Editor’s Note: Due to a technical issue with WordPress, this essay was published earlier this month without the text, only the tables. We have reposted the corrected version today.

Human culture and consciousness in the Global North have evolved profoundly over the past two millennia, and are conventionally referenced as the overlapping respective eras of pre-modernity, modernity, and postmodernity. However, a fourth form of modernity has arisen in the last few decades in reaction to both modernity and postmodernity. Dutch cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker articulated the first academic definition of metamodernism, describing it as both a “structure of feeling” and a pendulum which “oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity.”1 Comparing the respective eras further, Luke Turner writes that,

Whereas postmodernism was characterised by deconstruction, irony, pastiche, relativism, nihilism, and the rejection of grand narratives, the discourse surrounding metamodernism engages with the resurgence of sincerity, hope, romanticism, affect, and the potential for grand narratives and universal truths, whilst not forfeiting all that we’ve learnt from postmodernism. Thus, rather than simply signalling a return to naïve modernist ideological positions, metamodernism considers that our era is characterised by an oscillation between aspects of both modernism and postmodernism. We see this manifest as a kind of informed naivete, a pragmatic idealism, a moderate fanaticism, oscillating between sincerity and irony, deconstruction and construction, apathy and affect, attempting to attain some sort of transcendent position, as if such a thing were within our grasp.2

In seeking a transcendent position, the emergent metamodern era is itself aligned with another “post” era, that of post-secularity, which is the current return of religion to the public sphere after being stringently sequestered to the private realm by both modernity and postmodernity.3 More specifically,

post-secular societies are neither religious nor secular, they do not prescribe or privilege a religion, but neither do they actively and intentionally refrain from doing so. They are neither for nor against religion(s). … For them, religion has ceased to be something to which a society or a state has to relate in embracing, rejecting, prescribing, negating, or allowing it, … and hence there is no need for them to be secular anymore.4

Significantly, metamodernism and post-secularity have together brought spirituality back into broader interdisciplinary conversations after both modernism and postmodernism had dismissed it for different reasons.5 Brendan Graham Dempsey, author of the 7-volume Metamodern Spirituality Series and, most recently, Metamodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Cultural Logics,6 is perhaps the leading proponent of metamodern Christianity. “Drawing on the insights of all the previous cultural paradigms, the revelation of God’s nature and the deepening quality of the relationship between God and man can be understood as progressing through a series of covenants/dispensations that map to a learning process unfolding through time.”7 Similarly, in exploring “the potential to reclaim faith in Christ in a contemporary, intellectually responsible way,” philosopher Matthew David Segall states that

Ultimately, I’d hope that a metamodern approach to Christianity can transcend binaries—between history and eternity, Jesus and the cosmic Christ, and between religions themselves. Such an approach would also be able to integrate scientific and religious wisdom, recognizing that both are necessary for a comprehensive understanding of reality. After all, science, in its devotion to truth, is itself a variant form of religious pursuit grounded in metaphysical assumptions about the intelligibility and unity of nature.8

Notably, there are also strong affinities between metamodern Christianity and the “constructively postmodern” Christian process theology developed by John B. Cobb, Jr. and David Ray Griffin. “Metamodern Christians recognize that the Jesus of history isn’t identical to the Christ of faith, and they acknowledge the evolving meaning of Jesus.”9

Given the evolution of culture and consciousness in the Global North to this point in history – presumably little more could be done with the term “modern” in the future – and the impact of respective historical eras on Christianity, what metamodernism requires is a corresponding post-disciplinary meta-theoretical perspective of knowledge, that is, a theory about theory. Not so coincidentally, and perhaps divinely, that is precisely what the critical realist corrective to both modernism and postmodernism provides. First articulated by English philosopher of science Roy Bhaskar as “transcendent realism,”10 critical realism has risen to prominence recently. (For a critical evaluation of critical realism, see Tong Zhang.11)

Critical realism is built on Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant’s distinction in Critique of Pure Reason (1781) between noumena – ultimate reality that exists independent of our perception – and phenomena – objects and events we experience through our senses as shaped by our cognition. As the study of social phenomena, the social sciences have been divided between those who do so from two starkly contrasting assumptions of knowing. Empirical positivism assumes that factual knowledge comes only from things that can be experienced with the senses or proved by logic. Contrarily, social constructionism, as eminently explicated and elucidated by sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann,12 assumes that humans construct knowledge through their intelligence, experiences, and interactions with the world in a subjective search for meaning. Social scientific positivism is a child of the modern natural sciences, whereas social constructionism is an older sibling of postmodern perceptions. Additional features can be summarized as follows:

| Ontology | Empirical Positivism | Social Constructionism |

| Epistemology | Objectivism | Interpretivism |

| Reality is… | External, stable, ordered, patterned, preexisting | Internal, fluid, socially constructed, multiple, emergent |

| Knowledge is… | Objective, measurable, value-free, universal, decontextualized | Subjective, indeterminate, value rich, particular, contextualized |

| Aim | Exclamation, prediction | Description, understanding |

However, critical realism is a third, middle ground between empirical positivism and social constructionism, and consists of three pillars. It maintains that

much of reality exists and operates independently of our human awareness of it (ontological realism), that our human knowledge about reality is always historically and socially situated and conceptually mediated (epistemic perspectivalism), and that it is nonetheless possible for humans over time to improve their knowledge about reality, to adjudicate rival accounts, and so to make justified truth claims about what is real and how it works (judgmental rationality). All three of these beliefs must go together to promote the acquisition of human knowledge.13

Most significantly, critical realism also posits three levels of reality; reality is not flat. Pictured as three concentric circles, the “real” is the largest, outer, all-inclusive circle, comprised of all the material, non-material, and social “mechanisms” that exist, whether humans are aware of them or not, each mechanism having its own structures and causal capacities. The “actual” is the middle circle, comprised of all the mechanisms that have been activated, producing events in time and space, whether observed by humans or not. The “empirical” is the smallest, inner circle, comprised of all the mechanisms that have been both activated and observed, the domain of our direct or indirect phenomenological experience of the real or actual. Therefore, “what we observe (the empirical) is not identical to all that happens (the actual), and neither is identical to that which is (the real). The three must not be conflated.”14

Critical realists also differentiate between the intransitive, which is the object of knowledge as it is, and the transitive, which is our theories about the intransitive object and how we go about studying it, producing fallible social constructions that change over time while the intransitive object remains unchanged. New Testament scholar N. T. Wright is representative of relevant Christian scholarship when he explains that critical realism

is a way of describing the process of “knowing” that acknowledges the reality of the thing known, as something other than the knower (hence ‘realism’), while fully acknowledging that the only access we have to this reality lies along the spiraling path of appropriate dialogue or conversation between the knower and the thing known (hence ‘critical’).”15

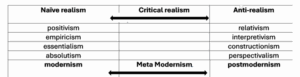

The meta-theoretical perspective of critical realism thus corrects the two polar opposite meta-theoretical perspectives that have characterized the social sciences. Modern, positivistic, naïve realism arrogantly maintains that its knowledge of reality is direct, complete, final, and universal. Postmodern, constructivist anti-realism skeptically maintains that there is no necessary correspondence between perception and reality, and that all knowledge is relative. But metamodern critical realism humbly maintains that all knowledge of reality is indirect, partial, and revisable, that much of reality exists independent from human awareness of it, and that absolute Truth exists, but is evasive, and the best humans can do is gain one perspective of it.

The resonance of critical realism with metamodern Christianity is clearly evident in their mutual ontology, epistemology, and normativity, the latter collapsing the untenable dichotomy of fact and value, of the descriptive is and the prescriptive ought.16And what critical realism obviously not only allows but suggests is the whole realm of the spiritual, including the Christian mystical “cloud of unknowing.”17 We humans long for transcendence, and intuit something more, something real beyond the empirical, and something which is not merely socially constructed. As such, spirituality is conceivably a real mechanism with its own causal capacities that exists independent from human awareness of it. When it is activated, or perhaps because it is constantly activated, it is also actual, producing events in time and space, whether observed by humans or not. When it is sensed by humans through direct or indirect experience, it also becomes empirical and to that extent knowable and known. Spirituality presumably, and by definition, takes us beyond both empirical positivism and social constructionism, that is, beyond social science itself.

Acknowledgement: This blog post is a condensation and adaptation of the editorial in the Fall 2025 issue of the Journal of Sociology and Christianity (Vol. 15, No. 2).

Footnotes

- Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, “Notes on Metamodernism,” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 2, no. 1 (2010).

- Turner, Luke. 2015. “Metamodernism: A Brief Introduction.” Metamodernism: A Brief Introduction – Notes on Metamodernism

- Christoffel Lombaard, Iain T. Benson, and Eckart Otto, “Faith, Society and the Post-Secular: Private and Public Religion in Law and Theology,” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75, no. 3 (2019).

- Ingolf U. Dalferth, “Post-secular Society: Christianity and the Dialectics of the Secular,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 78, no. 2 (2010): 317.

- Dave Vliegenthart, “The Meaning of Metamodern Spirituality: Beyond Modern and Postmodern Perspectives on the Religious and the Secular,” Journal of Contemporary Religion 40, no. 1 (2025). See also A. Severan, Metamodernism and the Return of Transcendence (Palimpsest Press, 2021)

- Brendan Graham Dempsey, Metamodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Cultural Logics (ARC Press, 2023).

-

- Brendan Graham Dempsey, Metamodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Cultural Logics (ARC Press, 2023).

- Matthew David Segall, “What is Metamodern Christianity?” 2024. What is Metamodern Christianity? – Footnotes2Plato

- Jay McDaniel, “Christian Process Theology and Metamodernism: Springboards for Conversation.” Christian Process Theology and Metamodernism: Springboards for Conversation – Open Horizons

- Roy Bhaskar, A Realist Theory of Science (Verso, 1975); and Roy Bhaskar, The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Science (Humanities, 1979).

- Tong Zhang, “Critical Realism: A Critical Evaluation,” Social Epistemology 37, no. 1 (2023).

- Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Penguin Books, 1966).

- Christian Smith, Religion: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Matters (Princeton University Press, 2017), 9.

- Christian Smith, What is a Person? Rethinking Humanity, Social Life, and the Moral Good from the Person Up (University of Chicago Press, 2010), 93.

- N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God: Christian Origins and the Question of God (Fortress Press, 2004), 35.

- Brad Vermurlen, “Sociology, Christianity, and Critical Realism,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Sociology and Christianity, ed. Dennis Hiebert (Routledge, 2024).

- The Cloud of Unknowing with the Book of Privy Counsel, trans. Carmen Acevedo Butcher (Shambhala, 2009).