to change without unavoidable disconfirming interactions with others outside of something artificial that forces interaction, like a structured psychological study.[13]

This conflict does not need to result in physical or overt public actions being taken against others. While obviously possible, much of this conflict remains in the background, mainly finding its home in the affective and emotional orientation of some against others. What I have in mind is somewhat subtle conflict that can come off as passive aggressive or sarcastic interactions, sheer avoidance, or other micro indications that friction exists, although it could also become more overt at times. I say this because this is the conflict that likely exists within congregations, workplaces, schools, families, or loose friend groups. This complicates these communities with the natural feedback loop, making it worse. It is possible that none of these relationships have this kind of conflict and exist within a context of homogeneity, but this is likely the result of complete conflict feedback loops that have already pushed out the neutrals, or those who do not strongly associate their self with one “side” or the other, so as to increase the sense of solidarity within the defined group.[14]

The Complication of Moral Diversity

On the one hand, we could hope for a future that is less ideological and conflictual because we can work towards an agreement regarding what things are “good” and what kind of world we should work towards. This, however, is dramatically unlikely because there is no real way to objectively verify whether one perspective or interpretation of a moral good is indeed better or more desirable than another.[15] Claims to objective knowledge necessarily come from within a pre-existing narrative creating coherence. So, one can form claims within any given perspective, yes, but between perspectives this is not the case. This does not, to be clear, mean that there are not ontologically real things, merely that all perceptions of those things are necessarily situated from within some pre-existing structure that gives it coherence, complicating an “objective” adjudication of the claims.

One of the notable challenges about perceptions regarding what we as individuals and collectives should do is that for the most part those perspectives have come to be detached from meaning systems, and are no longer, in the phraseology of the influential moral theorist Alasdair MacIntyre, teleologically driven.[16] This is a problem for MacIntyre because there is no longer the same shared basis upon which we can answer questions regarding what it is that we should do.[17] Because our ability to process the world around us and be rational are “inherently tradition-bound” and contextualized, and because there are increased social and contextual fractures in these moral backgrounds, there is also an increase in the conflict regarding moral visions.[18] And at times this is violent, a point I will return to in a moment.

While MacIntyre leaves us feeling quite skeptical regarding the possibility of reclaiming a shared moral vision for the future, the Anglican priest and ethicist Oliver O’Donovan offers a modified alternative.[19] For O’Donovan, the world as it is ontologically does not come to be conflated with what we know about the world epistemologically, which allows him to make claims regarding a right moral vision for the world even though our specific contexts may alter or distort our ability to know or enact that vision.[20] We cannot have a view from nowhere, and this leads us to have a vison of the “moral” that is also more or less clear. For this reason, cultural location and context are still important because we are all enacting the stories we find our selves within, even if there is still only a single reality within which those embodied contexts perceive the world. Hence, for O’Donovan, this is the place of repentance and forgiveness: “that is, it is the Spirit which enables humans to respond subjectively to the objective, created order of things which was restored and vindicated by Jesus Christ in his resurrection. The proper form this pattern takes is love. . . . It is the task of Christian ethics, guided by the Spirit, to trace, participate in and so bear witness to this ordering of love.”[21]

And yet in the midst of an increasingly fractured moral world it can be hard to see past those contextualized perceptions of the world that then shape moral visions of the world. This is especially the case as the groups shaping those perceptions may come to be increasingly smaller, with fewer overlaps, a consequence Durkheim pointed out as a possibility of the modern division of labor.38 As groups come to be increasingly specialized and autonomous, they come to have fewer connections with those dissimilar to their selves. Societies are stable to the degree that they have a shared perception of the world they share, but groups insulated from each other tend to have fewer shared perceptions. This is the place of our present interactions regarding modern American politics.[23]

An additional and possibly more helpful way to think about this comes from the sociologist G. H. Mead. Mead argued that our perceptions take on significance as any given situation becomes what it is to us as we filter through various possible symbolic interpretations of the situation, and then select the interpretation that seems most fitting.39 The problem is that one can only select from known symbolic interpretations, as they are not really produced on the spot, unless of course there is some dearth of meaning that requires some transposed and repackaged symbolic interpretation to make sense of things. All this to say, interpretive isolation will cause problems in social groups as various situations come to be increasingly meaningless to others. As conflict is the subject of this article, “situation” here is in reference to other persons or groups. It is people or groups of people that come to be increasingly meaningless in contexts of interpretive isolation.

Possible Ways Out of Conflict

Collins does specify a number of ways conflict may fail to escalate.[25] First, it is possible that people just come to avoid the conflictual group, which would then shortcut the feedback loop of conflict escalation. This possibility of avoidance is important because it is likely a common occurrence within a bounded community, like a workplace or college campus. Ironically this may just allow the conflict to fester as isolation from one another complicates the possibilities for overlaps in interpretive horizons, just making the ‘other’ more nonsensical.40 The second way that conflict can de-escalate is from the reality that there is a fairly high natural reticence for overt violence that then leaves those in conflict in dead-end feints of escalation that de-escalates from sheer boredom.[27] This is, however, probably less prominent within the types of communal conflict of interest here. Third is that the conflictual group could run out of resources thereby ending prolonged conflict. This is possible but may primarily be in reference to others’ willingness to indulge someone or a group for a period in grievance claims. Sooner or later that social or political capital comes to be spent.

The fourth possibility for de-escalation relates to the emotional burden of conflict. Because it takes an emotional investment to engage in conflict, it is possible that people or groups can come to feel burnt out emotionally—tired of the effort or the fight—which would then shortcut and end the escalation feedback loop. This emotional burnout may be the most potent source of de-escalation, and Collins posits that in most cases there is a natural half-life in measurable time whereby this happens in the sense that the ability to maintain heightened negative emotions producing the affective side of conflict is hard to maintain and dies off. I think that this pathway is likely in the communal cases of interest here, but conflictual relations may outlast this half-life because while people may not engage in overt and outright conflict, they likely still, 1) feel the oppositional orientation towards others and 2) may avoid those others as posited in the first point. Both would have a lingering effect within a bounded community that would in totality sap communal vitality. Finally, and related to the prior, part of the solidarity building process is to pull in and build alliances with others, and those alliances could fall apart for various reasons. The fracturing of alliances is likely also viable, but at least in part due to the emotional burnout or exhaustion mentioned above.

For the most part, it is possible there never is an escalation or de-escalation of the conflict and it is merely sustained at a point of equilibrium, like that elephant in the room we continue to ignore. This is the case for most of the avenues just mentioned. The main problem with any of these forms of de-escalation or with equilibrium is that the possibility of a repaired relationship is at best incidental. They are all more or less different versions of failed conflict with stable negative affect, not reconciled relationships. For the most part the natural feedback loop and amplification of conflict primarily end with exhaustion, not repair—exhaustion of resources, emotions, energy, interest, and investment.